Verification Limits Code LLM Training (2509.20837v1)

Abstract: LLMs for code generation increasingly rely on synthetic data, where both problem solutions and verification tests are generated by models. While this enables scalable data creation, it introduces a previously unexplored bottleneck: the verification ceiling, in which the quality and diversity of training data are fundamentally constrained by the capabilities of synthetic verifiers. In this work, we systematically study how verification design and strategies influence model performance. We investigate (i) what we verify by analyzing the impact of test complexity and quantity: richer test suites improve code generation capabilities (on average +3 pass@1), while quantity alone yields diminishing returns, (ii) how we verify by exploring relaxed pass thresholds: rigid 100% pass criteria can be overly restrictive. By allowing for relaxed thresholds or incorporating LLM-based soft verification, we can recover valuable training data, leading to a 2-4 point improvement in pass@1 performance. However, this benefit is contingent upon the strength and diversity of the test cases used, and (iii) why verification remains necessary through controlled comparisons of formally correct versus incorrect solutions and human evaluation: retaining diverse correct solutions per problem yields consistent generalization gains. Our results show that Verification as currently practiced is too rigid, filtering out valuable diversity. But it cannot be discarded, only recalibrated. By combining calibrated verification with diverse, challenging problem-solution pairs, we outline a path to break the verification ceiling and unlock stronger code generation models.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview: What this paper is about

This paper looks at how we train AI models to write code using fake (synthetic) training data, and why the way we “check” that data can hold models back. When AI-generated code is kept only if it passes AI-made tests, the whole process depends on how good those tests are. If the tests are too simple or too strict, many good and diverse solutions get thrown away. The authors call this problem the “verification ceiling” — like a low ceiling that stops the model from getting better. The paper studies how to design better checks so we keep useful data without letting in too much bad code.

Key Questions (in simple terms)

The paper answers three main questions:

- What should we check? Does having smarter tests or just more tests help?

- How should we check? Do we really need a perfect 100% pass rate, or can we accept “good enough” code?

- Why do we need checking at all? If strict checking sometimes hurts, does correctness still matter?

How they studied it (methods, explained simply)

- They trained a medium-sized AI model (about 7 billion parameters) to write code and tested it on standard coding benchmarks in Python, C++, Java, and JavaScript. Performance is measured with “pass@1,” which means: does the model’s first answer pass the tests?

- They built training sets using:

- Synthetic problems, tests, and solutions made by strong teacher models.

- A fixed amount of high-quality public code problems.

- A small mix of non-code tasks so the model stays generally useful.

