Multi-objective optimization by quantum annealing (2511.01762v1)

Abstract: An important task in multi-objective optimization is generating the Pareto front -- the set of all Pareto-optimal compromises among multiple objective functions applied to the same set of variables. Since this task can be computationally intensive even for small problems, it is a natural target for quantum optimization. Indeed, this problem was recently approached using the quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA) on an IBM gate-model processor. Here we compare these QAOA results with quantum annealing on the same two input problems, using the same methodology. We find that quantum annealing vastly outperforms not just QAOA run on the IBM processor, but all classical and quantum methods analyzed in the previous study. On the harder problem, quantum annealing improves upon the best known Pareto front. This small study reinforces the promise of quantum annealing in multi-objective optimization.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What this paper is about

This paper studies a tough kind of problem called multi-objective optimization. That’s when you try to do well on several goals at the same time, even if improving one goal might make another worse. The best trade-offs form what’s called the Pareto front: a set of “no-regrets” choices where you can’t improve one goal without hurting another.

The paper compares two quantum computing methods for building this Pareto front:

- QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm), used in a previous paper on an IBM quantum computer and in idealized simulations.

- Quantum annealing, run on a D-Wave quantum annealer.

The big message: for the same test problems and the same overall approach, quantum annealing was much faster and found better trade-offs.

Key questions the researchers asked

- If we swap QAOA for quantum annealing in the exact same workflow, does it find the Pareto front faster or better?

- Can quantum annealing beat not just real QAOA hardware and idealized QAOA simulations, but also strong classical (non-quantum) methods?

- On a harder test (with four goals), can quantum annealing improve the best-known Pareto front?

How they did it, in simple terms

Think of each solution as a plan scored on several goals (like cost, speed, quality). A plan is Pareto-optimal if you can’t make one goal better without making at least one other worse.

To build the Pareto front, the workflow does this:

- Mix the goals into a single score using random weights (like saying “60% importance on goal A, 30% on B, 10% on C”). Do this many times with different weights.

- For each set of weights, ask the quantum machine to find high-scoring solutions (lots of samples).

- Collect all solutions and keep only the non-dominated ones—the plans that are not clearly worse than any other.

- Measure progress using hypervolume, which is like the “area/volume covered” by your set of non-dominated points. Bigger hypervolume means a better, more complete Pareto front.

What problems did they test?

- A graph-cut problem (maximum cut), which can be written in the “Ising model” form that quantum machines like to solve. You can think of it as splitting a network into two sides to maximize the total weight of edges cut.

- Two versions: one with 3 goals and one with 4 goals, both on a 42-node graph with randomly chosen edge weights.

What’s QAOA vs quantum annealing?

- QAOA: a gate-based quantum algorithm that applies a sequence of quantum “steps” (here, 6 layers) and then measures. It was tried both on an IBM device and in a perfect (noise-free) simulator.

- Quantum annealing: starts with a very “wiggly” quantum system and slowly turns down the wiggles so it settles into a good solution. The authors ran this on D-Wave hardware.

Helpful details about the runs (kept simple):

- QAOA (from the earlier paper): used 5,000 samples per weighting for 3 goals, and 20,000 samples per weighting for 4 goals, either on real IBM hardware or in a noise-free simulator.

- Quantum annealing (this paper): used only 1,000 samples per weighting, but could do many weightings in parallel on the D-Wave chip. Each batch took about 0.2 seconds to return a huge number of samples (tens of thousands).

What’s “hypervolume”?

- Imagine plotting all your solutions on a graph with one axis per goal. The hypervolume is how much space is covered by the non-dominated solutions relative to a “worse-than-all” reference point. The larger the hypervolume, the better your coverage of the Pareto front.

