- The paper introduces FE2E, a dense geometry estimator that leverages the inherent structural priors of editing models for stable and efficient performance.

- The methodology incorporates a consistent velocity training objective and logarithmic quantization to enable accurate joint estimation of depth and surface normals.

- Empirical results demonstrate significant improvements, such as a 35% AbsRel gain on ETH3D and high performance using only 0.2% of conventional training data.

From Editor to Dense Geometry Estimator: A Technical Analysis

Introduction

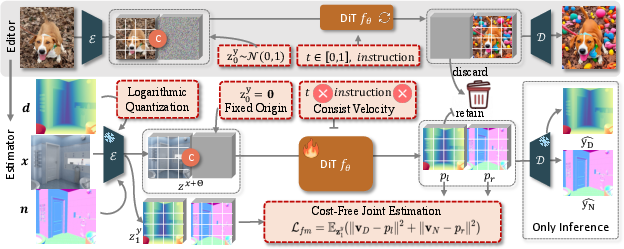

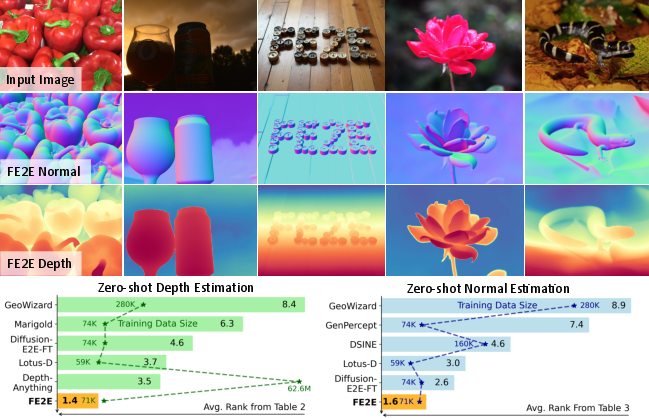

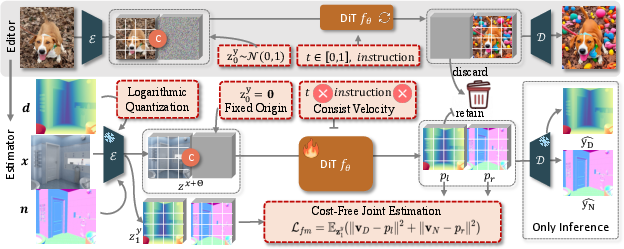

This work introduces FE2E, a foundation model for monocular dense geometry prediction that leverages a Diffusion Transformer (DiT)-based image editing model as its backbone. The central hypothesis is that image editing models, as opposed to text-to-image (T2I) generative models, provide a more suitable inductive bias for dense prediction tasks such as depth and surface normal estimation. The authors systematically analyze the fine-tuning dynamics of both editing and generative models, demonstrating that editing models possess inherent structural priors that facilitate more stable convergence and superior performance. FE2E is constructed by adapting the Step1X-Edit editor, introducing a consistent velocity training objective, logarithmic quantization for high-precision supervision, and a cost-free joint estimation mechanism for depth and normals. The model achieves state-of-the-art (SoTA) zero-shot performance on multiple benchmarks, outperforming data-intensive models with orders of magnitude less supervision.