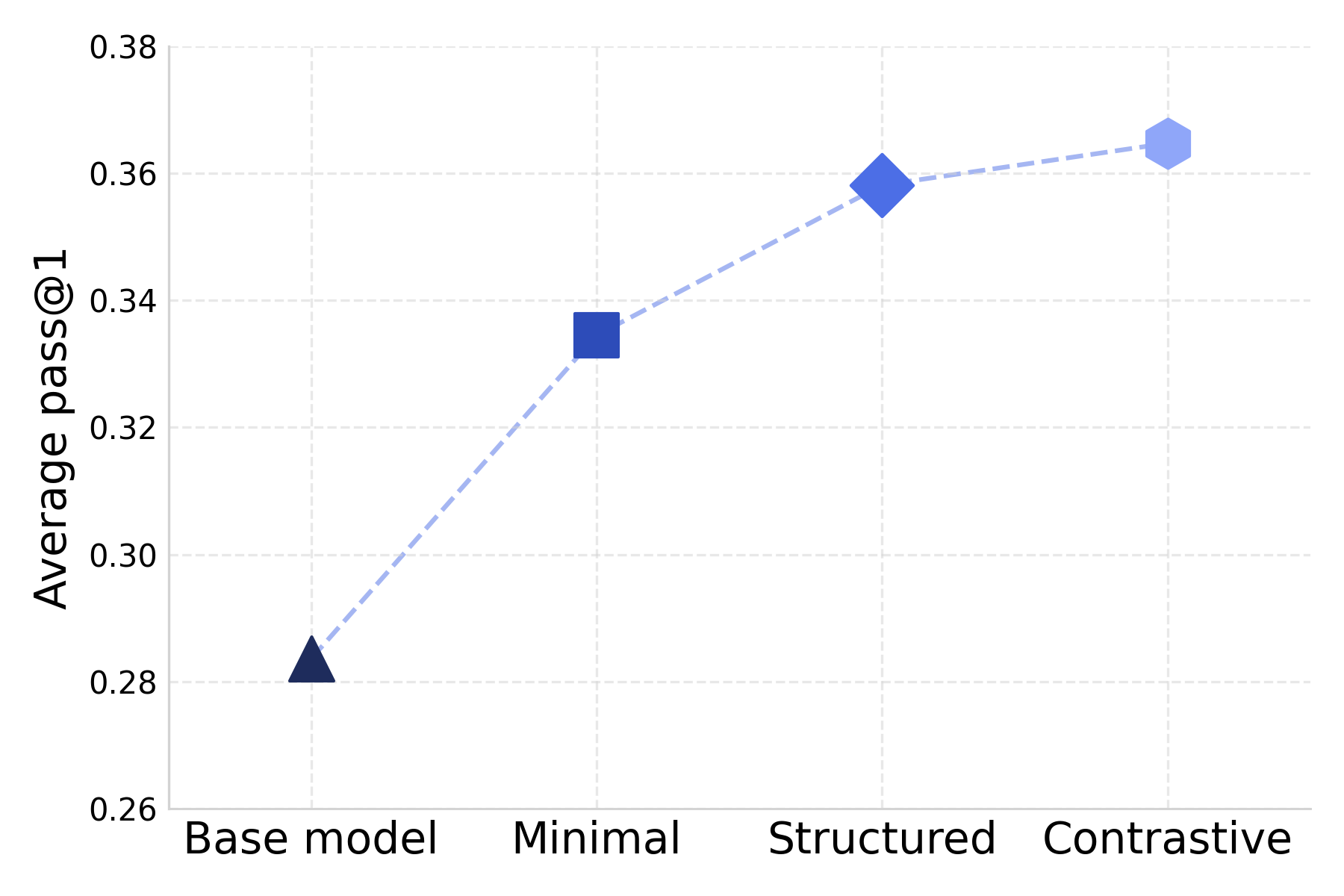

- They compared different ways of creating and using unit tests (small programs that check if a function works): 1) Minimal tests: basic checks. 2) Structured tests: smarter checks that target edge cases and under-tested logic. 3) Contrastive tests: tricky tests designed to make at least one candidate solution fail, so they catch subtle mistakes.

- They also explored:

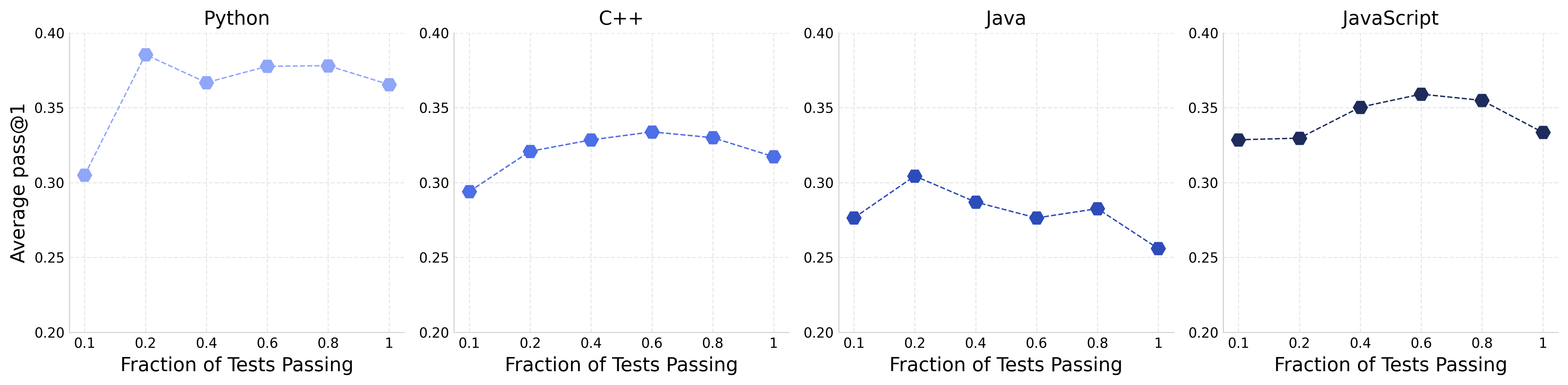

- Quantity: using 1, 2, 3, or 4 tests per problem.

- Thresholds: accepting solutions that pass, for example, 60–80% of tests instead of 100%.

- LLM-as-judge: having a different AI read the code and decide if it seems correct and good, even without running tests.

- Human review: programmers evaluated the quality of AI-made tests.

- Correct vs. incorrect training: training on the same problems but with either correct or incorrect solutions to see if correctness really matters.

Think of the tests like a referee in a game. A smarter referee who understands the rules deeply is better than adding more referees who don’t see much. Also, a referee who can score performance on a scale (not just yes/no) can keep more creative plays that are mostly right.

Main Findings (what they discovered and why it matters)

- Smarter tests beat simple tests:

- Moving from minimal to structured tests boosted performance by about +3 pass@1 points.

- Contrastive tests added about +1 more.

- Bottom line: better-designed tests let the model learn from richer, more challenging code.

- More tests isn’t always better:

- Two tests were better than one (+3 points), but adding more than two started to hurt performance.

- Why? Extra tests (if not smarter) often remove harder, more interesting problems. That leads to a simpler training set and a model that struggles with tough tasks.

- Training on harder problems helps:

- When they intentionally included more difficult problems in training, the model improved by about +6 pass@1 points on average—even when not all solutions passed every test.

- This shows we should keep challenging examples instead of filtering them out too aggressively.

- “Good enough” can be better than “perfect”:

- Requiring 100% test passes (perfect scores) was often worse than accepting solutions that passed around 60–80% of tests.

