Growth Forms of Tilings (2508.19928v1)

Abstract: The growth form (or corona limit) of a tiling is the limit form of its coordination shells, i.e. its set of tiles located at a fixed distance from some tile. We give an overview of current results, conjectures and open questions about growth forms, including periodic, multigrid, substitution, and hat tilings.

Summary

- The paper introduces a rigorous method for computing growth forms, showing that periodic tilings yield convex, centrosymmetric polytopes.

- It employs grid and cut-and-projection methods to derive explicit formulas for the growth forms of Penrose and Ammann tilings.

- The study reveals unresolved challenges in substitution tilings, suggesting the possibility of fractal or nonconvex growth forms and highlighting algorithmic complexity.

Growth Forms of Tilings: A Comprehensive Analysis

Introduction and Motivation

The concept of growth forms in tiling theory provides a geometric and combinatorial framework for understanding the large-scale structure of tilings, particularly through the scaling limits of coordination shells. While growth forms for periodic tilings are well-characterized as convex, centrosymmetric polytopes, the situation for aperiodic and substitution tilings remains largely unresolved. This paper systematically surveys known results, introduces new computational and experimental findings, and highlights open problems, especially in the context of substitution and aperiodic tilings.

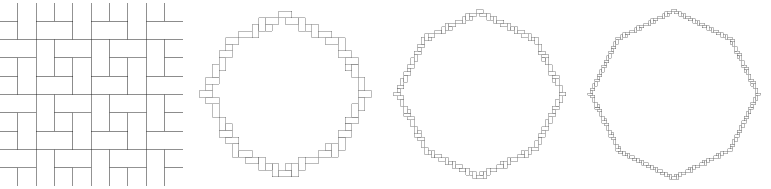

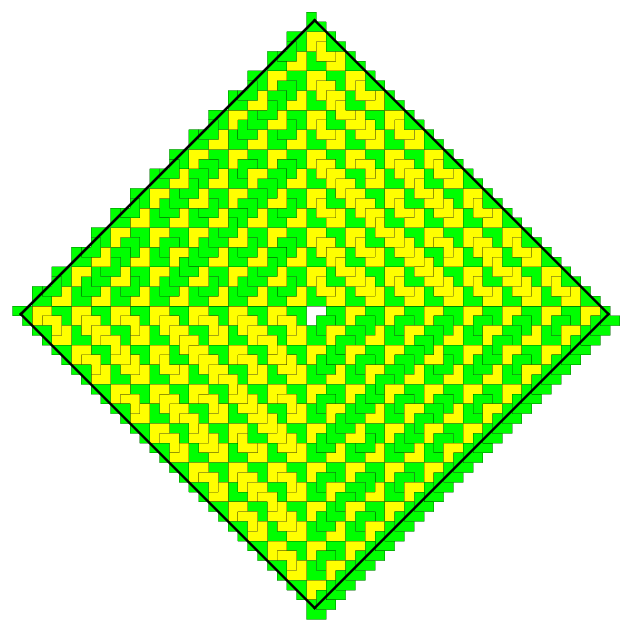

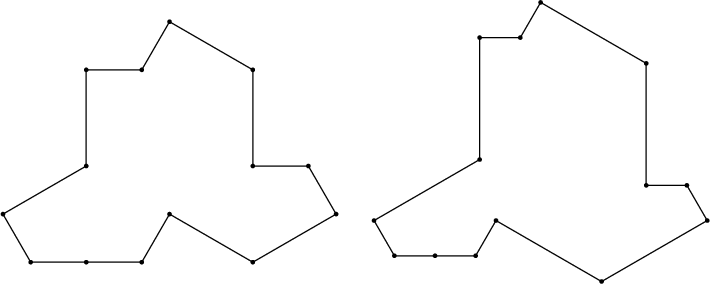

Figure 1: Tiling, scaled coordination shells P8,P16,P24, illustrating the emergence of a limiting growth form.

Growth Forms in Periodic Tilings

Periodic tilings, defined via lattice translations and a finite set of fundamental tiles, admit a complete characterization of their growth forms. The main result is that every periodic tiling possesses a growth form that is a convex, centrosymmetric polytope. The computation of the growth form is algorithmic: one identifies fundamental tiles, computes coordination shells, and determines the convex hull of normalized translation vectors associated with shell membership.

