Learning Linearity in Audio Consistency Autoencoders via Implicit Regularization (2510.23530v1)

Abstract: Audio autoencoders learn useful, compressed audio representations, but their non-linear latent spaces prevent intuitive algebraic manipulation such as mixing or scaling. We introduce a simple training methodology to induce linearity in a high-compression Consistency Autoencoder (CAE) by using data augmentation, thereby inducing homogeneity (equivariance to scalar gain) and additivity (the decoder preserves addition) without altering the model's architecture or loss function. When trained with our method, the CAE exhibits linear behavior in both the encoder and decoder while preserving reconstruction fidelity. We test the practical utility of our learned space on music source composition and separation via simple latent arithmetic. This work presents a straightforward technique for constructing structured latent spaces, enabling more intuitive and efficient audio processing.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about teaching a special kind of AI “audio compressor” to behave in a simple, predictable way. The goal is to make its hidden code (called the “latent space”) act like regular math so that turning the volume up or down and mixing sounds together can be done by easy arithmetic on that code. This makes audio editing faster, clearer, and more efficient.

Key Questions

The authors set out to answer a few straightforward questions:

- Can we make a compressed audio “code” behave linearly, so that:

- Scaling the code scales the sound (like a volume knob)?

- Adding codes adds the sounds (like mixing two tracks)?

- Can we do this without changing the model’s design or adding complicated new loss functions?

- Can we keep audio quality high while gaining this “linear” behavior?

- Is the new space useful for real tasks, like mixing and separating instruments?

Methods and How They Work

What’s an autoencoder?

Think of an autoencoder as a shrink-and-expand machine for audio:

- The encoder compresses the audio into a short “recipe card” (the latent code).

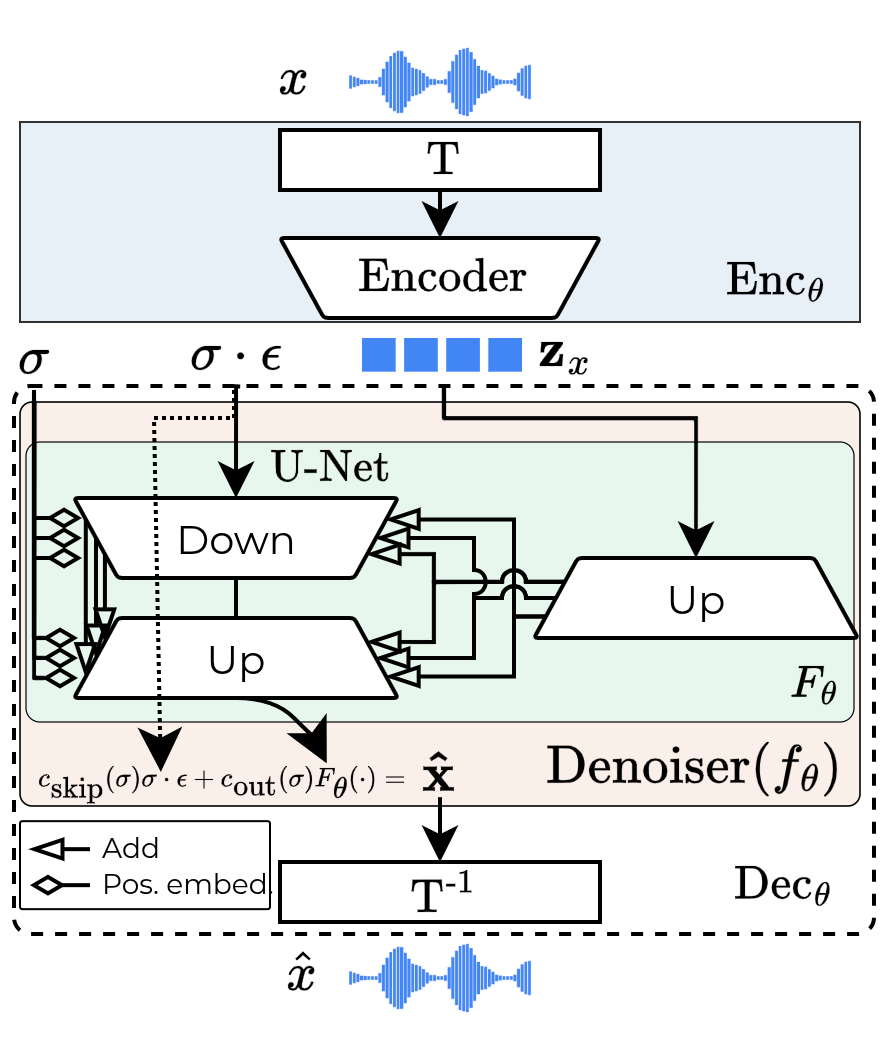

- The decoder uses that recipe to rebuild the original audio.