- However, this works best when the tests themselves are strong. With weak tests, relaxing the threshold just lets in more bad code.

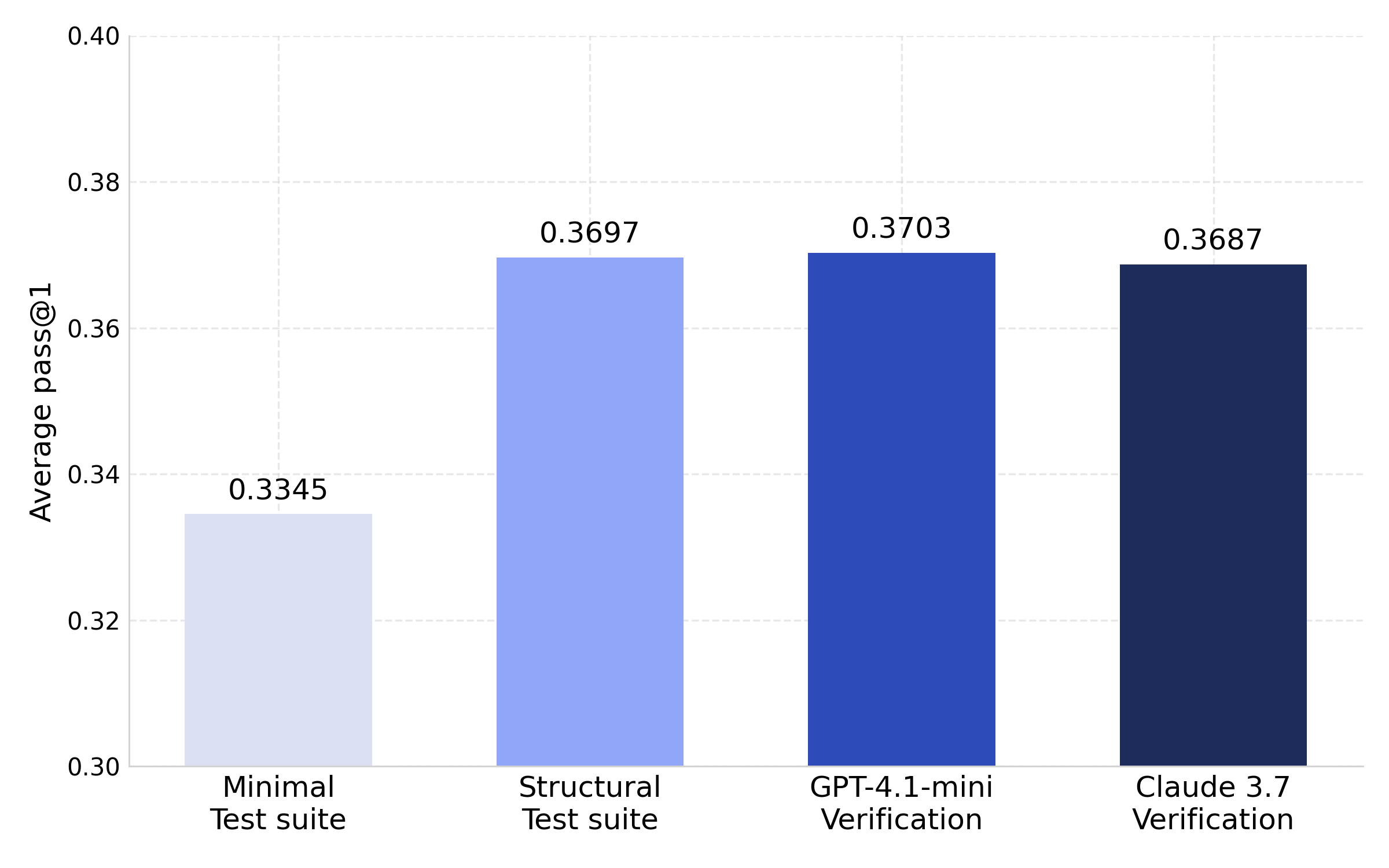

- Using an AI as a judge can work:

- Letting another strong AI score code quality (without running tests) produced training data that performed as well as strong test-based filtering and better than minimal tests.

- Different judges keep different good solutions, so they add variety that rigid tests miss.

- Human experts found many AI-made tests were incomplete:

- Only about 21% of synthetic test suites were both correct and complete.

- Over half were correct but incomplete, meaning they missed important edge cases. This explains why some good solutions get wrongly rejected.

- Agreement between AI-made tests and expert-made tests was low, showing synthetic tests can be unreliable alone.

- Correctness still matters:

- Training on sets of truly correct solutions beat training on incorrect ones by about +3 pass@1 points, when comparing the same problems.

- So we can relax and diversify verification, but we cannot ignore correctness.