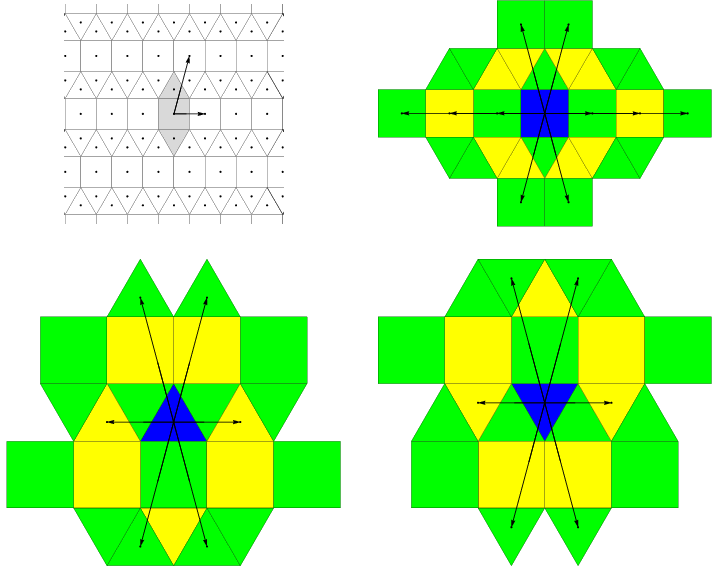

Figure 2: Top left: Tiling, fundamental tiles (grey), lattice, and translation vectors. Others: Fundamental tiles (blue) with z=3 coordination shells and vectors v.

Figure 3: Left: Vectors w and growth form. Right: Growth form, patch P0 (white), 12-corona scaled, odd coordination shells green, even ones yellow.

The convergence to the growth form can be slow near certain vertices, a phenomenon observed in both periodic and aperiodic settings. The growth form is independent of the initial patch, a property that follows from the underlying translation symmetry.

