Synthetic bootstrapped pretraining (2509.15248v1)

Abstract: We introduce Synthetic Bootstrapped Pretraining (SBP), a LLM (LM) pretraining procedure that first learns a model of relations between documents from the pretraining dataset and then leverages it to synthesize a vast new corpus for joint training. While the standard pretraining teaches LMs to learn causal correlations among tokens within a single document, it is not designed to efficiently model the rich, learnable inter-document correlations that can potentially lead to better performance. We validate SBP by designing a compute-matched pretraining setup and pretrain a 3B-parameter model on up to 1T tokens from scratch. We find SBP consistently improves upon a strong repetition baseline and delivers a significant fraction of performance improvement attainable by an oracle upper bound with access to 20x more unique data. Qualitative analysis reveals that the synthesized documents go beyond mere paraphrases -- SBP first abstracts a core concept from the seed material and then crafts a new narration on top of it. Besides strong empirical performance, SBP admits a natural Bayesian interpretation: the synthesizer implicitly learns to abstract the latent concepts shared between related documents.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What is this paper about?

This paper introduces a new way to train LLMs called Synthetic Bootstrapped Pretraining (SBP). The big idea: instead of only learning from single documents, the model also learns from the relationships between different but related documents. It then uses what it learned to write lots of new, high‑quality training text on its own and trains on that too.

Why do this? Because high‑quality internet text is running out, and just repeating the same data over and over stops helping after a point. SBP tries to squeeze more learning out of the data we already have.

What questions did the researchers ask?

In simple terms, they asked:

- Can a model learn not just from what’s inside a single document, but also from how different documents relate to each other (like a research paper and the code that implements it)?

- If we teach a model to understand these relationships, can it write new, useful training text that improves its own learning?

- How much does this help compared to:

- the usual approach (repeating the same data many times), and

- a “best possible” scenario where you get a lot more fresh, unique data?

How did they do it?

First, a quick translation of some terms:

- A LLM learns to predict the next piece of text (token), like supercharged autocomplete.

- Pretraining means teaching the model general language skills by reading lots of text.

- “3B parameters” means the model has about 3 billion adjustable “knobs” it learns to set.

Here’s the SBP method, step by step. Think of it like learning the “core idea” behind two related articles, then writing a fresh article inspired by that idea:

- Step 1: Find related document pairs The system searches the training set for pairs of documents that are semantically similar (for example, a blog post about “Transformers” and a GitHub repo implementing Transformers). This is like finding two books that talk about the same topic from different angles.

- Step 2: Train a “synthesizer” to write B from A The model is trained to generate document B when it’s given document A. In everyday terms: given one text, learn to write a different but related text. This teaches the model to pick up the hidden idea (the “concept”) behind the pair, not just to copy words.

- Step 3: Use the synthesizer to create a big new dataset The system takes real documents from the training set as “seeds,” then uses the synthesizer to write new, related documents. Now you have both real data and a large batch of synthetic (model‑written) data that reflect inter‑document relationships. The model is then trained on both together.

They tested this fairly by “compute‑matching”—keeping the training effort the same across methods. They trained a 3B‑parameter model from scratch on up to 1 trillion tokens (tiny pieces of text), and compared:

- Baseline: repeat the same real data many times

- SBP: real data + synthetic data from the synthesizer

- Oracle: a best‑case that gets much more unique, fresh data

What did they find, and why does it matter?

Here are the main takeaways in plain language:

- SBP beats the standard “just repeat it” approach Across many tests (like reading comprehension and question answering), models trained with SBP performed better than models that simply repeat the same dataset over and over.

- SBP gets a large chunk of the “oracle” improvement without extra real data The oracle has access to way more unique data (about 20× more). SBP captured roughly half of that improvement—without getting any new real data. At smaller scale it got about 42% of the oracle’s gains, and at larger scale about 49%.

- The synthetic documents aren’t just copies or paraphrases Qualitative checks showed the model’s synthetic texts often “abstract the concept” from the seed document and write a different style or angle (for example, turning a personal review into a general guide). That means the model isn’t just rewording—it’s learning the underlying idea and expressing it anew.

- The synthetic data was reasonably high quality

- too much repetition,

- many near‑duplicates,

- factual mistakes,

- being irrelevant to the seed document, and

- copy‑pasting the seed.

The synthetic data had low rates of repetition and duplication and got more factual and more relevant at larger scale. It rarely copied the seed document.

- Training dynamics make sense Early on, SBP can look slightly worse than training on real data (because synthetic data is not perfect). But as training continues, SBP keeps improving while the baseline flattens out, showing the synthetic data adds new learning signals that repeating the same real data can’t provide.

