Latent Zoning Network: A Unified Principle for Generative Modeling, Representation Learning, and Classification (2509.15591v1)

Abstract: Generative modeling, representation learning, and classification are three core problems in ML, yet their state-of-the-art (SoTA) solutions remain largely disjoint. In this paper, we ask: Can a unified principle address all three? Such unification could simplify ML pipelines and foster greater synergy across tasks. We introduce Latent Zoning Network (LZN) as a step toward this goal. At its core, LZN creates a shared Gaussian latent space that encodes information across all tasks. Each data type (e.g., images, text, labels) is equipped with an encoder that maps samples to disjoint latent zones, and a decoder that maps latents back to data. ML tasks are expressed as compositions of these encoders and decoders: for example, label-conditional image generation uses a label encoder and image decoder; image embedding uses an image encoder; classification uses an image encoder and label decoder. We demonstrate the promise of LZN in three increasingly complex scenarios: (1) LZN can enhance existing models (image generation): When combined with the SoTA Rectified Flow model, LZN improves FID on CIFAR10 from 2.76 to 2.59-without modifying the training objective. (2) LZN can solve tasks independently (representation learning): LZN can implement unsupervised representation learning without auxiliary loss functions, outperforming the seminal MoCo and SimCLR methods by 9.3% and 0.2%, respectively, on downstream linear classification on ImageNet. (3) LZN can solve multiple tasks simultaneously (joint generation and classification): With image and label encoders/decoders, LZN performs both tasks jointly by design, improving FID and achieving SoTA classification accuracy on CIFAR10. The code and trained models are available at https://github.com/microsoft/latent-zoning-networks. The project website is at https://zinanlin.me/blogs/latent_zoning_networks.html.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper introduces a simple idea called “orange” that tries to solve three big machine-learning jobs with one shared system:

- Making new data (like generating images)

- Learning useful features from data without labels (representation learning)

- Sorting things into categories (classification)

Instead of building a separate model for each job, orange creates one shared “thinking space” that all jobs can use. This could make machine learning simpler and help different tasks boost each other’s performance.

The main questions the paper asks

- Can one shared idea—a single “latent space”—handle generation, representation learning, and classification?

- Can this shared space be easy to sample from (useful for generation) and also useful for understanding data (useful for learning and classification)?

- Can we train different parts (like for images and labels) so they all line up and talk to each other through this shared space?

How orange works (in everyday language)

Think of orange as a shared map where every kind of data—images, text, or labels like “cat” or “dog”—gets its own way to place pins and read pins on the map:

- An encoder is like a “pin-placer”: it takes an image (or text/label) and decides where on the map it belongs.

- A decoder is like a “map reader”: it can take a spot on the map and turn it back into an image (or text/label).

On this map:

- The overall shape is special: it follows a simple bell-curve-like pattern (a Gaussian). That makes it easy to pick random points to generate new things.

- Each specific example (like a photo of a cat) doesn’t map to just one dot—it gets its own tiny “zone” on the map. Different examples have non-overlapping zones so they don’t get mixed up.

With these pieces, different tasks become simple “routes” on the map:

- Image encoder alone → a compact, useful embedding of images (representation learning)

- Image decoder alone → make new images from random points (generation)

- Label encoder + image decoder → “draw me a dog” (class-conditional image generation)

- Image encoder + label decoder → “what is in this picture?” (classification)

To make this work, orange uses two key steps. Here they are, briefly and simply:

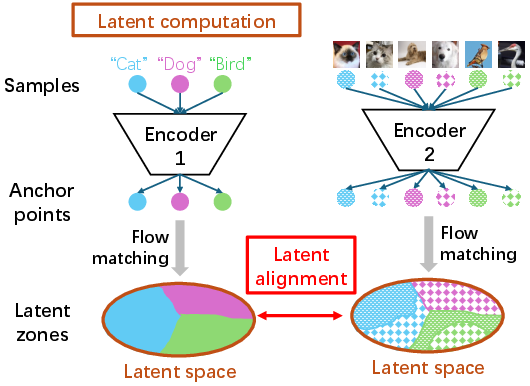

- Latent computation: The encoder first places an “anchor point” for each example. Then a smooth process called flow matching spreads these anchors into neat, non-overlapping “zones” that together fill the map in a bell-curve way. You can think of it like gently reshaping dough so it evenly fills a pan without mixing different pieces together.