Main findings and why they matter

Here are the key results, explained plainly:

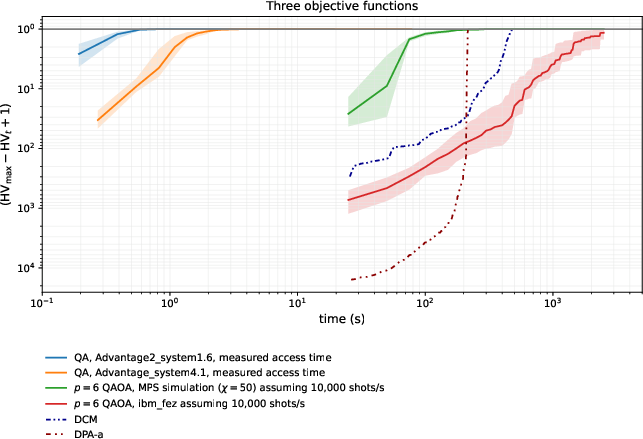

- Three-goal problem:

- Quantum annealing reached the optimal Pareto front (2,067 non-dominated solutions) very quickly—often in under 2 seconds of machine time.

- It was over 100 times faster than the idealized, noise-free QAOA simulator (assuming a generous sample rate for that simulator), and roughly 1,000 times faster than QAOA run on the IBM device, which didn’t reach the optimum in the reported runs.

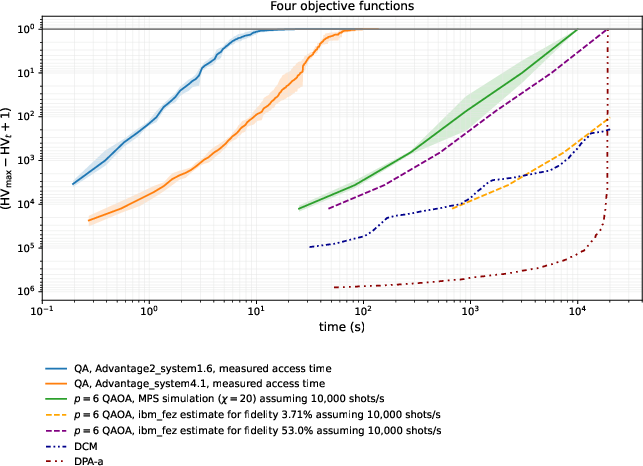

- Four-goal problem (harder):

- Quantum annealing found a better Pareto front than all other methods tested, discovering 30,419 non-dominated solutions—beating the previous best of 30,409.

- It reached the best front in far fewer samples and less time than the idealized QAOA simulator (again, assuming generous sampling rates for that simulator).

- Classical methods tested in the earlier paper did not reach this best front, partly because they used a simplified (discretized) version of the numbers.

Why this matters:

- The Pareto front is the gold standard for multi-goal decision-making. Finding it faster and more completely means better decision support in the real world.

- On current hardware, quantum annealing appears much more practical than QAOA for this kind of task.

What this could mean going forward

- For problems where you need the best trade-offs across several goals—think logistics, engineering design, scheduling, or finance—quantum annealing could deliver strong results quickly on today’s machines.

- While QAOA has attractive theory for future fault-tolerant quantum computers, this paper adds to growing evidence that, right now, quantum annealing is often the better tool for large batches of high-quality solutions in combinatorial optimization.

- The paper shows a simple, repeatable recipe: replace QAOA with quantum annealing in a standard Pareto-front-building workflow and you may get big speedups, better fronts, or both.

In short: If you’re trying to balance many goals at once, this paper suggests that quantum annealing is a powerful, practical way to find the best trade-offs with today’s technology.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of unresolved issues and concrete directions that would enable rigorous follow-up studies:

- Limited benchmark scope: Only two synthetic instances (N=42 heavy-hex graphs with independent Gaussian edge weights) and M∈{3,4}. Test across larger N, diverse graph families (dense/sparse, random/structured), correlated objectives, real-world instances, and higher M (≥5).

- No certified optimality for the four-objective case: “Believed optimal” Pareto front (30,419 points) lacks proof. Provide certificates via exact multi-objective ILP/CP (e.g., ε-constraint enumeration), exact bounds on HV, or complete dominance verification for tractable subproblems.

- Weighted-sum scalarization only: This method can miss unsupported (non-convex) Pareto-optimal points. Evaluate alternative scalarizations (Chebyshev/augmented Chebyshev, achievement scalarizing functions) and ε-constraint formulations mapped to Ising penalties to guarantee coverage of the entire front.

- Weight-vector sampling strategy: Uniform random draw over the simplex is not sample-efficient. Compare against space-filling/deterministic designs (simplex-lattice, Sobol/Halton sequences), adaptive refinement based on uncovered regions of the front, and multi-armed allocation between “more c’s” vs “more shots per c”.