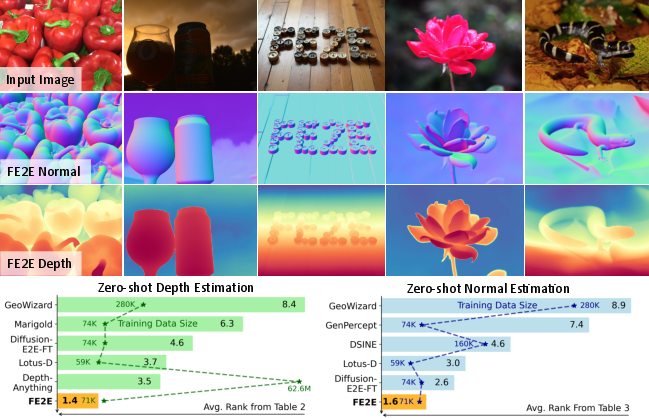

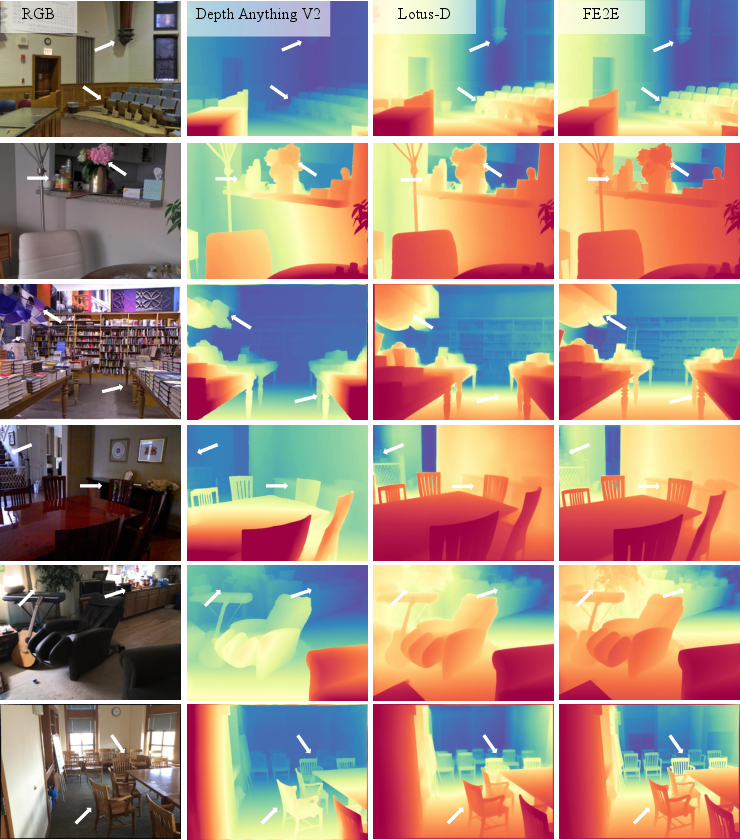

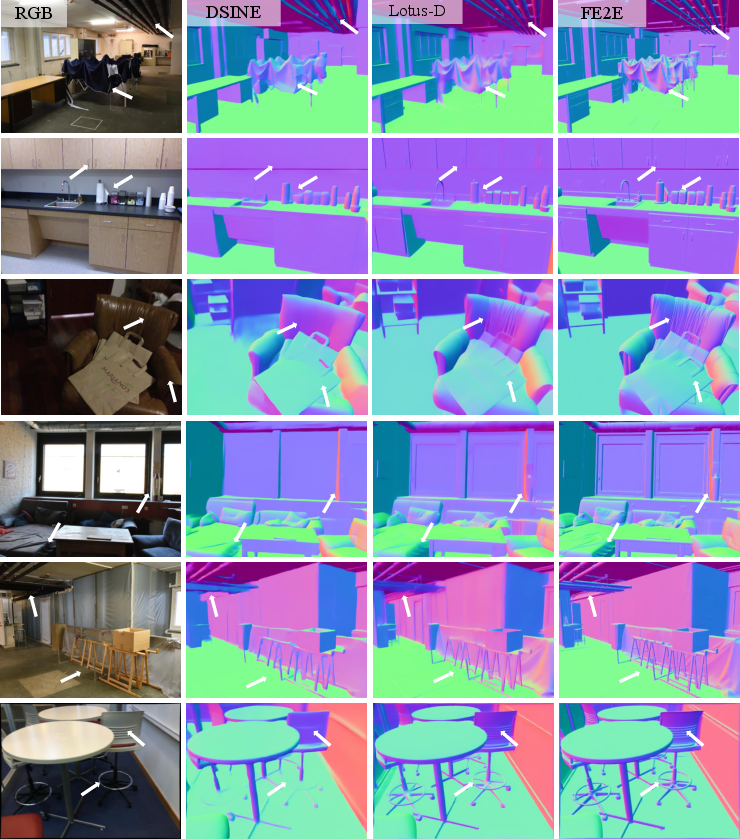

Figure 1: FE2E, a DiT-based foundation model for monocular dense geometry prediction, achieves top average ranking across multiple datasets for zero-shot depth and normal estimation, even with limited training data.