A Consistency Autoencoder (CAE) is a type of autoencoder where the decoder is built from a “consistency model,” which can reconstruct clean audio in one fast step, even if it starts from noisy input. That makes decoding quick and high quality.

What does “linear” mean here?

Linearity means two simple rules:

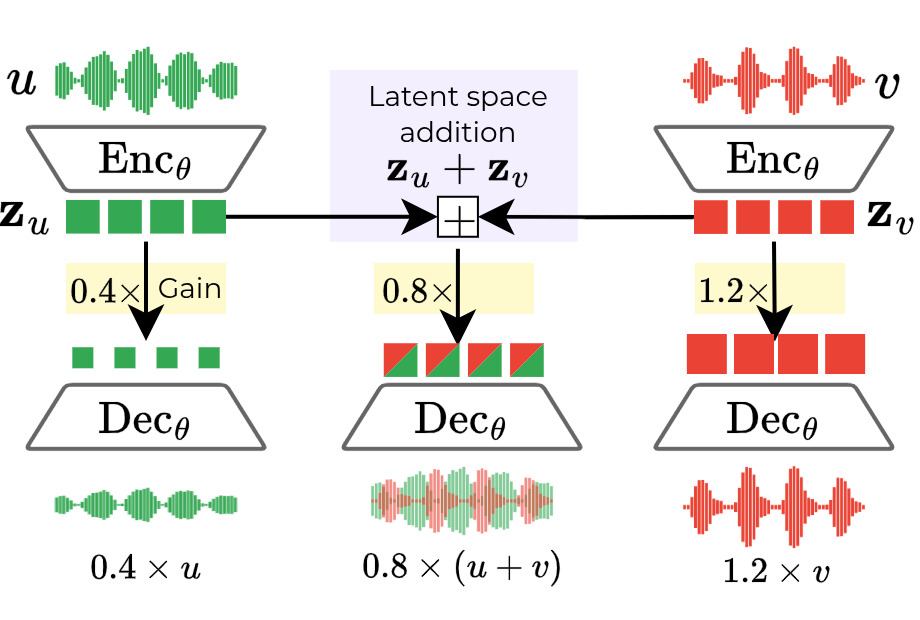

- Homogeneity: If you multiply the code by a number (say 0.5 or 2), the output sound gets quieter or louder by the same amount.

- Additivity: If you add the code for sound A to the code for sound B, the decoder outputs A+B (a proper mix), not something weird.

The training trick (implicit regularization)

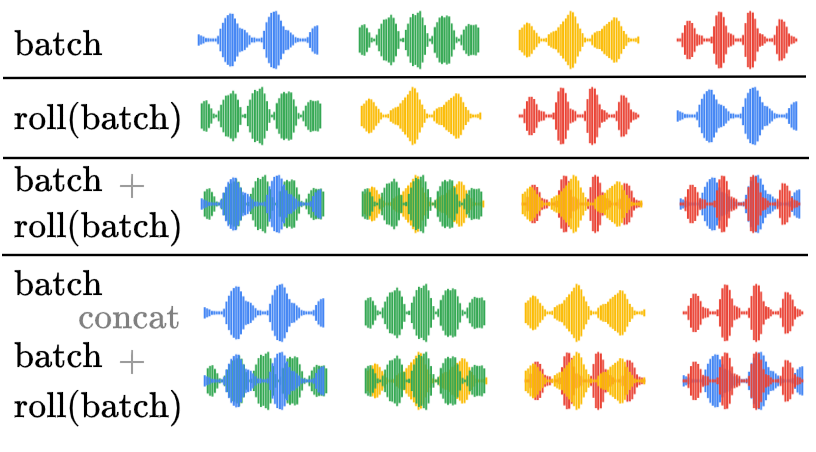

Instead of changing the model’s design, the authors use clever data augmentation during training so the model learns these rules naturally:

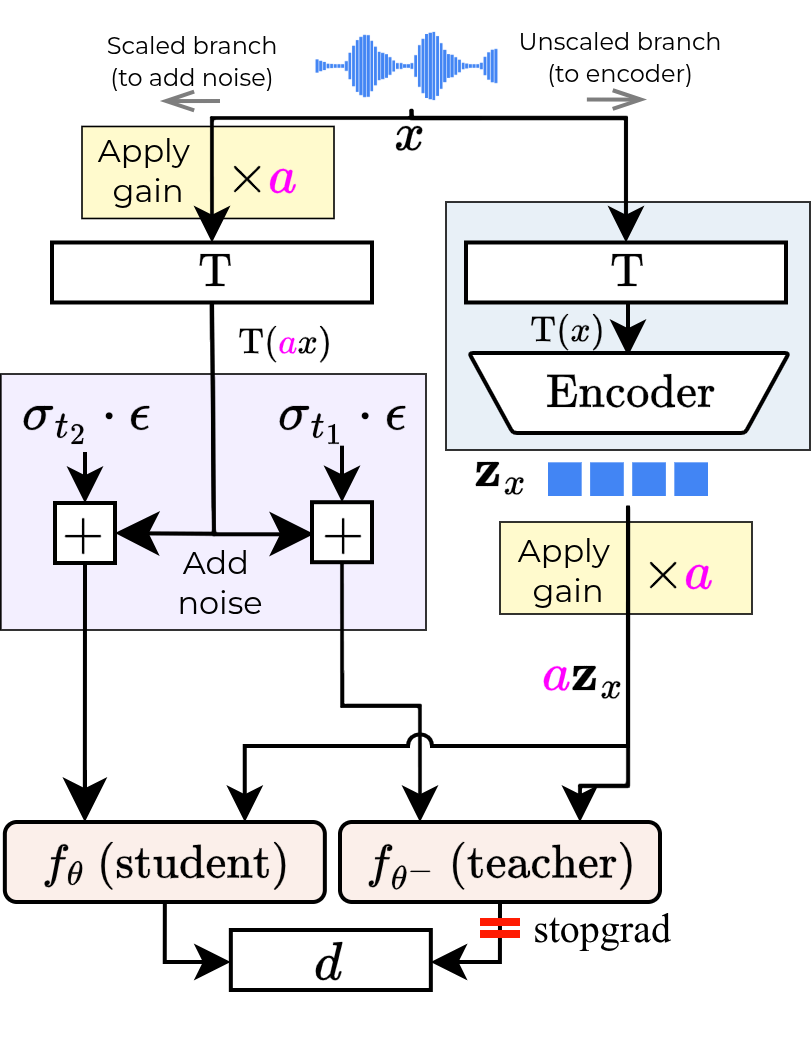

- Homogeneity: They randomly apply a volume change (gain) to the latent code and ask the decoder to produce audio at that same new volume. The gain value itself isn’t given to the model; it has to “figure out” the right loudness from the magnitude of the code. This trains the decoder to connect code size to output volume.

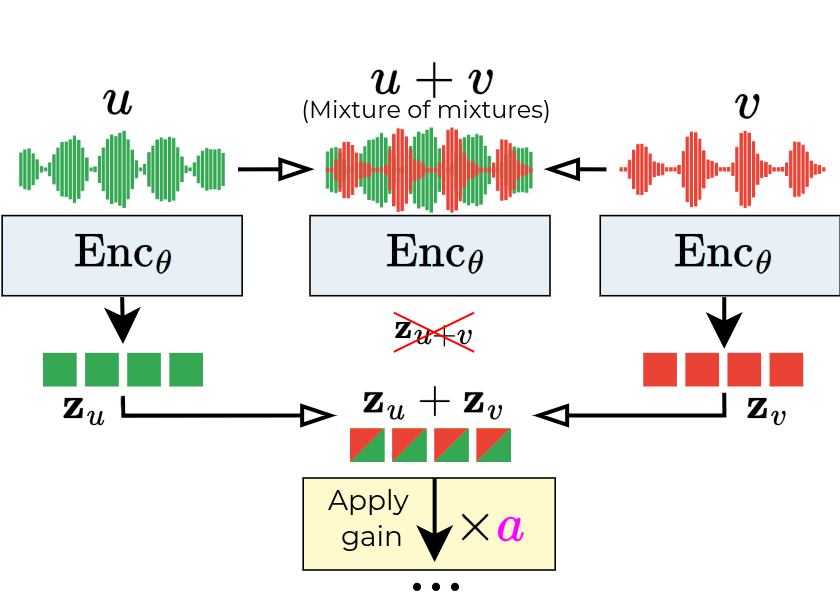

- Additivity: They make artificial mixes by summing two different audio clips. Then, instead of encoding the mix directly, they encode each clip separately and add their codes. The decoder is asked to reconstruct the mix from this summed code. This trains the decoder to treat addition in code space as true mixing in audio space.

Behind the scenes, they use a “teacher–student” consistency training setup: two versions of the decoder try to agree on how to clean up noisy inputs at different noise levels. You can think of it like a coach (teacher) and a player (student) who practice on the same sounds with different amounts of static; the player learns to match the coach’s cleaned-up result. This keeps reconstructions sharp and stable.

Main Findings

Here are the main outcomes the authors report:

- The latent space becomes approximately linear:

- Scaling the latent code scales the output sound correctly.

- Adding codes produces clean mixes that closely match the original mixtures.