- End-to-end runtime fairness: QA timings include QPU program/readout; QAOA/MPS use assumed shot rates; HV computation time excluded. Report full wall-clock for all methods (including HV computation, pre/post-processing, and realistic queue/latency) and calibrate MPS/QAOA throughput on actual hardware.

- Missing classical baselines for continuous weights: Compare against state-of-the-art multi-objective methods without discretization (NSGA-II/III, MOEA/D, SMS-EMOA, MO-CMA-ES, Pareto Local Search, ε-constraint ILP/CP, simulated annealing/tabu/LNS variants) and quantify solution quality/time.

- No comparison to classical annealing or quantum-inspired solvers: Include simulated annealing, parallel tempering, simulated quantum annealing, tensor-network samplers, and specialized Ising accelerators (e.g., DAU/CMOS annealers).

- Scalability of sample complexity: No analysis of how shots, weight vectors, and total QPU calls scale with N, M, or target HV gap. Derive empirical scaling laws and stopping criteria for a given HV tolerance.

- Parallel packing dependence: Results leverage packing 96–114 disjoint copies. Quantify throughput and performance when only a single (larger or embedded) instance fits, and when graph-minor embeddings introduce overhead and noise.

- Hardware parameter sensitivity untested: Only 1 μs anneals, default schedules, no spin-reversal (gauge) averaging, no anneal pauses/quench, and no reverse annealing. Characterize performance vs schedule shape, anneal time, pauses, reverse annealing, gauges, and error mitigation.

- Sample diversity and correlation: Diversity of QA samples (e.g., Hamming distance, effective sample size) and its effect on Pareto coverage are not measured. Assess and enhance diversity via gauge cycling, parameter dithering, or lightweight post-processing (local search).

- Hypervolume (HV) computation bottleneck: HV for 30k+ points in 4D may dominate host runtime as N, M grow. Report HV compute times and evaluate scalable alternatives (incremental/approximate HV algorithms, dominance filtering on-device/streaming).

- Objective scaling and reference point: HV depends on objective scales and the reference point. Analyze robustness to scaling/normalization and compare alternative reference points; ensure fair cross-instance comparisons.

- Applicability beyond unconstrained binary max-cut: Extend to constrained MOO, mixed/bounded integer variables, and non-binary encodings; paper penalty tuning, feasibility recovery, and QA performance under constraints.

- Mechanistic understanding: The paper does not explain why QA outperforms QAOA. Investigate spectral gap proxies, freeze-out dynamics, landscape structure, diabatic transitions, and how these affect Pareto coverage and diversity.

- Sensitivity to analog control errors: Auto-scaling used, but impacts of coefficient magnitude, coupler range, control errors, and calibration drift were not studied. Quantify robustness and the benefits of spin-reversal averaging and error mitigation.

- QAOA baseline underexplored: Uses p=6 from prior work; no exploration of deeper circuits, alternative mixers (e.g., problem-informed), optimizer strategies, improved transpilation, dynamical decoupling, or error mitigation. Re-benchmark with optimized QAOA to ensure fairness.

- Higher-dimensional Pareto fronts: Only M=3,4 evaluated. Study feasibility, coverage, and computational burden (HV and non-dominated sorting) for M>4, and evaluate scalarizations and indicators better suited to many objectives.

- Budget attribution across methods: The number of weight vectors and shots per vector differ between approaches. Provide ablations that equalize total samples, shots-per-c, and number-of-c vectors to disentangle their contributions to HV.

- Throughput generality: QA performance depends on device-specific readout times and batching. Report sensitivity to hardware generation, readout settings, batching limits, and mixed workloads.

- Reproducibility and uncertainty: Provide confidence intervals for HV, dominance counts, and times; analyze variability across many random seeds/instances; perform hypothesis tests to substantiate superiority claims.