Motivation and Analysis of Editing vs. Generative Models

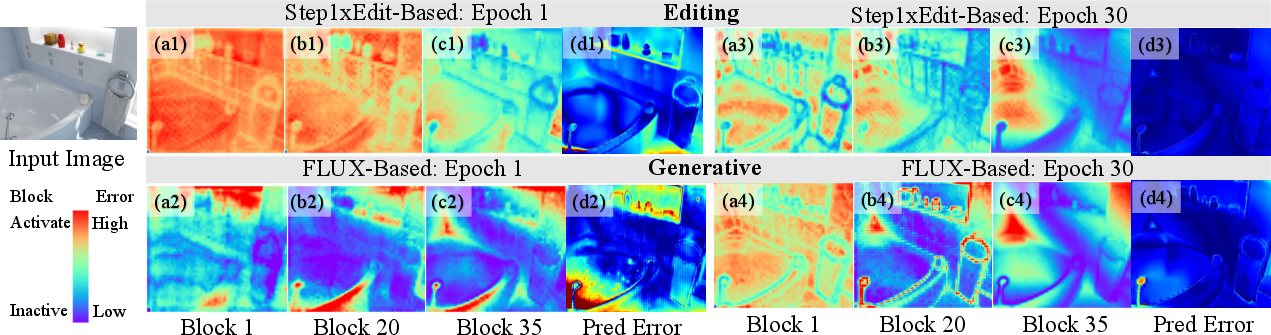

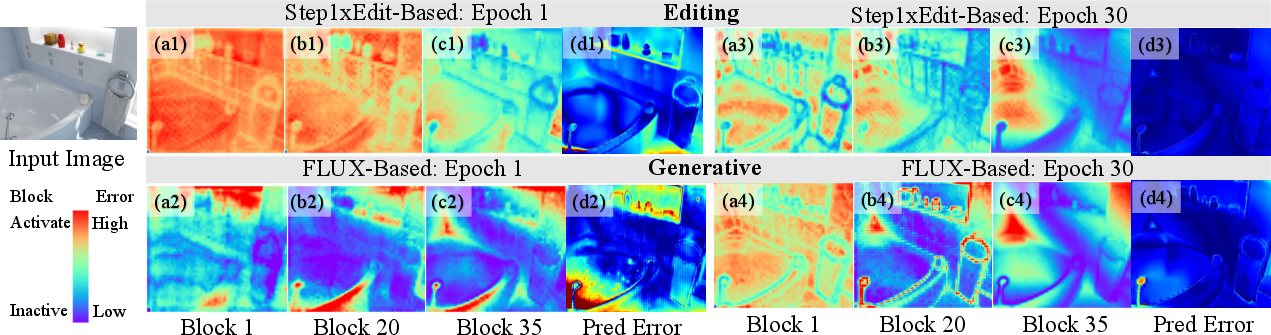

The authors argue that dense geometry prediction is fundamentally an image-to-image (I2I) task, making image editing models a more natural fit than T2I generative models. Through a comparative analysis of Step1X-Edit (editor) and FLUX (generator), both based on the DiT architecture, three key findings are established:

- Superior Inductive Bias: Editing models exhibit feature activations that are already aligned with geometric structures at initialization, whereas generative models require substantial feature reshaping during fine-tuning.

- Stable Convergence: Editors demonstrate smoother and more stable loss curves during training, while generators exhibit oscillatory behavior and hit a convergence bottleneck.

- Performance Ceiling: Generative models are unable to close the performance gap, even after extensive fine-tuning, due to their less suitable priors for dense prediction.

Figure 2: Feature evolution in DiT-based generative and editing models during fine-tuning, showing that editors refine pre-existing geometric features while generators require substantial restructuring.

This analysis justifies the paradigm shift from generative to editing models for dense geometry estimation.