- This works not only in the decoder but also shows up in the encoder: the encoder’s outputs scale and add in expected ways, which makes the whole system easier to understand.

- Audio quality is preserved: the “linearized” CAE keeps reconstruction fidelity similar to strong baselines.

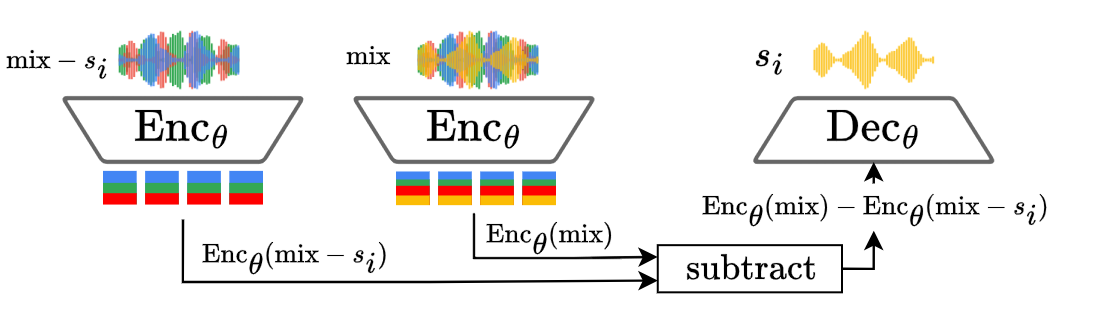

- It beats other models on mixing and source separation via simple code arithmetic:

- For example, to isolate vocals, you can subtract the code of “everything but vocals” from the code of the full mix and decode the result. The method performs better than popular baselines on this kind of “oracle” separation.

- Ablation tests (turning off one training trick at a time) show both homogeneity and additivity matter, with homogeneity giving a surprisingly big boost to additivity as a side effect.

In short, the model learns to treat simple math in the compressed space like real volume control and mixing, and does so without sacrificing sound quality.

Why This Matters

This research makes audio editing and processing more efficient:

- Faster workflow: You can mix, scale, and separate audio directly in the compressed code, avoiding repeated full encodes/decodes.

- Clearer control: Because the space is linear, it’s more predictable—turning up the code really turns up the sound, and adding codes really adds sounds.

- Strong foundation: A structured, linear latent space can make downstream tasks (like music generation, style transfer, or instrument separation) simpler and more reliable.

- Easy to adopt: The method doesn’t require changing the model’s design or loss—just smart training augmentation—so it can be applied to other autoencoders.

Overall, this is a simple, powerful way to make compressed audio representations behave more like everyday math, opening the door to cleaner, faster, and more intuitive audio tools.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following points identify what is missing, uncertain, or left unexplored, with concrete directions for future work:

- Model-agnostic generalization: The method is claimed to be architecture-agnostic but is only validated on a Music2Latent-style CAE. Test on diverse autoencoder families (e.g., waveform decoders, VAEs, Neural Audio Codecs/VQ, multi‑step DiffAEs) to assess whether linearity emerges consistently.

- Theoretical guarantees: Provide formal analysis or bounds on “approximate linearity” (e.g., homogeneity/additivity error as a function of gain, noise level, and training schedule) and conditions under which encoder linearity arises despite only decoder-targeted augmentation.

- Negative and out-of-range gains: Training uses only positive gains and clips large amplitudes. Systematically paper behavior under negative gains, very small gains, and gains beyond the range to map failure modes and define safe operating regions.

- Number and composition of sources: Additivity training uses two-source artificial mixes and evaluation uses four-source MUSDB mixtures. Analyze sensitivity to the number of sources, source balance (unequal gains), and source diversity, including more than four sources.

- Mixture realism and distribution shift: Artificial mixes are built by circularly shifting and summing random tracks. Compare against more realistic mixing protocols (e.g., genre-balanced, instrument-aware, dynamic-range-aware, reverberant or compressed mixtures) and quantify the impact on learned linearity.

- Dependence on the STFT amplitude transform: Linearity is enforced in the presence of a specific complex STFT with a non-linear amplitude scaling (). Evaluate whether linearity holds with raw waveform, alternative spectral representations (log-magnitude, mel, CQT), or different amplitude scalings.

- Training schedule sensitivity: The homogeneity gain range is annealed to no gain near the end of training. Explore schedule variations (no anneal, slower/faster decay, different application probabilities, curriculum over gains) and quantify how they affect linearity and reconstruction.

- Clipping side effects: Gains are clipped to keep waveforms within , introducing non-linear targets. Measure how often clipping occurs and whether it degrades homogeneity/additivity; consider alternative normalization strategies to avoid target distortion.

- Encoder linearity mechanism: The encoder exhibits improved homogeneity/additivity without explicit encoder losses. Investigate why and under what conditions encoder linearity emerges, and whether adding small explicit encoder constraints further improves performance.