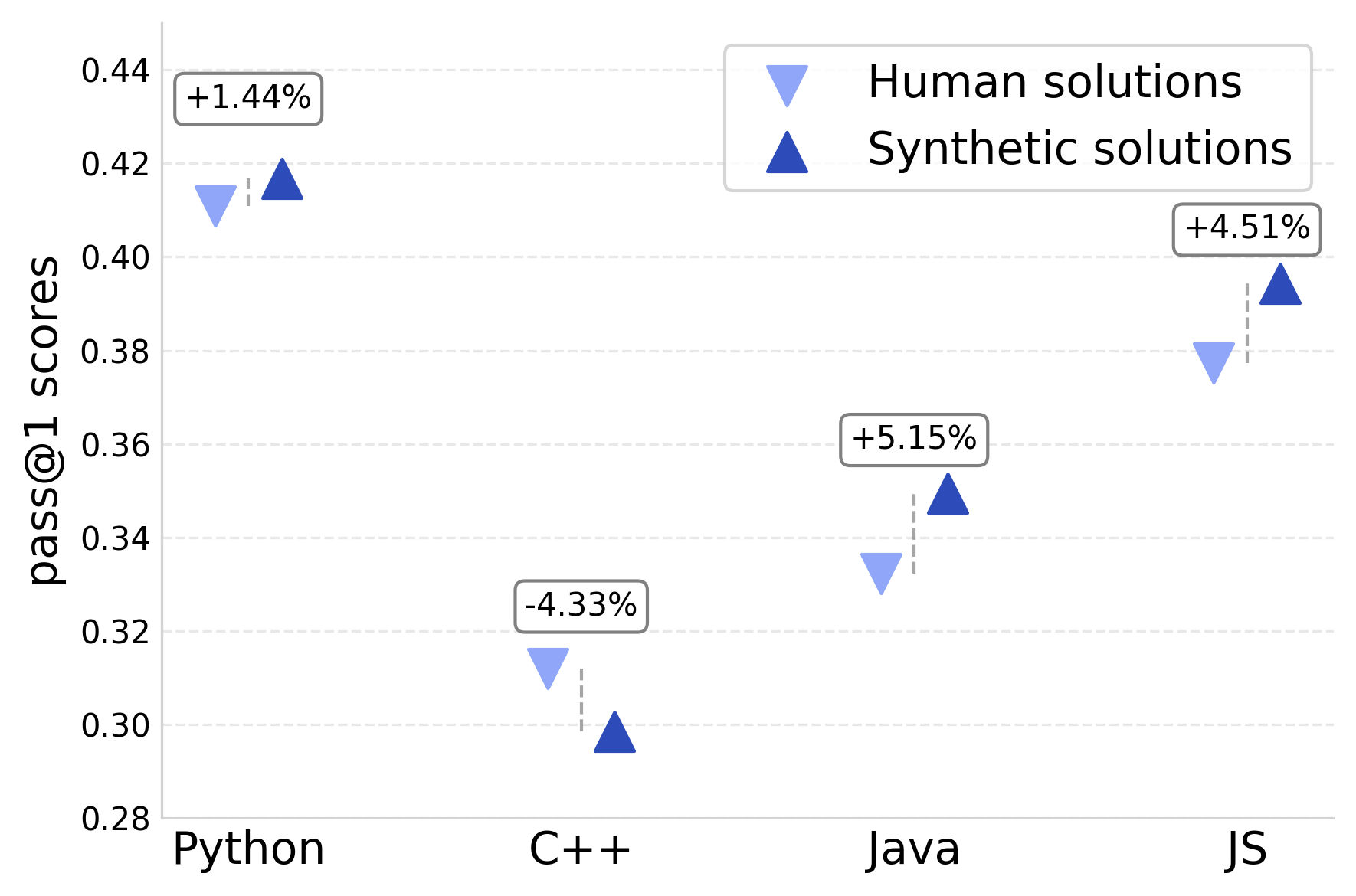

- Synthetic code is a strong alternative to human-written code:

- Models trained on synthetic solutions performed close to models trained on human solutions (within about 1 point on some benchmarks), which is promising for scaling.

What this means (implications and impact)

- Don’t just add more tests—make them smarter. Structured and contrastive tests raise the “ceiling” by catching deeper mistakes without blocking creative, valid solutions.

- Be flexible with pass rates. Demanding perfection often throws away useful training examples. Accepting mostly-correct solutions (especially under strong test suites) can build better models.

- Mix verification methods. Combining improved unit tests with AI judges and human-in-the-loop reviews can keep data high-quality and diverse.

- Keep hard problems in the mix. Overly strict filters remove the tough examples that actually teach the model the most.

- Verification is essential—but should be calibrated, not rigid. The goal is to balance correctness with diversity so models learn to solve real, challenging coding tasks.

In short, the paper shows a practical path to train stronger code-writing AIs: use richer tests, allow graded correctness, bring in multiple judging signals, and protect the diversity and difficulty of training data. This helps break through the “verification ceiling” and build better, more general code generation models.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single, focused list of the most concrete gaps that remain unresolved and that future work could address.

- Generalization across base models: Results are reported for a single 7B base model; replicate across different sizes/architectures (e.g., 1–70B, decoder-only vs. MoE) to test whether verification-ceiling effects and recommended settings (e.g., τ ≈ 0.6–0.8, structured/contrastive tests) hold broadly.

- Teacher model dependence: Synthetic solutions and tests are generated primarily with DeepSeek-v3; quantify how verifier quality and outcomes vary with other generators (e.g., GPT-4.x, Claude, Llama, Qwen), and whether ensembles reduce ceiling effects.