FE2E Architecture and Training Protocol

Model Adaptation

FE2E adapts the Step1X-Edit editor for deterministic dense prediction by:

- Reformulating the Training Objective: The original flow matching loss, designed for stochastic editing, is replaced with a consistent velocity objective. This eliminates the need for stochastic sampling and aligns the optimization with the deterministic nature of dense prediction.

- Logarithmic Quantization: To address the precision mismatch between BF16 (native to editing models) and the high-precision requirements of depth estimation, logarithmic quantization is employed. This ensures uniform relative error across the depth range, avoiding the pitfalls of uniform or inverse quantization.

Figure 3: FE2E adaptation pipeline, illustrating VAE encoding, DiT-based velocity prediction, and joint depth/normal estimation in latent space.

Cost-Free Joint Estimation

FE2E exploits the DiT's global attention mechanism to jointly estimate depth and surface normals in a single forward pass. By supervising both output regions of the DiT, mutual information exchange is enabled without additional computational cost, leading to synergistic improvements in both tasks.

Empirical Results

Zero-Shot Depth and Normal Estimation

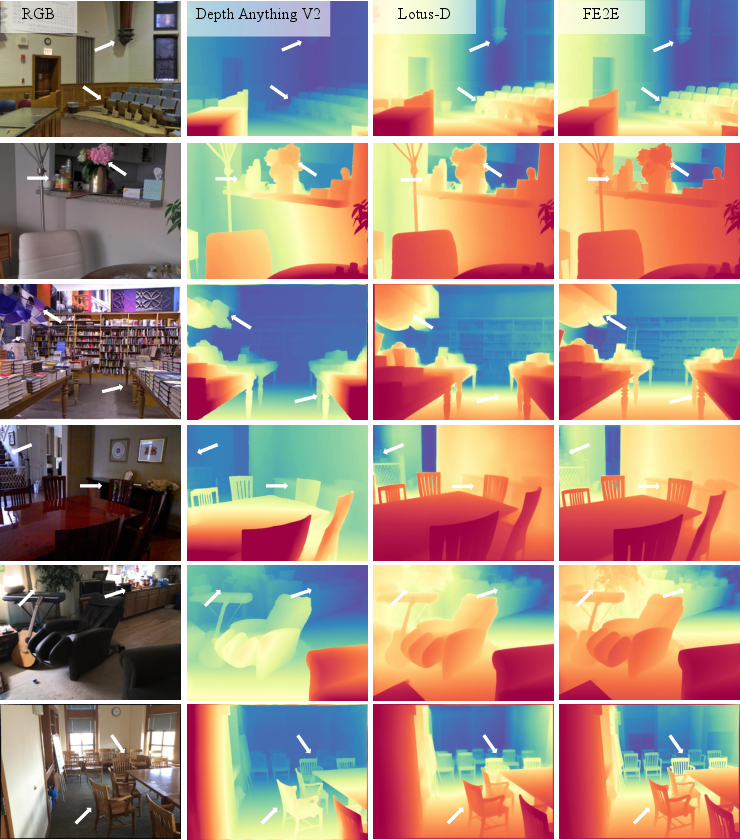

FE2E achieves SoTA results on five standard benchmarks for zero-shot affine-invariant depth estimation and four benchmarks for surface normal estimation. Notably, it delivers:

- 35% AbsRel improvement on ETH3D and 10% on KITTI over the next best method.

- Superior average ranking compared to DepthAnything, despite using only 0.071M training images versus 62.6M.