- Latent alignment: Sometimes you want two things to match—like a “cat” label zone to cover all “cat image” zones. Directly forcing that match is tricky. Orange solves this by using a soft, gradual matching during the same smooth process (flow matching), which makes training stable and effective.

What the researchers did and found

The authors tested orange in three ways, moving from simpler to more complex:

1) Improving an existing image generator

They took a strong image generator (a “rectified flow” model, similar to diffusion models) and simply fed orange’s latent code into it as an extra input during training. They did not change the original training loss. Result: the image quality improved. For example, a standard metric (FID) got better (lower is better), such as from 2.76 to 2.59 on one dataset. Reconstructions also got more accurate, which suggests the latents capture meaningful details.

Why this helps: orange’s latent gives each training image a unique, informative “handle,” making the generator’s job easier and more precise.

2) Learning representations without labels

They trained just the image encoder using pairs of differently augmented versions of the same image. Instead of a contrastive loss (which is common), they used orange’s latent alignment to make sure both versions land in the same zone. Because zones for different images are designed to be separate, the model naturally avoids “collapse” (where everything looks the same).

Result: When tested by training a simple linear classifier on top of these embeddings, orange beat some classic methods, including MoCo (by 9.3%) and SimCLR (by 0.2%) on a standard benchmark with ResNet-50. It’s not the absolute best yet, but it’s impressive because orange is a unified framework, not a hand-tuned specialist.

3) Doing generation and classification together

They built image and label encoders/decoders so orange could both:

- Generate images given a label (like “bird” → bird images)

- Classify images (image → label)

Because both tasks share the same map, they helped each other. The model improved generation quality compared to a strong baseline, and also achieved top-level classification accuracy on a common dataset, outperforming training each task separately.

Why this matters

- Simpler pipelines: Instead of using three different systems (one for generating, one for learning features, and one for classifying), orange provides one shared framework.

- Tasks help each other: Better shared representations improve both generation and classification at the same time.

- Flexible and compatible: Orange can sit on top of modern generative models (like diffusion or transformers). It’s not a competitor so much as a way to unify and enhance them.

Big picture and future impact

Orange shows that a single, shared latent space—with neat “zones,” easy sampling, and careful alignment—can bring together three major machine-learning tasks. If scaled to more data types (like audio or more kinds of text), this could:

- Reduce the need for separate models and losses

- Make training more efficient

- Create systems that learn richer, more general knowledge

There are still challenges—like scaling to many data types and making training even faster—but the early results suggest orange is a promising step toward “one framework to do it all.”

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

Below is a concise list of the main uncertainties and open problems the paper leaves unresolved. Each item is phrased to be directly actionable by future researchers.

- Theoretical guarantees for “disjoint latent zones”

- The paper asserts that zones for different samples are disjoint by construction via FM/IFM, but with the practical relaxations (π1 replaced by π1−g, numerical solvers, minibatch approximations), it is unclear whether disjointness still holds in practice or how often collisions/overlaps occur.

- No formal analysis bounds the probability of latent-zone overlap as a function of g, solver step size, or minibatch size.

- Identifiability and stability of latent-zone alignment

- The soft alignment objective maximizes max_t P(a_k | s_t) over late timesteps, but there is no proof that this implies Supp(Y_i) ⊆ Supp(X_k_i) or that it leads to a unique, stable alignment.

- The effect of the non-smooth max over timesteps on optimization stability and convergence (e.g., vanishing gradients when the maximum is attained early or late) is not analyzed.

- Sensitivity to hyperparameters and solver choices

- Key hyperparameters (g for IFM start, the early-step cutoff u, number and schedule of timesteps, numerical solver choice) likely affect both zone separation and alignment quality; no systematic sensitivity or robustness study is reported.

- It is unclear whether the method is brittle to small changes in these parameters or if there are principled default settings.

- Scalability and computational overhead

- Computing the FM velocity V(s, t) requires access to all anchors; despite proposed engineering optimizations (latent parallelism, checkpointing, minibatch approximations), the paper does not quantify throughput, memory usage, or scaling laws for large datasets, high-resolution images, or long training runs.

- The impact of minibatch approximations on the fidelity of the global flow and on downstream task performance remains unmeasured.