- Long-duration, streaming, and boundary effects: Experiments use 2-second mono chunks with overlap-add. Test continuity and linearity over longer durations, streaming scenarios, and stereo/multi-channel audio to evaluate practical deployment.

- Reconstruction–linearity trade-offs: Quantify trade-offs between linearity and perceptual quality (rate–distortion–perception) with more perceptual metrics (FAD, human listening tests) and examine whether stronger linearity compromises fine timbral detail or transients.

- Evaluation against original sources: Separation quality is measured against autoencoded sources (not original ground truth), conflating AE reconstruction error with separation. Re-evaluate against original sources to isolate true separation performance.

- Downstream generative tasks: Assess whether linearized latents benefit text-to-music generation, style transfer, controllable editing, or diffusion sampling quality, and whether linearity impedes or enhances generative diversity.

- Calibration of latent magnitudes: The method implicitly encodes amplitude in latent norm. Study normalization/calibration schemes (e.g., latent scaling factors, per-channel normalization) to improve numerical stability and interpretability of latent arithmetic.

- Internal feature linearity: Current metrics test I/O linearity. Probe intermediate U-Net layers and upsampling blocks to assess where linearity is enforced or broken, guiding architectural tweaks for stronger linear behavior.

- Robustness to audio chain non-linearities: Real mixes often include compression, saturation, and non-linear effects. Test how learned linearity behaves when inputs include such processing and whether additional augmentations are needed.

- Fair baseline comparisons: SA‑VAE and M2L-Pub differ in data, objectives, and training regimes. Retrain these baselines with identical datasets and apply the proposed linearization method to them to assess true method generality and fairness.

- Additivity ablations depth: Beyond “only homogeneity”/“only additivity,” explore mixture creation variants (random source counts, gain ratios, genre-conditional mixing), and quantify their differential impact on additivity and separation.

- Noise schedule and loss choice: Linearity may interact with CT time-step schedules and the Pseudo‑Huber loss. Perform sensitivity analyses for different noise schedules, loss functions, and CT variants (e.g., EDM, iCT tweaks) to find optimal settings.

- Frequency-dependent homogeneity: Examine whether homogeneity holds uniformly across frequency bands and dynamics (e.g., bass vs. cymbals). Use band-wise or time-frequency localized metrics to identify where scaling is most/least accurate.

- Efficiency claims benchmarking: The paper claims efficiency benefits from latent arithmetic. Provide measured encoding/decoding speed-ups, memory savings, and end-to-end pipeline benchmarks versus operating in waveform space.

- Generalization across domains: Validate on speech-only, environmental sound, and highly percussive/transient datasets, including multilingual speech and out-of-domain genres, to establish robustness and limits of the learned linearity.

- Multi-channel and spatial processing: Extend and evaluate the method for stereo/multichannel audio and spatial mixing operations (e.g., pan, rotation), and explore linear equivariances to spatial transforms in the latent space.

- Interaction with discrete/token latents: Investigate whether implicit linearity can be induced in discrete-codec latents (VQ or transformer tokenizers), and how arithmetic would map back to token sequences without harming codebook utilization.

- Extreme compression regimes: The model uses compression. Test lower and higher compression factors to characterize how compression strength affects achievable linearity and downstream task performance.

- Metrics for linearity: Develop standardized metrics for homogeneity/additivity (e.g., Lipschitz-like constants, gain error curves, source-count sweep charts) to enable rigorous, comparable evaluation across models and datasets.

Practical Applications

Below is an overview of practical applications that follow from the paper’s core idea: an audio autoencoder whose latent space is approximately linear (homogeneous and additive) via simple, model-agnostic training-time data augmentation. The approach preserves high-fidelity reconstruction with high compression and single-step decoding, enabling intuitive audio manipulation through latent arithmetic (scaling and mixing).

Immediate Applications

These are deployable now or with minor engineering, leveraging the released code and weights and the demonstrated performance on music and speech.

- Creative software and DAWs (software, media/entertainment)

- Applications: Latent-domain mixing and gain control (e.g., adjust stem levels, create mixes, batch normalize loudness) without repeated encode/decode; faster offline rendering of large session edits.

- Tools/products/workflows: A “Linear Latent Codec” DAW plugin; an SDK exposing Enc/Dec/scale/add for host apps; batch processors for catalog editing.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model weights available; 44.1 kHz audio; GPU or optimized inference for real-time; acceptable reconstruction/HQ demands; licensing for integration with commercial tools.

- Streaming/catalog operations (media/entertainment, cloud software)

- Applications: Latent-domain loudness normalization, playlist crossfades, auditioning stems or variations at scale with reduced compute; internal catalog preprocessing and A/B testing of mixes.