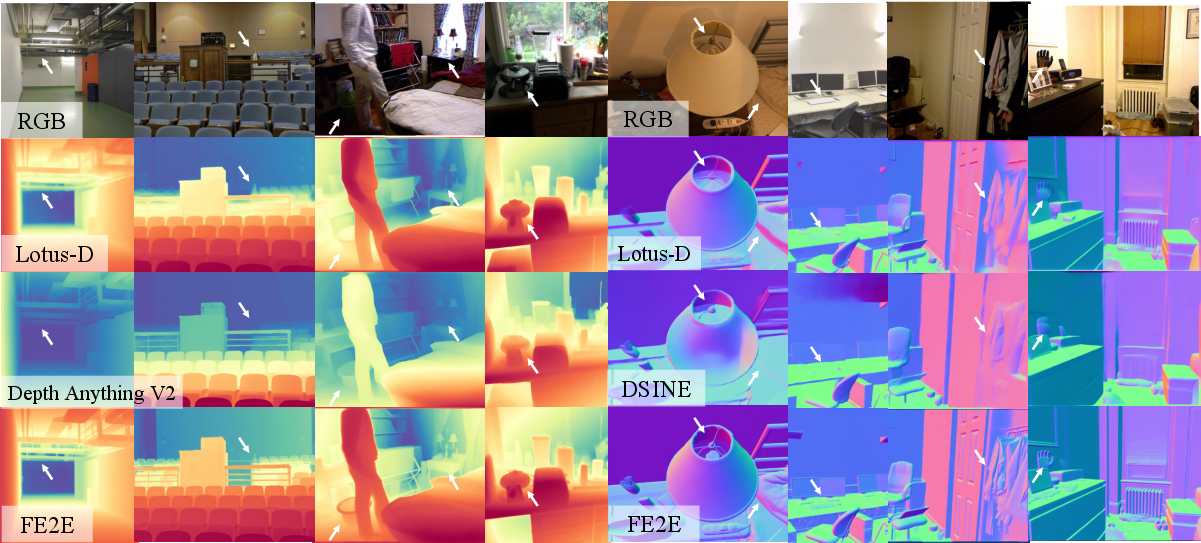

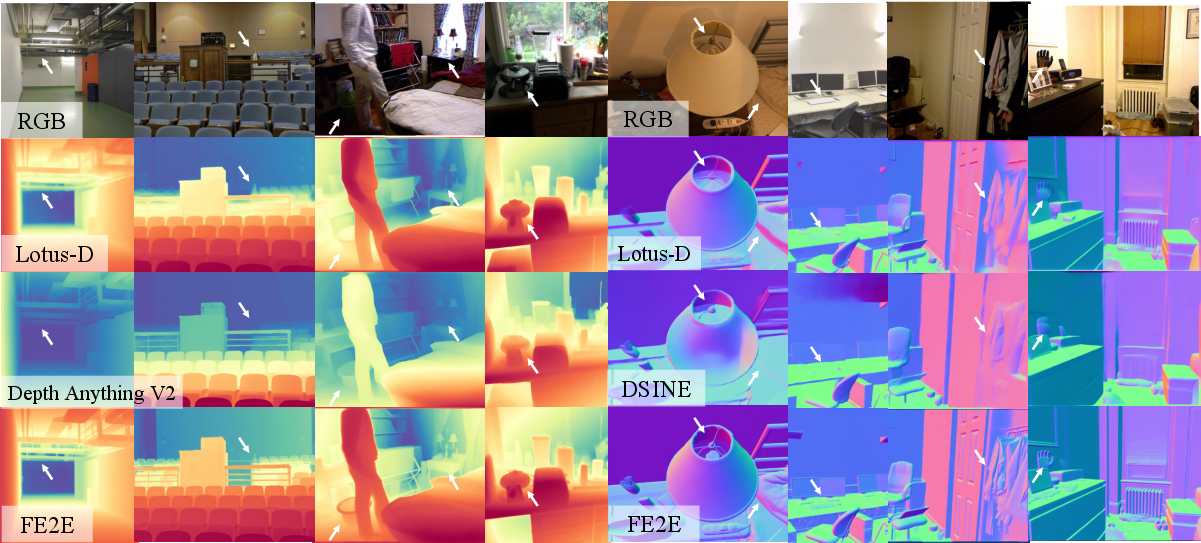

Figure 4: Quantitative comparison on zero-shot depth and normal estimation, with FE2E predictions showing improved accuracy in challenging regions.

Figure 5: Qualitative comparison on zero-shot affine-invariant depth estimation, highlighting FE2E's accuracy in structurally complex regions.