- Objective test-suite strength measurement: Replace LLM “judge-of-tests” with programmatic metrics (e.g., statement/branch/path coverage, mutation score, differential testing) to quantify test suite strength and tie τ selection to measurable coverage.

- Adaptive τ per problem: Develop methods to estimate per-problem verification confidence (e.g., via coverage/mutation metrics or test diversity) and set τ adaptively rather than globally to retain valuable partially correct solutions when tests are strong.

- Multi-turn test refinement: Systematically study iterative test generation with execution feedback (and counterexamples) to quantify gains in coverage, disagreement with LLM judges, and downstream performance over one-shot test creation.

- Hybrid verification fusion: Design and evaluate principled ways to combine signals from unit tests, LLM-as-judge scores, static analysis, property-based testing, fuzzing, and symbolic execution; compare simple thresholds vs. learned fusion models.

- LLM-as-judge calibration and reliability: Measure judge agreement (inter-rater reliability across models), bias to stylistic idioms, susceptibility to superficial features, and correlation with execution-based ground truth; develop calibrated scoring scales and decision rules.

- Language-specific verification behavior: Explain why verifier diversity helps C++/Java but not Python/JS (e.g., due to runtime semantics, type systems, tooling); build language-tailored verification strategies and test harnesses.

- Scaling laws for verification: Map performance as a function of dataset size, test complexity, test quantity, and τ; identify non-monotonic regimes and optimal operating points under fixed compute budgets.

- Cost–benefit analysis: Quantify generation and compute costs for structured/contrastive tests, multi-teacher verifiers, and LLM judges; optimize verification choices under latency and budget constraints.

- Solution diversity metrics: Define actionable diversity measures (algorithmic strategy classes, API usage, idioms, complexity) and test the causal effect of per-problem solution multiplicity on generalization; find the optimal number of diverse correct solutions to retain.

- Failure mode taxonomy: Categorize common mis-verification and solution failures (e.g., edge-case gaps, non-determinism, floating point, IO/statefulness, environment assumptions) and link them to specific test-generation remedies.

- Hardness estimation validity: Validate LLM-derived difficulty labels against objective metrics (e.g., algorithmic complexity, required concepts) and across benchmarks; ensure “hard problem enrichment” does not rely on noisy hardness proxies.

- Non-functional quality dimensions: Extend evaluation beyond pass@1 to readability, maintainability, security, efficiency, and best-practices adherence; develop automated metrics and test whether verification choices affect these properties.

- Security-aware verification: Detect and penalize insecure patterns (e.g., unsafe IO, injection, concurrency hazards) during filtering; integrate static/dynamic security analyzers into the verification pipeline.

- Inference-time strategy interplay: Study how training with partially correct solutions or relaxed τ interacts with pass@k, self-consistency, and reranking at inference-time; identify best joint training–inference schemes.

- Reinforcement learning with verification signals: Move beyond SFT to reward shaping using verification outcomes (execution-, coverage-, judge-based rewards, or multi-signal rewards); compare RLHF/RLAIF variants and sample efficiency vs. SFT.

- Contamination and leakage checks: Rigorously audit training–eval overlap (problem statements, unit tests, solutions) across datasets; publish leakage detection methodology specific to code tasks and synthetic pipelines.

- Environment and flakiness: Quantify test nondeterminism and environment sensitivity (library versions, platform differences); introduce stability checks and sandbox standardization to avoid false negatives/positives.

- Multi-language synthetic test generation: Systematically compare prompt templates and test generation strategies across languages; create language-specific guidance to avoid implicit bias toward particular coding styles or toolchains.

- Theoretical characterization: Formalize bounds relating attainable data quality/diversity to test coverage and τ; derive conditions under which soft verification strictly dominates hard thresholds, and when it admits harmful noise.

- Human-in-the-loop scalability: Design active-learning loops that target samples with low coverage or high verifier disagreement; quantify annotation cost, coverage gains, and downstream impact across languages and problem types.

- Data mixture side effects: Evaluate how the fixed 5% non-code instruction data affects code generation and generalist capabilities; test for catastrophic forgetting and optimal non-code proportions under different verification regimes.

- Reproducible verification benchmarks: Create and release benchmarks and tooling that measure “verification quality” (coverage, mutation, disagreement with humans/LLMs), enabling standardized comparisons of verification strategies and pipelines.

Glossary

- Adversarial examples: Test cases crafted to deliberately expose differences between solutions by causing at least one to fail, often used to probe robustness. "This encourages the generation of adversarial and high-coverage examples that explicitly differentiate between correct and incorrect behavior."

- Calibrated verification: A verification approach that avoids being overly strict or lenient to balance correctness with diversity. "We argue for calibrated verification where correctness filtering is neither too lenient nor too strict and for diverse, challenging problem–solution pairs that promote generalization without overfitting to verifier-specific patterns."

- Closed loop: A feedback cycle where model-generated solutions and verifiers limit each other, potentially excluding valid yet unrecognized solutions. "we risk creating a closed loop in which only solutions recognizable to the verifier survive, excluding potentially correct, diverse, or complex implementations that exceed its competence."