- Tools/products/workflows: Cloud microservices that store latents and perform scale/add, returning previews; automated pipelines for catalog conditioning (gain/mix).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain alignment with training data; server-side GPU or efficient CPU inference; consistent sample-rate/transforms; rights management for stem handling.

- Game/VR runtime audio (software, gaming)

- Applications: Runtime mix control of compressed stems (e.g., environment music intensity scaling, crossfading layers) via latent arithmetic with single-step decoding.

- Tools/products/workflows: Unity/Unreal engine module for latent mixing; asset pipeline storing latents instead of full waveforms; simple gain curves controlling soundtrack intensity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real-time feasibility on target hardware; domain-specific fine-tuning (game audio); memory footprint; audio quality trade-offs acceptable in context.

- Audio post-production and podcasting (media/entertainment)

- Applications: Latent-domain loudness normalization, sidechain/ducking via scalable gain, quick composite mixes for dialogue, music beds, and SFX.

- Tools/products/workflows: Post-production batch tools that compress assets, apply latent gain/mix, and decode once; scripting pipelines for editors.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Alignment with loudness standards (e.g., EBU R128) after decoding; monitoring for timbral stability under scaling; workflow validation.

- Research and education (academia)

- Applications: New benchmarks and metrics for encoder/decoder linearity (homogeneity/additivity); controlled mixture creation in latent space for experiments; reproducible demos for signal processing pedagogy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Open notebooks demonstrating Enc/Dec, scale/add metrics; curriculum materials on linear operations and diffusion-CAE decoding; dataset augmentation pipelines using latent arithmetic.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to GPUs; faithful reproduction of training schedules; alignment with research datasets.

- Speech analytics and telephony workflows (software, telecommunications)

- Applications: Latent-domain gain control for multi-speaker recordings; scalable mixing of channels (e.g., agent vs. customer tracks) in compressed form for downstream NLP/ASR pipelines.

- Tools/products/workflows: Call-center preprocessing services that compress streams and apply gain/mix before ASR; analytics systems that handle large-scale audio more efficiently.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Speech-focused training/fine-tuning; regulatory compliance for audio processing; robustness across telephony codecs.

- Archival and collaboration (media/entertainment, software)

- Applications: Efficient stem storage and collaborative mixing in latent form; quick offline bounces from latent for review/notes.

- Tools/products/workflows: Version-controlled latent repositories; collaborative “latent mixboards” for remote teams.

- Assumptions/dependencies: IP/licensing for stems; storage policies for latent artifacts; consistency guarantees across versions of models.

Long-Term Applications

These need further research, scaling, standardization, or productization beyond the paper’s current scope.

- Personalized streaming and client-side remixing (media/entertainment, software)

- Applications: Deliver content in latent form and enable end-users to adjust stem levels (e.g., emphasize vocals, lower drums) or generate personalized mixes client-side.

- Tools/products/workflows: Streaming APIs serving latents; client decoders integrated with UI sliders for stem intensity; per-user preference profiles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: On-device inference performance (mobile/TV); industry licensing and rights management for stems; standardization of latent formats; security measures to prevent unauthorized reconstruction/sharing.

- Latent-domain source separation without stems (software, research)

- Applications: Train companion estimators to predict component latents from a mix, enabling practical source separation via latent arithmetic for arbitrary music.

- Tools/products/workflows: Separation models that output latent components; pipelines that subtract/add latents to isolate sources; datasets constructed with latent composability constraints.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust additivity under real-world mixtures; dataset availability with reliable labels; evaluation standards; generalization across genres.

- Generative audio editing and controllable music production (media/entertainment, software)

- Applications: Integrate linear latents with text-to-audio systems to adjust intensity, instrument balance, and blend sources by algebraic operations on latents; “compositional” generative workflows.

- Tools/products/workflows: Generative model stacks that tokenize/encode into linear latents; creative UIs for parametric control; plugin ecosystems around latent controllers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Joint training with generative models; user experience designs; consistent decoding fidelity; compute cost management.

- Edge/IoT audio processing and energy-efficient pipelines (software, energy/embedded)

- Applications: On-device compression, gain adjustments, and mixing for wearables, smart speakers, and AR devices to reduce bandwidth and CPU cycles.

- Tools/products/workflows: Quantized/accelerated decoders (e.g., mobile NN accelerators); latent caching for repeated operations; lightweight codecs with linear latents.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model pruning and quantization; platform-specific acceleration; robustness to non-stationary acoustics; battery/thermal constraints.

- Privacy-preserving audio analytics (policy, software)

- Applications: Share/process latents rather than raw audio to reduce direct content exposure while enabling gain/mix operations; audit trails limiting reconstruction.