A simple explanation of the “concept” idea

The authors give a helpful statistical view: imagine every document comes from a hidden “concept” (like “espresso techniques” or “Transformer neural networks”). Standard pretraining learns to write good text overall, but it doesn’t explicitly learn to find the hidden concept behind a specific document. SBP’s synthesizer does: given one document, it guesses the hidden concept and writes a new document based on that concept. Training on these new documents helps the model capture concept‑level knowledge that normal training might miss.

It’s like reading one article about climate change, figuring out the core idea, then writing a different piece (say, a Q&A or a history summary) using that core idea—this strengthens understanding.

Why is this important?

- Better use of limited high‑quality data The internet’s best text is finite. SBP helps models learn more from what we already have by uncovering and using inter‑document relationships.

- Less dependence on giant “teacher” models Many synthetic‑data methods rely on a bigger, human‑aligned model to generate training data. SBP learns its synthesizer directly from the same dataset, so improvements come from smarter use of the data—not from borrowing another model’s knowledge.

- Practical gains at large scale SBP was tested with a 3B model and up to 1 trillion training tokens—a scale that matters in real model development. The consistent improvements suggest it could help future large models trained under data limits.

- A path past the “data scaling wall” As simply “adding more data” becomes harder, methods like SBP that amplify the value of existing data could keep LLMs improving.

In short: SBP teaches models to learn the hidden concepts that connect documents, use that to write new, useful training text, and then get better by training on both real and synthetic data. It’s a promising way to keep improving LLMs even when fresh, high‑quality data is scarce.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper—framed to be actionable for future research.

- Pairing mechanism reproducibility: the ANN/embedding model used for document similarity is not specified; sensitivity to embedding choice, normalization, and indexing hyperparameters is unknown.

- Pairing hyperparameters: no ablation on similarity threshold α, neighbor count per document, or directional pairing (which doc is seed vs target), and their impact on synthesizer quality and downstream performance.

- Retrieval quality metrics: precision/recall of nearest-neighbor pairing across domains and languages is not evaluated; the rate and consequences of false positives (irrelevant pairs) remain uncertain.

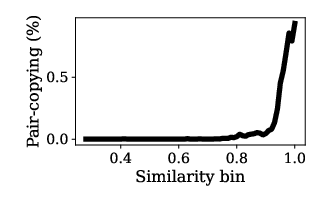

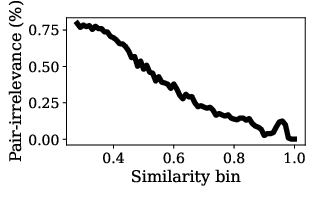

- Noise-robust objectives: given non-trivial pair-irrelevance (25.6%→7.8%), there is no exploration of robust training (e.g., pair weighting, denoising, contrastive or max-margin loss) to mitigate noisy pairs.

- Seed selection policy: seeds are sampled uniformly from Dpre; no study of weighting by topic rarity, document quality, length, or recency to improve synthesis diversity and relevance.

- Generation hyperparameters: temperature, top-k/p, and sampling strategies for synthetic text are not reported; their effects on diversity, factuality, and downstream gains are unquantified.

- Synthetic-real mixture ratio: only two mixture points are reported (e.g., ~37.5% synthetic at 200B); there is no general guidance or curriculum schedule across scales and domains.

- Iterative synthesis: SBP uses single-pass synthesis; effects of multi-round synthesis (synthesize→retrain→resynthesize) on quality, stability, and potential collapse are unexplored.

- Deduplication across real/synthetic: policies to prevent near-duplicates across Dpre and Spre are not detailed; impact of cross-set dedup on training efficiency is unknown.

- Long-context exclusion: capping documents at ≤4,096 tokens for pretraining (and ≤8,192 for pairing) filters out long documents; the effect on long-context capabilities and inter-document modeling is not measured.

- Domain coverage: results focus on English web text and general QA/perplexity; performance on coding, math reasoning, scientific writing, legal text, and multilingual corpora is untested.

- Baseline breadth: no controlled comparison against (i) teacher-synthesized corpora, (ii) retrieval-augmented pretraining in-context, or (iii) auxiliary conditional/pair losses without data synthesis.

- Oracle construction: the 1T oracle uses only 482B unique tokens; how tight this is as an upper bound is unclear—alternative or teacher-based oracles could better contextualize SBP gains.

- Statistical reliability: improvements lack confidence intervals, multiple seeds, or variance estimates; stability and reproducibility of SBP gains are unverified.