Glossary

- Advantage2_system1.6: A specific D-Wave Advantage2 quantum annealing system used as the solver. "Using the {Advantage2_system1.6} solver, we can pack 96 disjoint copies of into the qubit connectivity graph"

- Advantage_system4.1: A previous-generation D-Wave Advantage quantum annealing system variant. "we also present data from the previous-generation Advantage_system4.1 solver, which is noisier but can sample from $114$ vectors in parallel"

- anneal: A single execution of an annealing schedule that evolves the quantum state to minimize energy. "We run anneals of duration $\SI{1}{\micro s}$"

- bond dimension χ: The parameter controlling the expressiveness and computational cost of MPS simulations. "bond dimension ( is used to tune the tradeoff between computational resources and sample quality)"

- DCM: A classical algorithm for multi-objective optimization using discretized weights. "Also included for comparison are two fully classical algorithms, DCM and DPA-a"

- DPA-a: A classical multi-objective optimization algorithm operating on discretized weights. "Also included for comparison are two fully classical algorithms, DCM and DPA-a"

- duty cycle: The fraction of time a processor spends actively executing versus overhead like readout. "meaning that the overall duty cycle of the QA processor is dominated by readout time"

- fault-tolerant QPU: A quantum processing unit capable of error-corrected operation allowing theoretical guarantees. "QAOA, which has theoretical approximation guarantees in an ideal fault-tolerant QPU"

- gate-model processor: A quantum computer that operates via discrete quantum gates rather than annealing. "on an IBM gate-model processor"

- Hamiltonian: The energy function (operator) defining the dynamics and objective of a quantum system. "mixer Hamiltonians and objective Hamiltonians are alternatingly applied to a quantum state"

- heavy-hex qubit connectivity graph: IBM’s qubit layout topology with heavy-hexagonal connectivity. "the heavy-hex qubit connectivity graph of IBM quantum processors fits into that of D-Wave quantum annealing processors as a subgraph"

- heavy-hex spin glasses: Spin-glass problems mapped onto heavy-hex connectivity graphs. "this was previously shown to be effective in heavy-hex spin glasses"

- hypervolume (HV): A metric for the quality of a set of Pareto-optimal points measuring dominated volume relative to a reference. "we use the hypervolume (HV) of non-dominated points as a figure of merit"

- ibm_fez: A specific IBM quantum processor used for QAOA experiments. "actual QAOA experiments using the ibm_fez processor"

- Ising optimization problem: An optimization formulation using binary spins with pairwise couplings. "Weighted maximum-cut can be expressed as an Ising optimization problem"

- matrix-product-state (MPS): A tensor-network representation used to simulate quantum circuits efficiently. "noise-free matrix-product-state (MPS) simulations of QAOA could outperform classical approaches"

- mixer Hamiltonian: The Hamiltonian in QAOA that drives exploration of the state space between objective applications. "multiple layers (in this study, ) of mixer Hamiltonians and objective Hamiltonians are alternatingly applied to a quantum state"

- multi-objective optimization (MOO): Optimization involving simultaneous trade-offs among multiple objectives. "In multi-objective optimization (MOO), one must simultaneously consider the priorities of multiple stakeholders"

- non-dominated points: Solutions that are not strictly worse in all objectives compared to any other solution. "QA found a better Pareto front than all other approaches, consisting of 30,419 non-dominated points"

- objective Hamiltonian: The Hamiltonian encoding the classical objective function to be minimized or maximized. "multiple layers (in this study, ) of mixer Hamiltonians and objective Hamiltonians are alternatingly applied to a quantum state"

- Pareto front: The set of trade-off solutions where improving one objective worsens another. "with the Pareto front made up of 2067 non-dominated points"

- Pareto-optimal: A solution where no objective can be improved without degrading at least one other. "the set of all Pareto-optimal compromises among multiple objective functions"

- QPU: Quantum Processing Unit, the hardware executing quantum computations. "We report total QPU access time, including programming and readout"

- qubit connectivity graph: The graph describing which qubits are directly coupled on a quantum device. "we can pack 96 disjoint copies of into the qubit connectivity graph"

- quantum annealing (QA): A quantum optimization method that slowly reduces quantum fluctuations to reach low-energy states. "The second is quantum annealing (QA)"

- quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA): A gate-based variational algorithm alternating between mixer and objective Hamiltonians. "The first is the quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA)"

- quantum fluctuations: Random quantum deviations that can help explore the energy landscape during annealing. "in which quantum fluctuations are attenuated"

- quantum phase transition: A transition between quantum states induced by changing parameters like the Hamiltonian. "guiding an initial state through a quantum phase transition"

- spin-reversal transformations: Techniques that flip spin assignments to reduce bias and enhance energy scaling on annealers. "do not use spin-reversal transformations to further boost the energy scale"

- weighted maximum-cut: A graph optimization problem maximizing cut weight with edge weights. "A recent study of QAOA applied to multi-objective weighted maximum-cut problems"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are practical, deployable applications that leverage the paper’s workflow and findings—particularly the demonstrated speed and quality advantages of quantum annealing (QA) for generating Pareto fronts in multi-objective, unconstrained binary optimization (Ising/QUBO). Each bullet notes sector relevance, potential tools/workflows, and key dependencies.