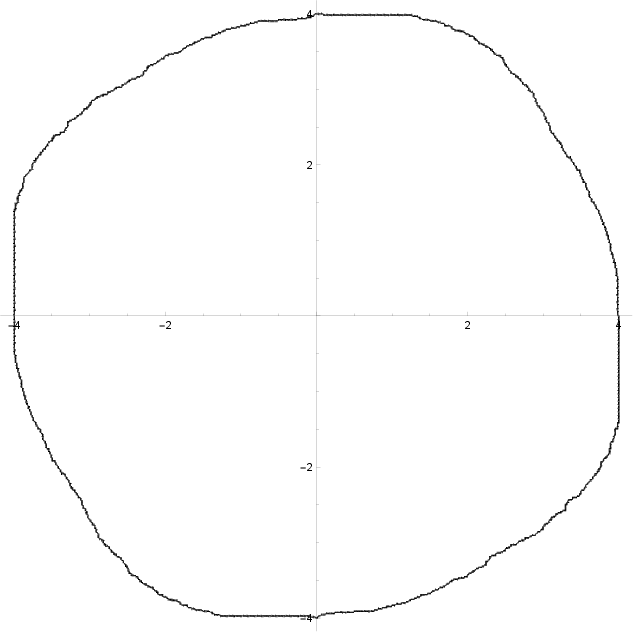

Grid Tilings and Cut-and-Projection Methods

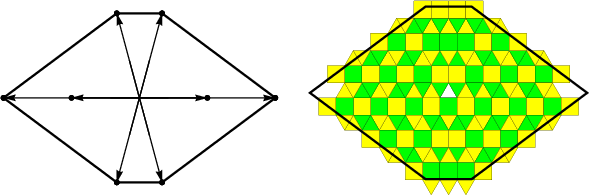

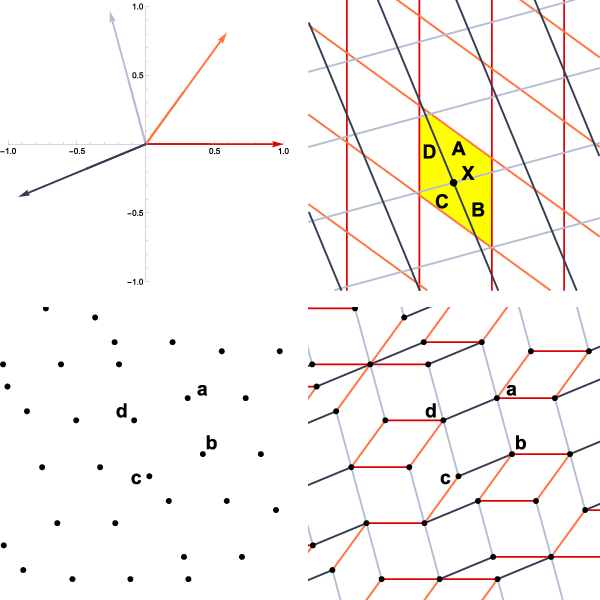

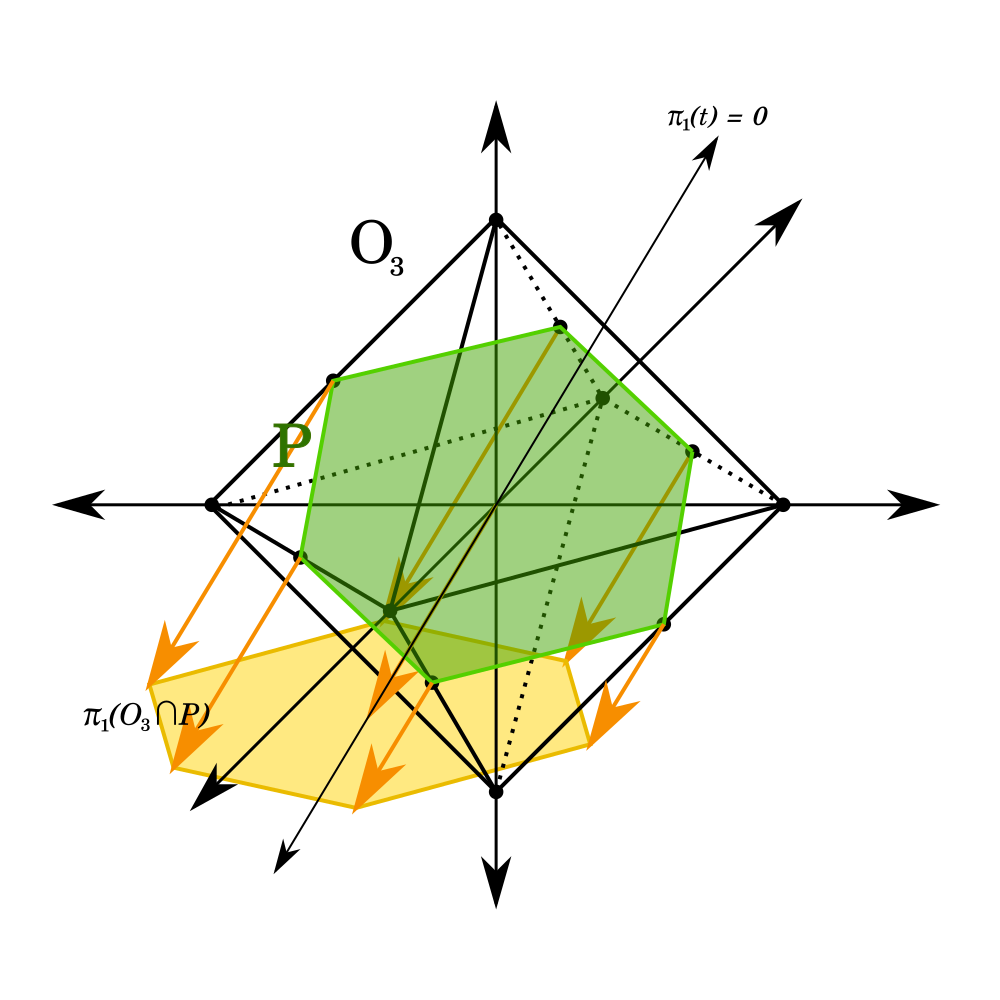

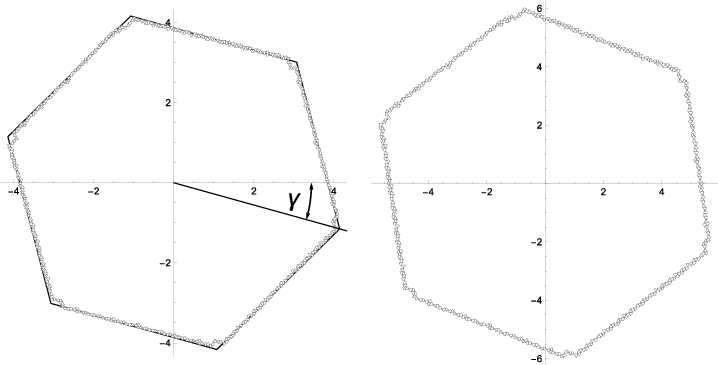

Grid tilings, including those arising from cut-and-projection methods (e.g., Penrose and Ammann tilings), are analyzed via the dualization of multigrids. The growth form in this context is given by the projection of the N-dimensional cross-polytope onto the physical space, intersected with the appropriate subspace. Explicit formulas for the vertices of the growth form are derived in both two and three dimensions, involving combinatorial data from the grid vectors.