- Contamination audits: potential train-test leakage into benchmarks is not assessed; effect of contamination on reported gains is unknown.

- Factuality controls: synthetic data has high non-factual rates (15.1% at 200B, 8.7% at 1T vs 1.8% real); mechanisms to improve factuality (e.g., calibration, retrieval grounding, verification) are not investigated.

- Safety/bias/PII: toxicity, bias amplification, and privacy leakage risks in synthetic data are not measured; filters and redaction policies are unspecified.

- Efficiency accounting: net compute cost for synthesizer-tuning and generation vs end-task gains (accuracy-per-FLOP or per-token) is not quantified.

- Model scaling: behavior beyond 3B (and briefly 6B in appendix) is not characterized; whether SBP gains persist, saturate, or change at larger model sizes and longer training durations is unknown.

- Architecture interactions: the effect of QK-norm or other stabilization tweaks on results is not isolated; whether gains are attributable to SBP vs architecture/training changes is unclear.

- Concept posterior validation: the Bayesian interpretation remains qualitative; empirical tests proving the synthesizer performs posterior concept inference (with measurable proxies) are missing.

- Conditioning granularity: only full-document→document conditioning is explored; alternatives (e.g., summaries, outlines, extracted concepts, section-level conditioning) could improve relevance and controllability.

- Topic distribution drift: how synthesis alters topic/style distributions (e.g., over-representing frequent or “easy” topics) is not analyzed; mechanisms to maintain corpus balance are absent.

- Multilingual retrieval: inner-product similarity on a unit sphere may degrade across languages; cross-lingual pairing quality and its impact on synthesis are unstudied.

- Interaction with alignment: downstream effects on instruction tuning, RLHF, tool use, and agentic behaviors are unknown; does SBP pretraining help or hinder alignment objectives?

- RAG integration: a quantitative comparison of encoding inter-document relations via synthesis (SBP) vs context-time retrieval (RAG) is missing; hybrid approaches remain unexplored.

- Training dynamics and forgetting: potential for catastrophic forgetting or distribution shift during joint training with synthetic data is not assessed; optimal scheduling and regularization remain open.

- Release and reproducibility: code, models, pairing indices, and synthetic corpora are not indicated as available; external validation and adoption are limited without artifacts.

Glossary

- Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) methodology: An indexing and search technique for efficiently finding similar items in high-dimensional spaces. "we adopt the Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) methodology \citep{malkov2018efficientrobustapproximatenearest}, which embeds each document as a quantized vector normalized to the unit sphere and then performs massively parallelizable linear algebraic operations."

- ARCâChallenge: A hard multiple-choice science QA benchmark used to evaluate reasoning abilities. "Hard scientific reasoning with ARCâChallenge~\citep{clark2018think};"

- ARCâEasy: An easier multiple-choice science QA benchmark for assessing factual and basic reasoning skills. "Easy scientific reasoning with ARCâEasy~\citep{clark2018think};"

- Bayes' rule: A fundamental theorem relating conditional and marginal probabilities, used for inferring posterior distributions. "Here, we use Bayes' rule and the conditional independence assumption"

- Bayesian hierarchical concept model: A probabilistic framework where documents are generated from latent shared concepts organized hierarchically. "We formalize this intuition through a Bayesian hierarchical concept model, where documents are related through shared concepts."

- BPE tokenization: Byte Pair Encoding; a subword tokenization method that builds a vocabulary of frequent character sequences. "we implement a customized BPE tokenization with a vocabulary size of 49{,}152."

- Compute-matched: An experimental setup that controls and equalizes training compute (e.g., tokens or FLOPs) across methods for fair comparison. "We propose a compute-matched experimentation framework to rigorously compare SBP against two natural references"

- Conditional independence: An assumption that two variables are independent given a third variable (e.g., documents independent given a concept). "Here, we use Bayes' rule and the conditional independence assumption"

- Conditional probability: The probability of an event given that another event has occurred; here modeling one document given another. "maximizing the conditional probability of $\doctwo$ given $\docone$"

- Context window: The maximum number of tokens the model processes at once. "we cap the context window of the synthesizer-tuning \eqref{eqn:synthesizer-objective-lm} step at 8{,}192 tokens."

- Cosine learning rate scale: A scheduling strategy that adjusts the learning rate following a cosine curve over training. "We apply a cosine learning rate scale with a 5\% warmup to a peak learning rate of 1e-2, followed by subsequent decay to 5e-5 towards the end."

- Data-constrained setup: A training scenario where only a fixed amount of data is available, emphasizing efficient use of limited corpora. "We consider a data-constrained setup where the goal is to train the best-performing LM given access to a fixed document collection"

- Data synthesizer: A model that generates new documents related to seed documents by learning inter-document relations. "creating a ``data synthesizer'' that can synthesize a new, related document given a seed document."