- Tools/products/workflows: Privacy-preserving latent formats; controlled decoding policies; secure enclaves for reconstruction; watermarking in latent domain.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Risk assessment (invertibility implies reconstructability); legal frameworks for derivative representations; adoption by compliance stakeholders.

- Standards, licensing, and rights management for latent audio (policy, industry standards)

- Applications: Define interchange standards for linear latents; develop licensing and royalty models for personalized remixes and stem-level controls.

- Tools/products/workflows: Industry working groups (e.g., standards bodies) defining formats and rights; licensing middleware tracking latent manipulations.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; compatibility with existing content distribution ecosystems; enforceable digital contracts.

- Clinical and assistive speech tools (healthcare)

- Applications: Controlled loudness normalization and source emphasis (e.g., patient voice vs. ambient noise) using latent arithmetic in clinical recordings or hearing-assist apps.

- Tools/products/workflows: Therapy apps supporting latent-level adjustments; pre-processing in telehealth platforms; auditory training tools.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Clinical validation and safety; training on pathological speech datasets; integration with medical data practices and regulations.

- Scalable education platforms and interactive learning (education, software)

- Applications: Web apps that teach linearity, mixing, loudness, and signal processing via interactive latent operations; large-scale classroom adoption.

- Tools/products/workflows: Browser-based demo environments; curricula and labs on latent arithmetic; integration into MOOCs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Efficient server/client inference; accessible datasets; institutional adoption.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Linearity is “approximate,” with demonstrated robustness but still domain-dependent.

- Training used positive gains; negative gains (subtractive operations) worked in tests but may need explicit training for broader robustness.

- Reconstruction quality is strong but may trail two-stage adversarial codecs for certain production needs; application-specific QA is advised.

- Real-time constraints depend on decoder efficiency; single-step decoding helps, but hardware optimization and quantization will be important for edge scenarios.

- Legal, licensing, and standards considerations are pivotal for streaming, stems, and user-generated remixes.

Glossary

- Additivity: A property of linear maps where the sum of inputs maps to the sum of outputs. "Additivity: the map preserves addition."

- Amplitude scaling: An invertible transformation that rescales STFT amplitudes (often boosting high frequencies) before decoding. "We use a complex-valued \ac{STFT} followed by the invertible amplitude scaling $\amplitudetransform: \C \to \C = \beta|c|^\alpha e^{i\angle(c)}$ (with and )..."

- Autoencoder (AE): A neural network with an encoder and decoder that learns compressed representations and reconstructs inputs. "Modern \acp{AE} can achieve excellent reconstruction quality at high compression rates at the expense of complex, entangled latent spaces."

- Consistency Autoencoder (CAE): A diffusion autoencoder whose decoder is a consistency model enabling single-step decoding. "A specific instance of \acp{DiffAE} is the \ac{CAE}\cite{pasiniMusic2LatentConsistencyAutoencoders2024,pasiniMusic2Latent2AudioCompression2025}, where the decoder is a \ac{CM}, enabling decoding in one step."

- Consistency Model (CM): A generative model that maps noisy inputs directly to clean outputs via probability flow, enabling single-step generation. "\acp{CM} \cite{songConsistencyModels2023} accelerate this process by mapping any point along the trajectory defined by the probability flow ordinary differential equation \cite{songScorebasedGenerativeModeling2021} directly to the origin (the clean data point), enabling single-step generation."

- Consistency Training (CT): A student–teacher training procedure for consistency models using denoising at different noise levels. "When trained from scratch, the process is called \acf{CT}, in which a 'student' denoiser network (\denoiser) is trained to match the output of a 'teacher' ($f_{\theta^{-}$), which itself denoises a less corrupted version of the same data point."

- Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM): Generative models that learn to reverse a gradual noising process to sample from data distributions. "Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models \cite{hoDenoisingDiffusionProbabilistic2020a} and score-based models \cite{songScorebasedGenerativeModeling2021} have achieved great success in generative modeling, where the goal is to estimate the underlying data distribution from samples."

- Denoising U-Net: A U-Net architecture adapted to predict denoised outputs, often conditioned on a latent and noise level. "The decoder is a denoising U-Net and the latent is introduced to it at every resolution level after learned upsampling."

- Diffusion Autoencoder (DiffAE): An autoencoder whose decoder is a diffusion model, enabling high-fidelity reconstructions. "\acp{DiffAE} \cite{preechakulDiffusionAutoencodersMeaningful2022,birodkarSampleWhatYou2024, chenDiffusionAutoencodersAre2025,zhaoEpsilonvaeDenoisingVisual2024, schneiderMousaiEfficientTexttomusic2024} enable high-fidelity reconstruction by replacing the deterministic decoder with a conditional diffusion model."