- Code coverage: The extent to which tests exercise different paths or logic in the code under test. "This approach encourages more targeted verification and improved code coverage."

- Cohen's Kappa (κ): A statistical measure of inter-rater agreement that accounts for chance. "We use Cohen's Kappa () to quantify the agreement between different types of unit tests."

- Contrastive pairs: Matched sets of passing and failing solutions for the same problem, used to isolate the effect of correctness. "coverage is bounded by the ability of the teacher model to generate such contrastive pairs, which is non-trivial for harder problems."

- Contrastive Prompting: A test generation method that creates tests designed to fail at least one candidate solution, increasing discriminative power. "Contrastive Prompting: Given the problem description , multiple candidate solutions , and an initial test suite , we ask the model to generate new tests such that at least one of the solutions fails each test."

- Contrastive unit tests: Unit tests generated to distinguish between solutions by ensuring some fail, improving selectivity. "Contrastive unit tests provide further improvements over Structured (+1 pass@1) and deliver the highest overall performance"

- Execution feedback: Runtime signals (e.g., errors, failed tests) used to guide subsequent solution attempts. "hard problems are allowed to have multiple attempts given the execution feedback from the previous failed generation."

- Formally correct: A solution that satisfies the specified formal verification criteria (e.g., passes tests). "models trained on 'formally correct' solutions outperform those trained on 'formally incorrect' ones by +3 pass@1"

- Formally incorrect: A solution that fails the formal verification criteria even if it may be partially correct or useful. "models trained on 'formally correct' solutions outperform those trained on 'formally incorrect' ones by +3 pass@1"

- High-resolution verification signal: A rich, fine-grained signal from strong tests that can support nuanced selection (e.g., partial passes). "Richer test suites provide a higher-resolution verification signal, enabling soft filtering that retains diverse, non-canonical solutions while maintaining some level of correctness."

- Human-in-the-loop judgments: Incorporating human review or decision-making within an automated pipeline to improve reliability. "hybrid verification strategies that combine automated filters with more capable LLM or human-in-the-loop judgments."

- Leakage-free: Data that avoids contamination from training sources to ensure fair evaluation. "A newer (leakage-free) set of competitive programming questions."

- LLM-as-a-judge: Using a LLM to evaluate candidate solutions directly instead of strict programmatic tests. "such as relaxing strict pass thresholds or using LLM-as-a-judge signals"

- LLM-based filters: Selection mechanisms where LLM judgments determine which samples enter training. "both LLM-based filters produce training data that leads to strong downstream performance, comparable to or exceeding that of unit test–based filtering in some settings"

- LLM-based soft verification: Using LLM judgments to provide a graded correctness/plausibility signal rather than binary test outcomes. "By allowing for relaxed thresholds or incorporating LLM-based soft verification, we can recover valuable training data"

- LLM-based verification: Verification strategies that rely on LLM assessments instead of or in addition to executable tests. "Comparison of unit test–based and LLM-based verification strategies."

- LLM-based verifier: A model that scores candidate solutions for plausibility and likely correctness. "we replace the traditional unit-test-based verification function with an LLM-based verifier that scores the solution"

- Minimal Prompting: A basic test-generation approach that prompts for simple tests from only the problem description. "Minimal Prompting: Given only the problem description , we prompt the model to generate a set of unit tests and also include tests for non-trivial inputs."

- Model collapse: Degradation in model quality due to feedback loops from training on low-diversity or self-generated data. "model collapse"

- Next-token prediction: The standard language modeling objective of predicting the next token given previous context. "self-supervised objectives such as next-token prediction"

- Partial-pass filtering: Admitting solutions that pass a high fraction of tests rather than requiring perfection. "We first investigate partial-pass filtering, where we accept solutions that pass a high (but not perfect) fraction of the test suite."

- Pass rate thresholds (τ): The required fraction of tests a solution must pass to be accepted. "pass rate thresholds ()"

- pass@1: The proportion of problems solved correctly on the first try (single sample), a standard code-generation metric. "Average pass@1 across all evaluation benchmarks for models trained with different test suite complexities."

- Relaxing thresholds: Lowering the strictness of pass criteria to admit partially correct solutions. "Relaxing thresholds under Minimal test suites degrades performance as weak tests admit noisy solutions."

- Self-supervised objectives: Learning objectives that use inherent structure in unlabeled data (e.g., predicting masked or next tokens). "pre-trained on trillions of tokens of unlabeled text using self-supervised objectives such as next-token prediction"

- Soft filtering: Selection that allows near-miss or partially correct samples when evidence suggests usefulness. "soft filtering can enhance learning, but only when the underlying verification is strong enough to provide a high-resolution correctness signal."

- Structured Prompting: A test-generation strategy that targets edge cases and under-tested logic to increase coverage. "Structured Prompting: Given a problem description , a candidate solution , and a set of minimal unit tests , we prompt the model to generate a new set of tests that are more complete specifically target edge cases and under-tested logic."