- Generalization beyond images and labels

- Although the framework is presented as modality-agnostic, experiments are limited to images and class labels. It remains unknown how well the approach extends to text, audio, video, or structured/tabular data (including tokenizer interactions and sequence length issues).

- The practicality and benefits of adding multiple modalities simultaneously (e.g., images, text, audio) and aligning their zones are not explored.

- Handling unpaired or weakly paired cross-modal data

- The alignment formulation assumes known pairings k_i; it is unclear how to perform alignment under missing, noisy, or weak correspondences (e.g., partially paired datasets, web-scale noisy labels, or semi-supervised settings).

- Multi-task scaling and interference

- As more encoders/decoders are added, potential negative transfer, capacity contention, and conflicting alignment objectives are not analyzed. There is no curriculum or scheduling strategy for multi-task training to prevent interference.

- Expressivity and geometry of latent zones

- The paper posits zones as subsets corresponding to “the same observation,” but provides no quantitative characterization of zone volumes, shapes, margins, or how these properties vary with data complexity or augmentation policies.

- It is unknown whether zone geometry supports desirable invariances (e.g., robustness to nuisance factors) without sacrificing fine-grained information needed for generation.

- Representation learning: invariances and downstream versatility

- The method’s induced invariances are governed by the augmentation policy, but the trade-off between invariance (useful for classification) and information retention (needed for generation) is not measured.

- Only linear probing on a single architecture/dataset is reported; zero-shot classification, retrieval, transfer to diverse datasets, and few-shot tasks are not evaluated.

- Decoder choices and universality claim

- Although decoders could in principle be any generative model, the paper only instantiates with rectified flow. It remains unknown how well orange integrates with diffusion samplers (various schedules), autoregressive models, VAEs, or flow-based models, and whether alignment/zone computation interacts differently with these choices.

- Memorization and diversity risks when conditioning generators on orange latents

- The latent-per-image conditioning could lead to over-conditioning and reduced diversity or memorization risks; while precision/recall are reported, deeper analyses (nearest-neighbor checks, train-test leakage diagnostics, coverage of rare modes) are missing.

- Statistical significance and robustness of reported gains

- Improvements (e.g., FID 2.76 → 2.59) are modest; no confidence intervals, multiple seeds, or statistical tests are given to establish robustness across runs and data shuffles.

- Discretization error and flow approximation effects

- The bias introduced by starting from π1−g and discretizing the flow with a specific solver/schedule is not quantified; there is no ablation on solver type, number of steps, or adaptive error control.

- Learning dynamics and failure modes of the alignment objective

- The effect of the late-time cutoff u on gradient signal, early training dynamics (when assignments are near-uniform), and potential local minima (e.g., attraction to frequent anchors/classes) is not explored.

- No comparison to alternative alignment objectives (e.g., OT-based alignments, contrastive losses, mutual-information estimators) under controlled settings.

- Capacity and dimensionality design

- The paper does not study how latent dimensionality and encoder/decoder capacity influence zone separability, alignment quality, and task trade-offs, nor does it provide guidelines for choosing these hyperparameters.

- Robustness and OOD behavior

- The framework’s robustness to distribution shifts, corruptions, adversarial perturbations, or heavy-tailed data is unknown; the impact on zone stability and decoder reliability under OOD inputs is not tested.

- Data efficiency and low-resource regimes

- It is unclear how orange performs with limited labeled data (for alignment with labels), small unlabeled corpora, or long-tailed class distributions, and whether its benefits persist under strong data scarcity.

- Training objectives interplay in joint setups

- In joint generation+classification, the relative weighting/scheduling of objectives (RF loss vs. alignment/classification) and their interactions are not systematically studied; the risk of one task dominating or harming the other is not quantified.

- Fairness and bias

- There is no analysis of whether latent zones encode or amplify demographic or semantic biases, nor how alignment across modalities interacts with spurious correlations.

- Interpretability of zones and anchors

- While zones are central to the framework, there is no interpretability analysis (e.g., probing what semantic attributes zones/anchors capture, how they traverse along FM trajectories, or how edits in latent space translate in data space).

- Comparison to prior unified latent frameworks

- Empirical comparisons to multi-modal VAEs, InfoGAN-style approaches, or shared-latent cross-modal models are missing, leaving unclear when orange is preferable and by how much.