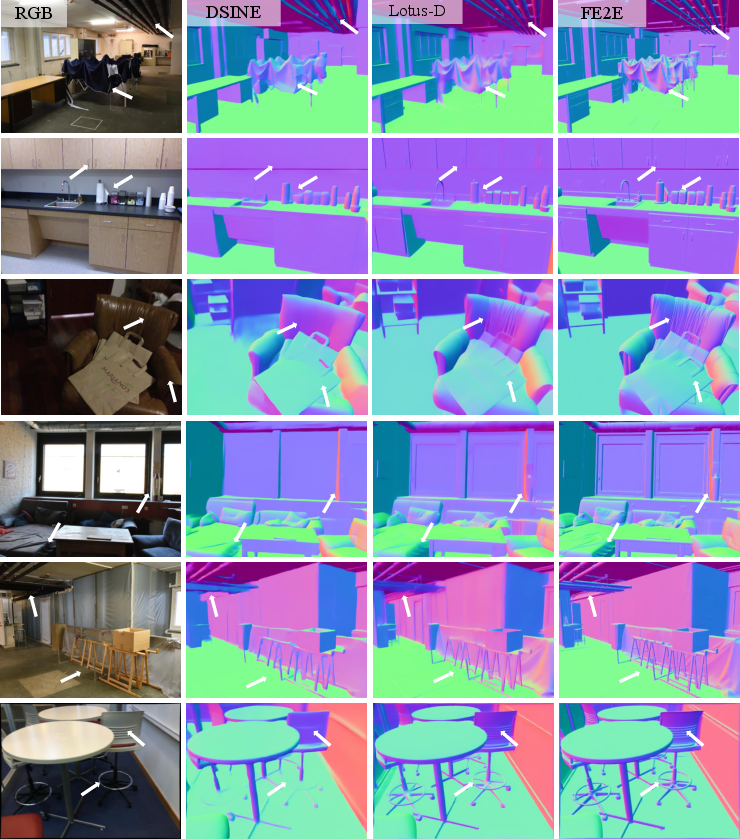

Figure 6: Qualitative comparison on zero-shot surface normal estimation, demonstrating FE2E's ability to recover fine geometric details.

Ablation Studies

Ablations confirm the contribution of each component:

- Consistent velocity training reduces inference error and accelerates convergence.

- Logarithmic quantization yields uniform relative error, critical for high-precision tasks.

- Joint estimation further improves both depth and normal predictions, especially in complex scenes.

Implementation Considerations

- Resource Requirements: FE2E can be trained on a single RTX 4090 GPU, with full training (30 epochs) completed in ~1.5 days on NVIDIA H20 GPUs.

- Data Efficiency: The model achieves SoTA with only 0.2% of the geometric ground truth data used by data-driven baselines.

- Precision Handling: Logarithmic quantization is essential for maintaining accuracy under BF16 constraints.

- Scalability: While FE2E is more computationally intensive than some self-supervised approaches, it offers a favorable trade-off between performance and efficiency.

Implications and Future Directions

The findings have several implications:

- Paradigm Shift: The work establishes editing models as a superior foundation for dense prediction, challenging the prevailing reliance on T2I generative models.

- Data Efficiency: Leveraging editing priors enables high performance with minimal supervision, which is critical for domains with limited labeled data.

- Unified Prediction: The cost-free joint estimation mechanism suggests a path toward unified geometric prediction frameworks.

Future research may explore:

- Scaling to Larger Editing Models: Incorporating more advanced or larger-scale editing models could further improve performance.

- Extending to Other Dense Prediction Tasks: The FE2E paradigm may generalize to tasks such as semantic segmentation or optical flow.

- Optimizing Computational Efficiency: Reducing inference latency and memory footprint will be important for deployment in real-time or resource-constrained settings.

Conclusion

FE2E demonstrates that image editing models, when properly adapted, provide a more effective and data-efficient foundation for dense geometry estimation than generative models. The consistent velocity training objective, logarithmic quantization, and cost-free joint estimation collectively enable SoTA zero-shot performance across multiple benchmarks. This work substantiates the "From Editor to Estimator" paradigm and opens new avenues for leveraging editing priors in dense prediction tasks.