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): Further training of a pretrained model on labeled input-output pairs to specialize it for tasks. "Base refers to the pretrained model without SFT"

- Teacher models: Stronger models used to generate candidate solutions, tests, or guidance for training another model. "we generate a set of candidate solutions using one or more teacher models."

- Test suite complexity: The sophistication of tests (e.g., edge cases, adversarial checks) used for verification. "Average pass@1 across all evaluation benchmarks for models trained with different test suite complexities."

- Verifiable reward signals: Automatically checkable indicators of correctness used to guide data selection or learning. "domains with verifiable reward signals, such as code, where correctness can be automatically tested."

- Verifier diversity: Using multiple, distinct test generators/verifiers to broaden coverage and reduce bias. "Effect of verifier diversity on model performance."

- Verification ceiling problem: A bottleneck where data quality and diversity are limited by the verifier’s capability. "We refer to this bottleneck as the verification ceiling problem."

- Verification function: A mapping that scores how many tests a solution passes, often used with a threshold to filter data. "The verification function measures the fraction of tests passed"

- Verification signal: The information provided by a verification method that indicates solution quality or correctness. "Richer test suites provide a higher-resolution verification signal, enabling soft filtering that retains diverse, non-canonical solutions while maintaining some level of correctness."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now by adjusting verification design choices, training data curation, and tooling around synthetic data pipelines for code LLMs:

- Software: Calibrated verification in synthetic code data pipelines

- Use case: Replace rigid 100% pass thresholds with calibrated thresholds (e.g., τ≈0.6–0.8) when using richer test suites to recover useful training signals (+2–4 pass@1 improvements reported).

- Workflow: Implement a “Threshold Tuner” that sets τ per task family or language, with guardrails to avoid relaxation when tests are minimal.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires execution sandboxing, measurement harnesses for pass@1, and stronger unit tests (Structured/Contrastive) to avoid noise admission.

- Software/DevOps: Test suite upgrading from Minimal to Structured/Contrastive

- Use case: Improve training and CI filtering by prompting for edge cases, under-tested logic, and adversarial tests that differentiate near-correct solutions (+3 pass@1 for Structured; +1 additional for Contrastive).

- Tool/product: “TestSuite Composer” that orchestrates multi-turn test generation and contrastive sampling across candidate solutions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to strong teacher models and prompt templates; coverage and brittleness monitoring.

- Software: Difficulty-aware data sampling for SFT

- Use case: Enrich training datasets with harder problems (e.g., 40% hard, 40% medium, 20% easy) even with relaxed verification; observed average +6 pass@1 gains.

- Workflow: Add a “Difficulty Sampler” that tags and up-samples harder tasks using LLM difficulty ratings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable difficulty annotations; guardrails to prevent excessive inclusion of unsound code; language-specific calibration.

- Software: Verifier diversity (multi-generator unit tests)

- Use case: Ensemble unit test generation from multiple teacher models to broaden coverage—especially beneficial in C++ and Java (+3 and +1 points).

- Tool/product: “Verifier Orchestrator” that runs multiple test generators and merges/weights signals.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cost and latency considerations; language-dependent benefits; de-duplication and conflict resolution.

- Software: LLM-as-a-judge filtering for code solutions

- Use case: Add GPT-4.1-mini or Claude-3.7-sonnet as plausibility/correctness judges to complement unit tests; comparable performance to Structured tests and selects partially overlapping, valuable data subsets.

- Workflow: A “LLM Judge Service” microservice that scores candidate solutions for usefulness, idiomaticity, and likely correctness.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Model access and cost; clear instructions/prompts; criteria alignment with downstream goals; audit trail for decisions.

- Software/Developer Tools: CI/CD plugins for calibrated verification

- Use case: Integrate calibrated thresholds and LLM judgments into CI to evaluate AI-generated code suggestions with soft correctness signals rather than binary gates.

- Tool/product: “Calibrated CI Gate” plugin that supports τ tuning, Structured/Contrastive tests, and a fallback to strict checks for critical components.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Secure execution environment; policy exceptions for safety-critical modules; developer buy-in.

- Education: Teaching robust unit test design

- Use case: Curriculum modules that explicitly train students to produce Structured/Contrastive tests, highlighting coverage gaps found in synthetic unit tests.

- Tool/product: Classroom assignments and autograders that require adversarial tests distinguishing near-correct solutions.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to coding sandboxes; test-generation prompts adapted for education.

- Research (Academia): Replicable studies of verification ceilings

- Use case: Adopt the paper’s experimental controls (test complexity, quantity, difficulty sampling, τ relaxation, LLM-based verification) to study generalization in code LLMs.

- Tool/product: Open-source “Calibration Dashboard” to A/B test verification strategies and monitor distribution shifts (e.g., loss of hard problems when tests become too strict).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Benchmark access (HumanEval, LBPP, etc.); compute for multi-seed experiments; leakage-free datasets.

- Policy/Enterprise Governance: Internal guidelines for synthetic training data

- Use case: Define standards that document verification choices (test design, τ, LLM judging) and their observed trade-offs, with escalation to human review in safety-critical contexts.