Figure 4: Construction of a grid tiling: top left: grid vectors gi; top right: 4-grid LN with intersection point X; adjacent tiles A, B, C, D; bottom left: vertices Λ of the dual tiling; bottom right: edges of dual tiling.

Figure 5: Example of finding the growth form for a case where N=3, d=2.

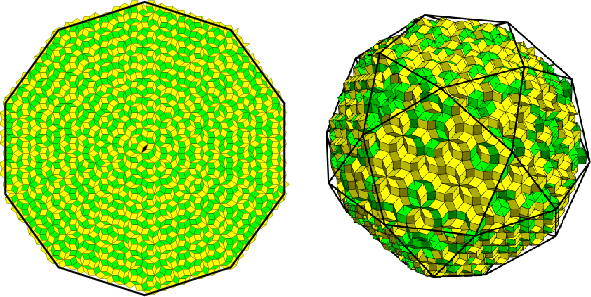

Figure 6: Growth forms and scaled n-coronas, left: Penrose tiling, n=29; right: Ammann 3D tiling, n=19.

For Penrose tilings, the growth form is a regular decagon, while for the Ammann 3D tiling, it is an icosidodecahedron. These results are robust and rely on the regularity of the underlying grid; nonregular grids can yield nonconvex growth forms, an area that remains underexplored.

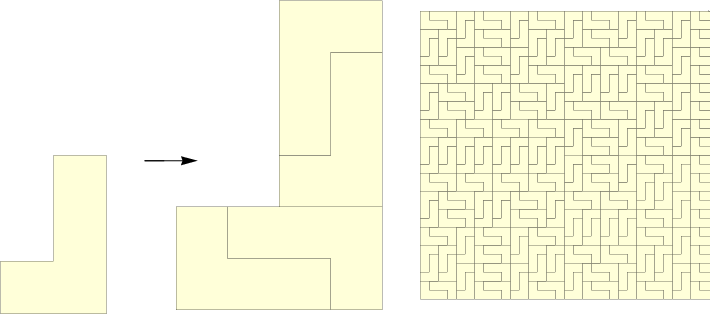

Substitution Tilings: Chair, L-Tetromino, and Open Problems

Substitution tilings, constructed via inflation and dissection rules, present significant challenges. The existence and computation of growth forms in this class are unresolved in general, with only a few cases fully understood.

Chair Tiling

The chair tiling, a classic example, is shown to have a growth form identical to that of the periodic square lattice. This is established by constructing a dual graph and demonstrating that the addition of diagonals does not affect geodesic distances.

Figure 7: Chair tiling. Left: prototiles, inflation and dissection; right: tiling.

Figure 8: Dual tiling to chair tiling. left: prototile; right: tiling and dual tiling.

Figure 9: Scaled coordination shells P1 to P15 of the chair tiling, growth form.

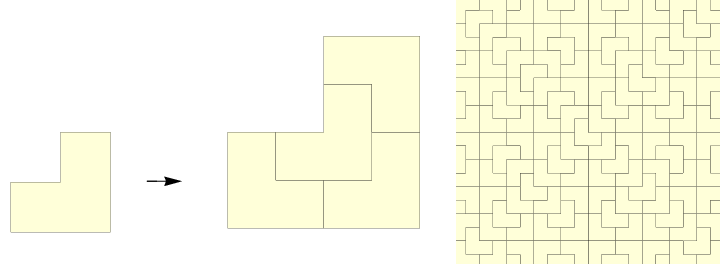

L-Tetromino Tiling

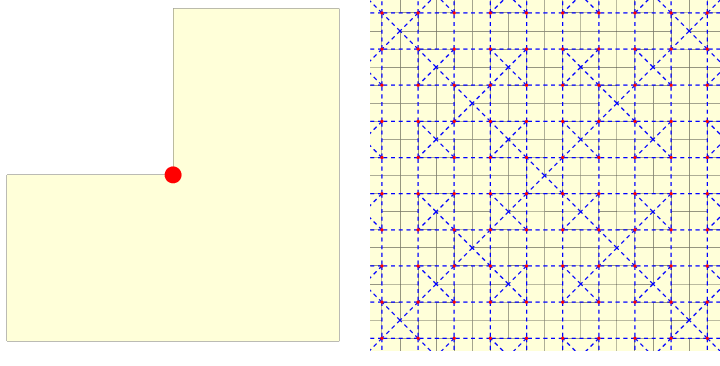

For the L-tetromino tiling, computational experiments suggest that the growth form is not a polygon, a claim that, if confirmed, would contradict the expectation that growth forms are always polytopal in substitution tilings.