- Replace QAOA-based pipelines with QA for Pareto front generation in multi-objective binary problems

- Sectors: software, operations research, academia

- Tools/workflows: D-Wave Ocean SDK; the paper’s open-source code for random scalarization and parallel embeddings; moocore for hypervolume computation

- Why now: QA produced near-optimal Pareto fronts in seconds (e.g., 2067 points for 3-objectives; 30,419 points for 4-objectives) with a >100–1000× speedup over QAOA baselines

- Dependencies/assumptions: Access to D-Wave hardware via cloud (Leap); problem fits native connectivity; Ising formulation; hypervolume computation cost manageable

- Rapid decision support for multi-criteria network partitioning and segmentation

- Sectors: cybersecurity (zero-trust segmentation), telecommunications, enterprise IT

- Tools/workflows: Weighted max-cut formulations on real networks; random convex weight sweep; 96-way parallel sampling; interactive dashboard for Pareto navigation

- Why now: Heavy-hex topologies embed directly; 96 parallel instances were shown feasible, enabling sub-2s turnarounds for moderate-size graphs

- Dependencies/assumptions: Binary encoding of goals; handling constraints via penalties; privacy controls for cloud QPU use

- Circuit and system partitioning for EDA with multi-objective trade-offs (cut size, timing, power)

- Sectors: semiconductors, VLSI/EDA

- Tools/workflows: Multi-objective max-cut on netlists; automated anneal schedule with auto-scaling of couplers; post-Pareto selection by designers

- Dependencies/assumptions: Quality of embedding and penalty calibration for constraints; mapping fidelity to real physical metrics

- Multi-objective community detection and market segmentation

- Sectors: marketing/CRM, social network analysis

- Tools/workflows: Graph partitioning maximizing multiple criteria (e.g., modularity, demographic alignment, churn risk); QA-based Pareto front exploration

- Dependencies/assumptions: Suitability of max-cut proxies for domain metrics; interpretability of solutions for non-technical stakeholders

- Benchmarking and calibration of classical MOO solvers using high-quality Pareto fronts

- Sectors: software optimization, academic research

- Tools/workflows: Use QA fronts as ground truth to tune heuristic parameters (e.g., DCM/DPA-a), validate hypervolume improvements

- Dependencies/assumptions: Comparable problem formulations; reproducibility via shared code/data

- Interactive policy analysis for districting and planning with multiple fairness/compactness criteria

- Sectors: public policy, urban planning

- Tools/workflows: Weighted max-cut for region partitioning; QA front generation; stakeholder workshops to explore compromise solutions

- Dependencies/assumptions: Legal and ethical constraints encoded as penalties; transparent objective design

- Real-time scenario exploration in operations (what-if analyses)

- Sectors: logistics, manufacturing

- Tools/workflows: Fast sampling of Pareto compromises under changing weights (cost, emissions, service level); dashboards with hypervolume tracking

- Dependencies/assumptions: Problems map to binary variables; integration with operational data streams; compute budgets for repeated sampling

- Teaching and lab exercises on multi-objective optimization

- Sectors: education, academia

- Tools/workflows: Use the paper’s code to demonstrate Pareto fronts, hypervolume, random scalarization strategies; compare QA, QAOA, classical baselines

- Dependencies/assumptions: Classroom access to cloud QPUs or recorded datasets; moocore installation and usage

Long-Term Applications

These opportunities require further research, scaling, improved hardware/software, and broader integration. Each bullet highlights sector relevance, potential product/workflows, and critical dependencies.