- Equivariance: A property where applying a transformation to the input corresponds to a predictable transformation of the output. "thereby inducing homogeneity (equivariance to scalar gain) and additivity (the decoder preserves addition)..."

- Exponential Moving Average (EMA): A smoothed average of model parameters used for stable inference. "We track an \ac{EMA} of the model parameters to be used for inference, updated every $10$ steps."

- Homogeneity: A property of linear maps where scaling the input scales the output by the same factor. "Homogeneity: scaling the input by a value scales the output by the same value;"

- iCT (improved Consistency Training): A CT variant where the teacher is updated from the student parameters but detached from gradients. "In \ac{iCT} \cite{songImprovedTechniquesTraining2023}, the teacher is updated with the same parameters as the student but detached from the computational graph ()."

- Kernel Audio Distance (KAD): A metric comparing distributions of audio embeddings for evaluation of generative models. "The \ac{KAD} \cite{chungKADNoMore2025} between the embedding distributions of the original and reconstructed tracks..."

- Latent arithmetic: Performing algebra (e.g., addition, subtraction, scaling) in the latent space to achieve audio operations like mixing or separation. "We test the practical utility of our learned space on music source composition and separation via simple latent arithmetic."

- Log-mel spectrogram: A time–frequency representation using mel-scaled frequency bands with logarithmic amplitude. "A \ac{MSS} between the original and reconstructed log-mel spectrograms using multiple resolutions..."

- Mixit: An unsupervised approach for source separation using mixtures, here used for data augmentation. "Inspired by Mixit \cite{wisdomUnsupervisedSoundSeparation2020}, we augment our data by creating artificial mixes from pairs of elements randomly selected from the training set."

- Multi-Scale Spectral distance (MSS): A metric measuring spectral differences across multiple time–frequency resolutions. "A \ac{MSS} between the original and reconstructed log-mel spectrograms using multiple resolutions..."

- Music2Latent: A CAE architecture for high-quality single-step audio reconstruction at high compression. "The approach is demonstrated with the Music2Latent architecture \cite{pasiniMusic2LatentConsistencyAutoencoders2024}, a \ac{CAE} that achieves high-quality, single-step reconstruction and a compression rate for $44.1$ kHz audio."

- Oracle source separation: Separation that leverages ground-truth or ideal information (here via known latents) to benchmark best-case performance. "Oracle Music Source Separation via latent arithmetic."

- Overlap-add: A reconstruction technique that combines processed overlapping audio chunks to form the full signal. "We reconstruct the full track using overlap-add and compute three metrics:"

- Positional embeddings: Encodings added to network layers to represent noise level or positional information. "Noise level information is added to every layer via positional embeddings."

- Probability flow ordinary differential equation (PF-ODE): An ODE describing deterministic sampling trajectories used by consistency models. "trajectory defined by the probability flow ordinary differential equation \cite{songScorebasedGenerativeModeling2021}"

- Pseudo-Huber loss: A smooth loss function approximating the Huber loss, used here for denoising objectives. " is the Pseudo-Huber loss \cite{charbonnierDeterministicEdgepreservingRegularization1997}: , with ."

- RAdam: The Rectified Adam optimizer variant that stabilizes adaptive learning rates. "The models are optimized with RAdam with learning rate (linear warmup for $10$K steps, cosine decay for the rest)."

- Scale-invariant Signal to Distortion Ratio (SI-SDR): A source separation metric that is invariant to scaling of the signal. "The quality of the separated source is evaluated against the autoencoded ground-truth source, , using \ac{SI-SDR} \cite{lerouxSDRHalfbakedWell2019} and \ac{MSS}."

- Score-based models: Generative models that learn the gradient of the log-density (score) and use it to sample data. "Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models \cite{hoDenoisingDiffusionProbabilistic2020a} and score-based models \cite{songScorebasedGenerativeModeling2021} have achieved great success in generative modeling..."

- Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT): A time–frequency analysis method that computes Fourier transforms on short overlapping windows. "We use a complex-valued \ac{STFT} followed by the invertible amplitude scaling..."

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): A metric quantifying reconstruction fidelity by comparing signal power to noise power. "The \ac{SNR} on the waveform."

- U-Net: A convolutional encoder–decoder architecture with skip connections used for denoising and reconstruction tasks. " is upsampled with a dedicated network mirroring the U-Net's upsampling block and added to each layer of the U-Net."

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): A probabilistic autoencoder trained via variational inference, often used for generative modeling. "In audio, popular \acp{AE} include Neural Audio Codecs \cite{defossezHighFidelityNeural2023}, which compress audio into a set of discrete tokens, and \acp{VAE} \cite{kingmaAutoencodingVariationalBayes2014}, which have seen significant success in generative modeling."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.