Figure 10: L tetromino tiling, left: prototiles, inflation and dissection, right: tiling.

Figure 11: L-tetromino tiling, scaled coordination shell P255, 1651 tiles.

This observation raises the possibility of more exotic growth forms, potentially with fractal boundaries, although the authors conjecture that growth forms must be star bodies.

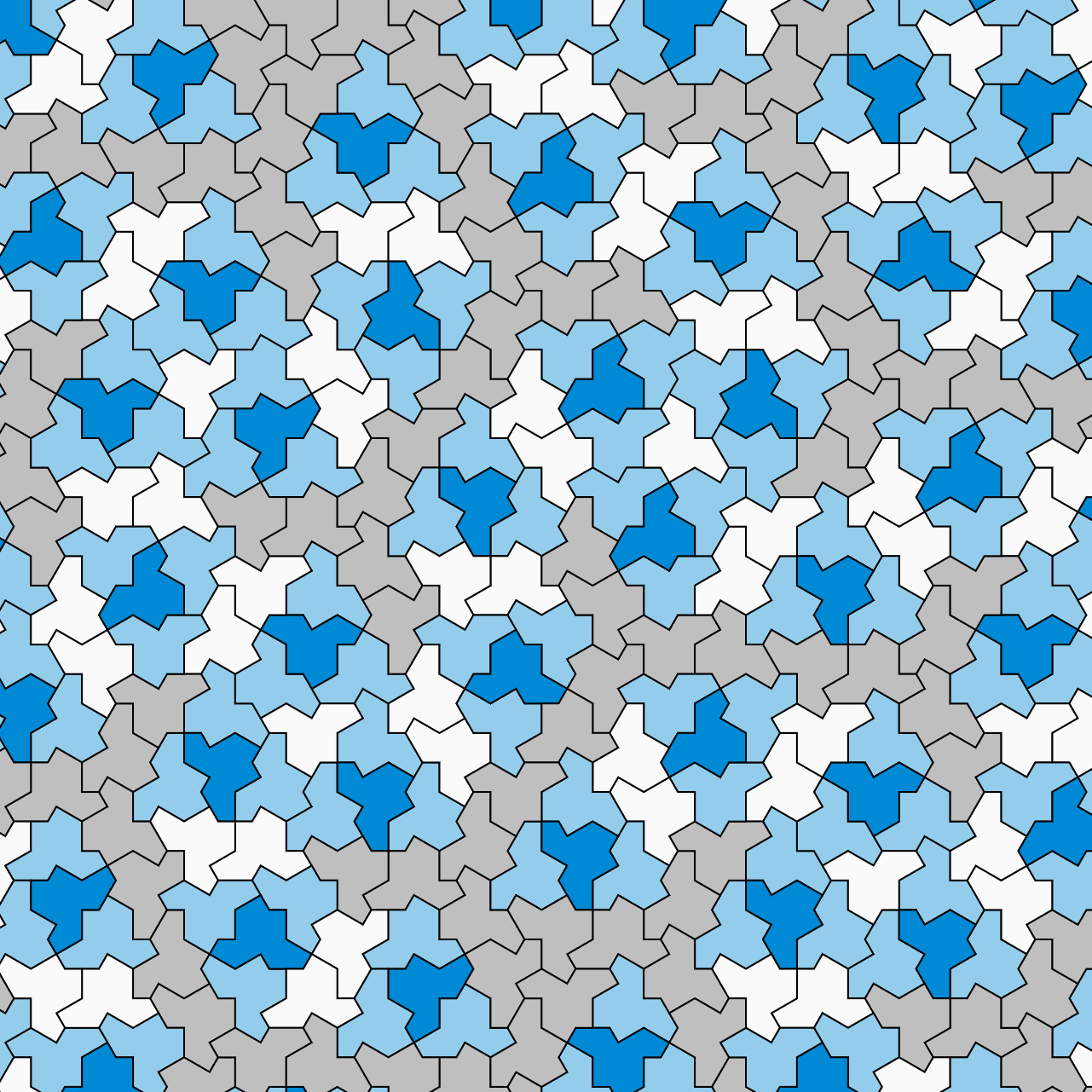

Hat Tiling and Related Structures

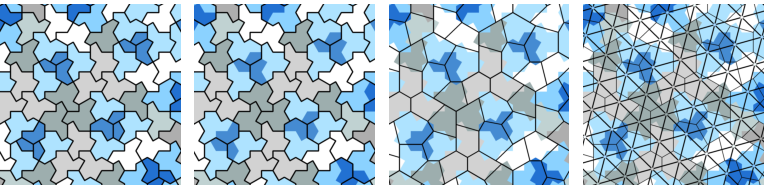

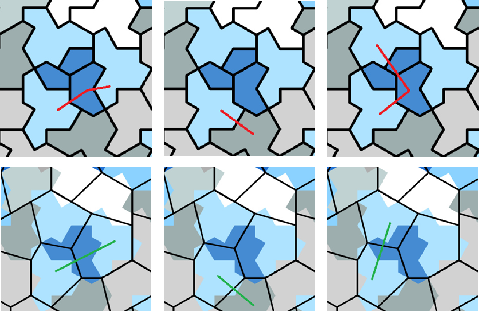

The hat tiling, a recent solution to the "Ein stein" problem, is shown to have a regular hexagon as its growth form. The proof leverages a metatile structure and dualization arguments, reducing the problem to the well-understood case of the hexagonal lattice.

Figure 12: Hat tiling.

Figure 13: Tiles: Hat and Tile(1,3).

Figure 14: Left: Growth from Hat tiling, scaled shell P55. Right: scaled shell P55 from Tile(1,3); note the different scales.

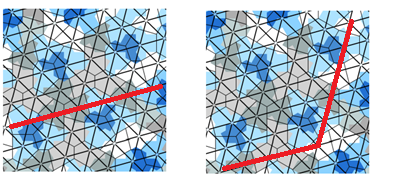

The authors conjecture explicit formulas for the area and edge lengths of the growth hexagon as a function of the tile parameters, supported by computational evidence. The tilt angle of the growth form is also conjectured, based on the geometry of triangulation lines.

The proof strategy involves splitting and recombining tiles to obtain a tiling combinatorially equivalent to the hexagonal lattice, then transferring geodesic and growth form properties via duality.