- Practical deployment considerations

- Inference-time efficiency when alignment or latent computation is needed (beyond the unconditional generation case) is not benchmarked; the suggested use of encoder outputs instead of full latent computation for downstream tasks lacks a thorough accuracy–latency trade-off analysis.

- Extending beyond classification to richer conditional tasks

- The viability of zones for fine-grained conditional controls (attributes, continuous controls, compositional prompts) and their composability (e.g., combining label and text “zones”) remains untested.

- Learning pairings jointly with latent zones

- The framework assumes known k_i for paired data; a promising open direction is jointly learning pairings and zones (e.g., via differentiable matching/EM-like procedures), which the paper does not attempt.

- Formalization of the “unified principle” claim

- The unification is demonstrated on a narrow set of tasks and domains; a formal scope statement (which ML tasks can/cannot be expressed via encoder–decoder compositions over shared Gaussian latents) and counterexamples are absent.

Glossary

- Anchor point: A deterministic embedding of a sample produced by an encoder, used as the seed for constructing its latent zone. "we first use the encoder to compute each sample's anchor point, then apply flow matching (FM) \cite{liu2022flow,lipman2022flow} to map these points to their corresponding latent zones."

- Auto-regressive (AR) transformers: Generative models that predict tokens sequentially, often used to unify multiple tasks through generation. "auto-regressive (AR) transformers with large-scale pre-training provide one approach to unify these tasks \cite{radford2018improving,radford2019language,brown2020language,achiam2023gpt}"

- CMMD: A metric for evaluating generative models; lower values indicate closer alignment to the target distribution. "In addition to standard metrics—FID \cite{heusel2017gans}, sFID \cite{nash2021generating}, IS \cite{salimans2016improved}, precision \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}, recall \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}, and CMMD \cite{jayasumana2024rethinking}—we also report reconstruction error"

- Collapse: In self-supervised learning, the failure mode where representations become identical for all inputs. "A central challenge is avoiding collapse, where all inputs are mapped to the same representation."

- Contrastive loss: An objective that pulls similar samples together and pushes dissimilar ones apart in representation space. "SoTA representation learning employs contrastive loss \cite{he2020momentum,chen2020simple,grill2020bootstrap};"

- Cross-entropy loss: A standard classification objective that trains models to map inputs to class labels. "The most common and SoTA classification approach trains a dedicated model with cross-entropy loss to map inputs to class labels \cite{devlin2019bert,liu2019roberta}."

- Dirac delta function: A distribution used to represent point masses (e.g., anchor points) in formal definitions. "where , the distribution of the anchor points.\footnote{ denotes the Dirac delta function.}"

- DPM-Solver: A numerical solver used to approximate integrals along flow-matching trajectories efficiently. "we approximate using standard numerical solvers such as Euler or DPM-Solver \cite{lu2022dpm,lu2022dpmp}"

- Early step cutoff: A training technique that ignores early trajectory steps to obtain informative gradients for alignment. "Technique 3: Early step cutoff."

- Flow Matching (FM): A method that constructs a one-to-one mapping between distributions via a learned velocity field. "we then apply the seminal flow matching (FM) method \cite{liu2022flow,lipman2022flow}, which establishes a one-to-one mapping between distributions, to transform these anchor points into latent zones."

- Flow Matching trajectory: The path traced by a latent under the FM velocity field from the prior to anchor points. "We can obtain by integrating along the FM trajectory: "

- Fréchet Inception Distance (FID): A metric for generative image quality; lower is better. "orange improves FID on from 2.76 to 2.59—without modifying the training objective."

- Full support: A property of distributions required for well-defined flow matching. "FM is well-defined only when both and have full support."

- Gaussian latent space: A shared latent representation constrained to follow a Gaussian distribution. "orange creates a shared Gaussian latent space that encodes information across all tasks."

- Gaussian prior: A simple normal distribution imposed on latents to enable easy sampling. "It follows a simple Gaussian prior, allowing easy sampling for generation tasks."

- Gradient checkpointing: A memory-saving technique that recomputes intermediate activations during backpropagation. "latent parallelism, custom gradient checkpointing, and minibatch approximation--that make the training of orange scalable."

- Inception Score (IS): An evaluation metric for generative models based on classifier confidence and diversity. "Inception Score (IS) is best suited for natural images like , though we report it for all datasets for completeness."