- Workflow: “Verification Design Record” requiring teams to publish thresholds, test generation strategies, and language-specific caveats.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational processes; auditability; secure storage of training decisions.

- Daily Life (Open-source maintainers and individual developers): Practical guardrails for AI-generated code

- Use case: Combine stricter verification for critical modules with calibrated thresholds and LLM-based judgments for exploratory or non-critical code; avoid over-reliance on weak tests with relaxed thresholds.

- Workflow: Lightweight scripts to run Structured tests and an LLM judge before merging PRs from AI assistants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to testing harnesses; budget for API calls to LLM judges; clear labeling of verification status in PRs.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, or development to mature into robust, widely deployable solutions:

- Software/ML Systems: Reinforcement learning from verification signals

- Use case: Integrate calibrated verification signals (unit-test pass fractions, LLM judgments, difficulty weights) directly into reward functions for RL training.

- Product/workflow: “Verification-Aware RL” framework that uses blended correctness/diversity rewards to push beyond the current ceiling.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable RL training setups; safety checks to avoid reward hacking; scalable evaluators.

- Software/Static Analysis: Hybrid formal verification + LLM judging

- Use case: Combine static analysis, symbolic execution, and coverage-guided fuzzing with LLM judges to create high-resolution, robust correctness signals.

- Product/workflow: “Hybrid Verif Pipeline” that orchestrates formal tools, dynamic tests, and LLM review in a unified scoring schema.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Integration complexity; per-language tooling quality; compute overhead.

- Cross-sector Safety (Healthcare, Finance, Energy, Robotics): Domain-calibrated verification frameworks

- Use case: Sector-specific calibration of thresholds, mandatory human-in-the-loop for high-risk code, and stricter verification gates for safety-critical paths (e.g., medical device firmware, trading systems, PLCs).

- Product/workflow: “Safety Calibration Profiles” that encode domain rules: strict τ=1 for critical subsystems, calibrated τ for non-critical modules, and mandatory human review for certain failure modes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory buy-in; domain-specific test suites; secure execution and provenance tracking.

- Cloud Platforms/MLOps: Managed verification-as-a-service

- Use case: Offer hosted services for Structured/Contrastive test generation, multi-verifier orchestration, and LLM judging with per-language optimizers.

- Product/workflow: “Verification Service Mesh” with autoscaling executors, audit logs, and policy controls for enterprise consumers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Security (sandboxing untrusted code), cost management, SLAs.

- Metrics and Evaluation: Beyond pass@1—multi-dimensional code quality

- Use case: Standardize metrics for readability, maintainability, efficiency, security, and best-practice adherence; blend these with functional correctness in selection pipelines.

- Product/workflow: “Code Quality Scorer” API combining static/dynamic analyses and LLM assessments into a composite score.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Agreement on definitions and benchmarks; evaluator bias mitigation; language/lint diversity.

- Data Governance and Policy: External standards for synthetic training pipelines

- Use case: Industry-wide specifications requiring disclosure of verification strategies, thresholds, and test coverage; independent audits to mitigate model collapse risks and synthetic-data brittleness.

- Product/workflow: “Synthetic Data Governance Standard” and certification program for code LLM providers.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder coordination; privacy and IP concerns; enforcement mechanisms.

- Research (Academia): Verifier ensemble theory and adaptive τ selection

- Use case: Formalize ensemble weighting of multiple verifiers (tests, static analysis, LLM judges) and derive optimal τ per data slice based on uncertainty and coverage.

- Product/workflow: “Adaptive Verification Controller” that tunes selection criteria in real time using uncertainty estimates and distribution monitoring.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust uncertainty estimation; drift detection; reproducible theory-to-practice bridges.

- Education/Workforce Development: Test-centric curricula and tooling

- Use case: Large-scale adoption of Structured/Contrastive test design training, plus tools that help learners see how overzealous verification removes hard problems and harms generalization.

- Product/workflow: “Test Literacy Suite” with lesson plans, interactive sandboxes, and analytics on coverage and difficulty.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Institutional adoption; funding for educational tooling; localized language support.

- Open Benchmarks and Datasets: Leakage-free, difficulty-balanced, verifier-diverse corpora

- Use case: Curate public datasets that control for problem difficulty, test suite richness, and verifier diversity to better evaluate generalization and reduce ceiling effects.

- Product/workflow: “Verification Ceiling Benchmark” with standardized protocols for measuring the impact of verification choices.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community collaboration; sustained maintenance; guardrails against contamination.

- Developer Tools: “Verification Ceiling Radar” for pipeline health

- Use case: Monitor whether stricter filters are disproportionately removing hard problems and diversity, leading to performance plateaus.

- Product/workflow: Dashboard with alerts when distribution skews toward easy tasks due to verification tightening.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Telemetry integration; well-defined thresholds for alerts; interpretability for non-ML stakeholders.

In both immediate and long-term settings, the central dependency is the strength and diversity of verification signals. Relaxation of pass thresholds only helps when the underlying tests are rich (Structured/Contrastive) or when LLM judges are well-instructed and audited. For safety-critical sectors, strict verification and human oversight remain essential, with calibrated strategies applied selectively to non-critical components.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.