- De-duplicated dataset: A corpus processed to remove duplicate documents to increase the amount of unique content. "we begin with the de-duplicated dataset, which consists of 769B tokens."

- Entropy: A measure of randomness or diversity in model outputs; higher entropy implies more varied generations. "encouraging the synthesizer to produce diverse, high-entropy outputs rather than deterministic synthesis."

- Few-shot prompts: Evaluation or training where the model is given a small number of examples within the prompt. "We directly evaluate the pretrained model with either zero-shot or few-shot prompts."

- Grouped Query Attention: An attention mechanism variant where query heads are grouped to improve efficiency or performance. "Each layer employs grouped query attention with 24 query heads and 8 key/value heads."

- Hierarchical sampling process: A multi-level sampling procedure, e.g., sampling a seed document and then a conditioned document. "Finally, SBP synthesizes $\Spre$ through a hierarchical sampling process:"

- Inner-product similarity: A similarity measure computed as the dot product between embedding vectors. "we use inner-product similarity, which we denote by $\<\docone, \doctwo\>$."

- Jaccard similarity: A set-based similarity metric defined as intersection over union, used to detect near-duplicates. "determined by Jaccard similarity at a threshold of 0.6"

- LAMBADA: A benchmark focused on narrative understanding and predicting a word given a broad context. "Narrative understanding with LAMBADA~\citep{paperno2016lambada}."

- Latent concepts: Unobserved underlying ideas or themes that generate related documents. "the synthesizer implicitly learns to abstract the latent concepts shared between related documents."

- LM-as-judge: Using a LLM to automatically evaluate generated texts against criteria (e.g., relevance, copying). "Operationally, we implement Repetition, Pair-irrelevance, and Pair-copying using LM-as-judge"

- Log-likelihood: The logarithm of the probability assigned by a model to observed data; commonly maximized in training. "maximizing the sum of the log-likelihood of pretraining documents"

- Marginal distribution: The distribution of a subset of variables (e.g., documents) regardless of other variables (e.g., concepts). "attempts to learn this marginal distribution."

- Marginal likelihood: The probability of observed data integrated over latent variables (e.g., concepts). "the pretraining objective models the marginal likelihood of documents:"

- MMLU: A broad, multi-task multiple-choice benchmark covering many academic subjects. "Broad domain multiple-choice with MMLU~\citep{hendrycks2020measuring}."

- Next-token prediction: The autoregressive objective of predicting the next token in a sequence. "using next-token prediction as the pretraining objective"

- OpenWebText2: A public web-text corpus used to evaluate or train LLMs. "OpenWebText2 from EleutherAI~\citep{gpt2}"

- Oracle upper bound: A reference model trained with access to much more unique data, used to contextualize achievable gains. "we also evaluate an oracle upper bound with unlimited data access."

- Perplexity: A measure of how well a probabilistic model predicts a sample; lower is better. "We evaluate held-out test perplexity (exponential of negative log-probability) on"

- Posterior inference: Estimating the distribution of latent variables given observed data. "the synthesizer must first perform posterior inference to infer the latent concept given the document $\docone$"

- Prenorm: A transformer design where layer normalization is applied before attention and feedforward blocks. "we apply prenorm to both the attention and FFN blocks."

- QK-norm: A normalization technique applied to query and key projections to stabilize attention training. "implementing a QK-norm on top of the existing design, which we empirically find to stabilize training."

- Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG): A method that augments generation by retrieving external documents relevant to the input. "retrieval augmented generation (RAG) \citep{Lample:2019, rag}"

- RoPE: Rotary positional embeddings; a positional encoding method that rotates embeddings to encode token positions. "The position embedding is RoPE \citep{rope} for queries and keys, with frequency 5e+5."

- Synthesizer-tuning: Training the conditional generator to produce a related document given a seed document. "We refer to this step as ``synthesizer-tuning'' as we are training a conditional probabilistic model that synthesizes a related $\doctwo$ from a given $\docone$."

- WebQS: A web-based question-answering benchmark (WebQuestions). "Openbook QA with WebQS~\citep{berant-etal-2013-semantic};"

- Winogrande: A commonsense reasoning benchmark requiring pronoun resolution and contextual understanding. "Common sense reasoning with Winogrande~\citep{sakaguchi2021winogrande};"

- Zero-shot: Evaluation or generation without any in-context examples provided. "We directly evaluate the pretrained model with either zero-shot or few-shot prompts."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.