- Latent alignment: The process of aligning latent zones across data types so cross-module tasks can operate correctly. "Latent alignment (\cref{sec:lzn_latent_alignment):} Aligns latent zones across data types by matching their FM processes."

- Latent computation: The operation that encodes samples into anchor points and partitions the latent space into disjoint zones. "Latent computation (\cref{sec:lzn_latent_computation):} Computes latent zones for a data type by encoding samples into anchor points and using flow matching (FM) \cite{liu2022flow,lipman2022flow} to partition the latent space."

- Latent parallelism: An efficiency technique that parallelizes latent computations to reduce training cost. "latent parallelism, custom gradient checkpointing, and minibatch approximation--that make the training of orange scalable."

- Latent zone: A subset of the latent space corresponding to a specific observed sample in a given data type. "Each data type induces a distinct partitioning of the latent space into latent zones, where each zone corresponds to a specific sample (e.g., an individual image or label)."

- Linear head: A simple linear classifier trained on learned representations for downstream tasks. "be adapted for classification using a linear head trained with cross-entropy loss \cite{chen2020simple}."

- Many-to-one alignment: Alignment where one latent zone (e.g., a label) should cover many zones (e.g., all images of that label). "We consider two types of alignment: (1) Many-to-one (and one-to-many) alignment: for example, the latent zone of the “cat” label should cover all latent zones of all cat images."

- Masked image modeling: A self-supervised objective that reconstructs masked parts of images to learn representations. "Other unsupervised representation learning approaches \cite{sander2022residual,li2022neural} include masked image modeling \cite{li2023mage,bao2021beit,he2022masked,pai2023masked}"

- Memory banks: External storage of representations used to stabilize contrastive learning and avoid collapse. "Common solutions include pushing the representations of dissimilar samples from large batches \cite{chen2020simple} or memory banks \cite{he2020momentum} away"

- Mixture of Gaussians: A distribution comprising multiple Gaussian components, here used to describe intermediate FM states. "By construction, the distribution is a mixture of Gaussians:"

- Minibatch approximation: An efficiency technique that approximates operations using smaller subsets of data. "latent parallelism, custom gradient checkpointing, and minibatch approximation--that make the training of orange scalable."

- One-to-one alignment: Alignment where paired samples across modalities should share the same latent zone. "We consider two types of alignment: ... (2) One-to-one alignment: for example, in image-text datasets, paired image and text samples should share the same latent zone."

- Precision (generative modeling): An evaluation metric capturing sample fidelity (how realistic generated samples are). "precision \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}, recall \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}"

- Rectified Flow (RF): A generative modeling framework related to diffusion models that learns velocity fields for sampling. "rectified flow (RF) models \cite{liu2022flow}, which is closely related to diffusion models \cite{ho2020denoising,sohl2015deep,song2019generative}."

- Recall (generative modeling): An evaluation metric capturing sample diversity (coverage of the target distribution). "precision \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}, recall \cite{kynkaanniemi2019improved}"

- Reconstruction error: The ℓ2 distance between an image and its reconstruction; lower indicates better reconstruction quality. "we also report reconstruction error (the distance between an image and its reconstruction)"

- SDE sampling: A diffusion-model sampling method that introduces stochasticity via stochastic differential equations. "plus intermediate noise if using SDE sampling \cite{song2020score}."

- Soft approximation: A differentiable relaxation of a discrete assignment used to enable gradient-based alignment. "our key idea is to introduce a soft approximation of the discrete anchor assignment process."

- sFID: A variant of FID designed to be more sensitive to local image statistics; lower is better. "sFID \cite{nash2021generating}"

- Velocity field: The vector field in flow matching that drives samples from the prior toward anchor points. "The velocity field in FM \cite{liu2022flow} can then be computed as"

Practical Applications

Below is an application-focused synthesis of the paper’s contributions. It highlights concrete use cases, the sectors they touch, potential tools/workflows that could emerge, and key feasibility assumptions and dependencies.

Immediate Applications

These can be deployed now using the paper’s demonstrated image-domain results and available code.

- Upgrade training of image generators with “orange conditioning”

- Sectors: creative tooling, advertising, gaming, e-commerce, ML infrastructure

- Use case: Add orange latents as an extra condition when training rectified flow or diffusion-style image generators to improve FID/sFID and reconstruction quality without changing the loss or inference-time cost.