- Enterprise-scale multi-objective resource allocation and scheduling

- Sectors: cloud/IT operations, manufacturing, transportation

- Tools/products: “Quantum Pareto Front Generator” integrated into planning suites; continuous re-optimization as data updates

- Dependencies/assumptions: Larger problem sizes with constraints; robust penalty strategies; improved connectivity and embedding efficiency on QA hardware; faster readout and anneal schedule tuning

- Financial portfolio optimization balancing return, risk, liquidity, and ESG

- Sectors: finance

- Tools/products: QA-driven Pareto front explorer for portfolios; compliance-aware objective design; interactive weight sliders

- Dependencies/assumptions: Accurate QUBO mapping for constraints (e.g., cardinality, transaction costs); scalability to hundreds–thousands of assets; rigorous backtesting and regulatory acceptance

- Multi-objective grid control and network reconfiguration (loss, reliability, resilience)

- Sectors: energy/utilities

- Tools/products: QA-enabled decision-support for line switching, microgrid islanding; real-time Pareto updates under contingencies

- Dependencies/assumptions: High-fidelity power system models to binary encodings; integration with SCADA/EMS; low-latency, on-prem or secure cloud QA access

- Robotics and autonomous systems: real-time path and task planning with safety, energy, and latency trade-offs

- Sectors: robotics, autonomous vehicles

- Tools/products: Onboard or edge QA copilot for multi-objective plan selection; dynamic weight adjustment under situational changes

- Dependencies/assumptions: Millisecond-level inference needs; specialized hardware or accelerated access; deterministic safety guarantees; robust mapping from continuous to binary objectives

- Drug discovery and materials design: co-optimizing potency, toxicity, synthesizability, and stability

- Sectors: healthcare, pharma, materials science

- Tools/products: QA-assisted multi-objective screening; Pareto front filtering integrated with generative models and lab automation

- Dependencies/assumptions: Scalable encoding of complex property predictors into QUBO; large search spaces; data-driven penalty calibration; validation pipelines

- Large-scale supply chain network design (cost, time, resilience, emissions)

- Sectors: logistics, retail, manufacturing

- Tools/products: QA-backed orchestration for multi-objective network partition/flow planning; scenario stress-testing

- Dependencies/assumptions: Mixed-integer constraints require careful embeddings/penalties; cross-enterprise data sharing; scalability to thousands of variables

- Fairness-aware AI model selection and hyperparameter tuning

- Sectors: software/ML, governance

- Tools/products: Pareto explorer for accuracy, fairness metrics, compute cost; governance dashboards to select acceptable compromises

- Dependencies/assumptions: Mapping of hyperparameter spaces to binary variables; integration with training loops; generalization guarantees

- City-scale districting and infrastructure planning with multi-objective guarantees

- Sectors: public policy, civil engineering

- Tools/products: QA-as-a-service for public engagement; visualization of Pareto fronts for transparent decision-making

- Dependencies/assumptions: Larger graph instances; stakeholder-defined objective functions; legal compliance; explainability tooling

- General-purpose “ParetoFront-as-a-Service” platform

- Sectors: cross-sector

- Tools/products: Cloud API that wraps D-Wave QA, random scalarization, parallel embeddings, and hypervolume computation; visualization and export

- Dependencies/assumptions: Cost-effective QPU access; robust autoscaling of couplings; optional spin-reversal transformations; hardened privacy/security

Notes on feasibility and assumptions, grounded in the paper’s methods and results:

- Problem form: Best suited to unconstrained binary (Ising/QUBO) problems or problems where constraints can be reliably represented with penalties; penalties require calibration.

- Hardware access and performance: Demonstrated gains rely on D-Wave Advantage2_system1.6; sample quality and speed depend on anneal schedule, readout time (~0.2s per 1000-shot call yielding 96,000–114,000 samples), and embedding overhead.

- Workflow specifics: Random convex scalarization across objectives; 96-way parallel embeddings; moocore algorithm for hypervolume and non-dominated filtering; auto-scaling of couplers to J∈[−2,1]; spin-reversal transformations (not used in the paper but known to help) may further improve energy scales.

- Coverage and optimality: Random weights approximate the full Pareto front; completeness depends on sampling breadth and quality; hypervolume computation becomes costly for very large fronts.

- Comparative claims: Reported speedups are relative to the studied QAOA baselines (including MPS simulations at assumed shot rates and IBM ibm_fez experiments); future gate-model hardware advances could change this balance.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.