- Tools/workflows: PyTorch module for latent computation via flow matching (FM) and DPM-Solver; a “plugin” to existing RF/diffusion training code; training recipes that keep inference unchanged (Gaussian latent sampling).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires training-time compute for FM-based latent computation; benefits validated on images; encoder used only at training; decoders/generators remain standard models.

- Unsupervised image representation learning without contrastive loss

- Sectors: search/retrieval, recommendation, digital asset management, MLOps

- Use case: Train an orange image encoder using augmented pairs and latent alignment to obtain embeddings for downstream linear classification/retrieval, avoiding large memory banks or negative mining.

- Tools/workflows: Embedding service powered by the orange encoder; batch data-augmentation pipeline; linear-probe evaluation; integration into vector databases.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Image-only validation (ResNet-50, ImageNet); requires careful choice of FM time-step truncation and solver; training cost higher than simple encoders due to FM.

- Joint training of classifier and generator for better accuracy and sample quality

- Sectors: manufacturing defect detection (vision), content moderation, product QA

- Use case: Train a single model with image and label encoders/decoders to perform classification and class-conditional generation simultaneously, yielding better performance than training each alone.

- Tools/workflows: Unified training loop that includes label encoders (for many-to-one alignment) and image decoders (RF); class-conditioned sampling for analysis/debugging.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires paired image-label data; alignment objective hinges on late-step “soft assignment” working well; tested on standard image benchmarks.

- Class balancing and synthetic data augmentation via label-to-image generation

- Sectors: any vision classification pipeline (retail catalog, medical pre-screening, document sorting)

- Use case: Use label encoder + image decoder to synthesize class-balanced datasets or rare-class samples to improve classifier robustness.

- Tools/workflows: Data augmentation job that samples orange latents within a label’s latent zone and decodes images; automated retraining pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Quality hinges on the decoder’s generative capacity; care needed to avoid overfitting and privacy leakage when reconstructing training images.

- Lower-error image reconstruction for consistent editing and inverse problems

- Sectors: photo editing, design, digital art, AEC (architecture/engineering/construction) visualization

- Use case: Exploit substantially lower reconstruction error to enable consistent edits (e.g., latent manipulations, inpainting) and better “round-trip” fidelity.

- Tools/workflows: Latent editing UI; round-trip encode–edit–decode workflows; reconstruction-based quality checks for image pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Still image-centric; reconstruction improvements shown with RF; editing semantics depend on how latents correlate with controllable factors.

- Academic research and teaching platform for unified ML

- Sectors: academia, education

- Use case: Use the open-source implementation to teach and study a single framework that covers generation, representation learning, and classification; benchmark alternatives to contrastive learning and joint training.

- Tools/workflows: Course labs on FM-based latent computation and alignment; comparative experiments with contrastive and diffusion baselines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires familiarity with FM and numerical solvers; training compute for student labs.

- MLOps: Multi-objective training and auditing with shared latents

- Sectors: ML platform engineering

- Use case: Adopt a shared latent as the “contract” between tasks, enabling simpler multi-task training (gen + repr + cls) and unified evaluation (FID/sFID/precision/recall/reconstruction).

- Tools/workflows: Training dashboards tracking latent alignment metrics; A/B testing pipelines where only training-time conditioning changes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Additional monitoring for alignment stability; careful hyperparameterization (e.g., step cutoffs u).

- Privacy-aware synthetic data sandboxes (with safeguards)

- Sectors: regulated industries needing de-identified image data (healthcare-like preclinical research, finance KYC images)

- Use case: Generate synthetic samples from Gaussian latents for experimentation and prototyping where real data cannot be shared.

- Tools/workflows: Synthetic data generators with knobs for diversity vs. fidelity; risk assessment workflows (e.g., distance-to-training-sample checks, DP add-ons).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reconstruction strength raises re-identification risk if not mitigated; requires privacy safeguards (differential privacy/noise, membership inference checks).

Long-Term Applications

These need further research, scaling, or modality expansion beyond images to realize.

- Multimodal foundation backbone with a single shared latent space

- Sectors: software/AI platforms, content ecosystems

- Use case: Unify images, text, audio, video, and labels via separate encoders/decoders but a shared Gaussian latent, enabling seamless cross-modal tasks (e.g., image↔text, audio→video captions).

- Tools/products: “Unified encoder/decoder zoo” with orange-compatible interfaces; cross-modal authoring tools; APIs for encoder–decoder composition.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires high-quality decoders per modality; robust many-to-one and one-to-one alignment across modalities; scaling FM to massive, heterogeneous datasets.

- Robotics and autonomous systems: shared world-state latents

- Sectors: robotics, automotive, drones, logistics

- Use case: Map multi-sensor inputs (camera, LiDAR, IMU, radar) into a common latent “world state,” and decode to predictions, plans, or simulated sensor views; unify perception, prediction, and control training.

- Tools/workflows: Real-time approximate FM, sensor-specific encoders/decoders, simulation-in-the-loop training via latent rollouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Real-time constraints; safety-critical validation; action decoding may need additional control-aware objectives.

- Healthcare: multi-modal clinical modeling and data augmentation

- Sectors: healthcare, biomedical research

- Use case: Unify imaging (CT/MRI/pathology), reports/notes, and labels to support diagnosis, cross-modal retrieval, and class-conditional generative augmentation for rare conditions.

- Tools/products: Research platforms for radiology–report alignment; synthetic cohort generation under physician control.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strict regulatory validation (FDA/EMA); bias and safety audits; privacy-preserving training; domain-specific decoders.

- Document and enterprise AI with cross-format unification

- Sectors: finance, insurance, legal, operations

- Use case: Jointly learn from scanned images, OCR text, layout graphs, and labels to improve classification, retrieval, and synthetic document generation for testing.

- Tools/workflows: Pipelines with encoders for forms, tables, and text; label-conditioned synthetic documents for pipeline QA.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-quality text/layout decoders; robust pairing/alignment; prevention of leakage of sensitive data.

- Education and assistive technologies: cross-modal creation and assessment

- Sectors: edtech, accessibility

- Use case: Generate and classify educational content across text–image–audio; align captions and images for accessible materials; assess content quality using shared latents.

- Tools/products: Content studio for teachers; caption–image alignment checkers; assistive apps for multi-sensory learning.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Strong multimodal decoders; pedagogy-aligned evaluation; content safety and factuality.

- Industrial and energy: fault detection with generative diagnostics

- Sectors: manufacturing, energy, infrastructure

- Use case: Learn unified latents for sensor images and structured telemetry, enabling anomaly detection and generative “what-if” diagnostics (decode likely failure modes).

- Tools/workflows: Multi-sensor encoders; simulators that decode from latents to plausible failure signatures.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Need decoders for heterogeneous signals; robust alignment across time series and images.

- Governance and policy: standardizing unified ML pipelines and audits

- Sectors: policy, compliance, risk management

- Use case: Reduce model sprawl by adopting unified backbones; audit shared latents for bias/leakage; standardize alignment metrics as part of model cards.

- Tools/workflows: Latent-space auditing toolkits (coverage, separability, leakage tests); watermarking of generated content.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community consensus on metrics; privacy-by-design practices for strong reconstructors; regulatory acceptance.

- Edge AI and multi-sensor fusion on-device

- Sectors: mobile, IoT, AR/VR

- Use case: Train in the cloud with orange, deploy decoders on-device that sample from Gaussian latents for retrieval, generation, or quick classification; use shared latents for efficient fusion.

- Tools/workflows: Distillation to lightweight decoders; quantized FM approximations for on-device updates; federated embeddings.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Compression/distillation of decoders; limited compute and memory; privacy of local data.

Cross-cutting assumptions and risks

- Generalization beyond images is unproven in this paper; additional work needed for text, audio, video encoders/decoders and their alignment.

- Latent alignment relies on FM-based soft assignments and late-step cutoffs; hyperparameters and numerical stability matter at scale.

- Training overhead is higher than standard encoders due to FM integrals; memory-efficient implementations and batching strategies are important.

- Strong reconstruction improves utility but raises privacy risks; apply privacy safeguards (e.g., DP noise, membership inference tests).

- Domain deployment (e.g., healthcare, autonomous driving) requires rigorous validation, safety cases, and regulatory compliance.

In summary, orange enables immediate, practical gains in image generation quality, representation learning, and joint training, while opening a path to long-term, multimodal unification that could simplify and strengthen ML pipelines across sectors.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.