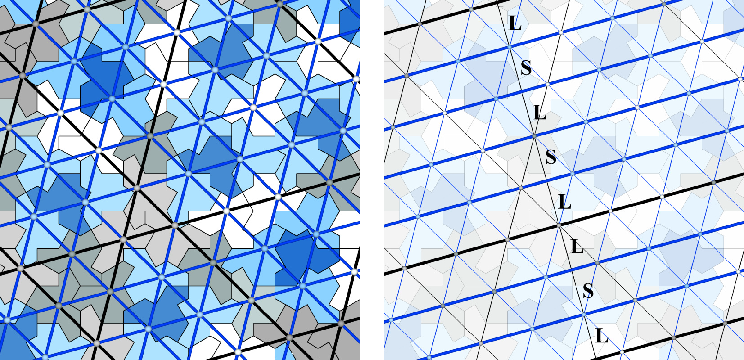

Figure 15: Left to right: Split flipped hats into three parts – Join parts to adjacent light blue hats – Hexagon mesh connectivity – Dual triangle mesh.

Figure 16: Geodetic chains on the triangle tiling.

Figure 17: Black and blue triangulation lines in the hat tiling -- labelled gaps between lines.

Figure 18: Top row: a cluster in HAT; bottom row: corresponding cluster in HAT1.

Tilings Without Growth Forms

Not all tilings admit a growth form. The paper provides a constructive example: a tiling by 1×1 and 2×2 squares arranged in strips of exponentially increasing width. In this case, the scaled coordination shells do not converge, demonstrating that the existence of a growth form is not guaranteed, even for simple combinatorial rules.

Figure 19: A tiling with no growth form.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The results establish a rigorous foundation for the computation and classification of growth forms in periodic and regular grid tilings, with explicit algorithms and formulas. For substitution and aperiodic tilings, the landscape is more fragmented, with only isolated cases resolved and several open questions remaining:

- Existence and Computability: There is no universal criterion or algorithm for determining the existence or explicit form of growth forms in substitution tilings.

- Dependence on Corona Definition: The choice of neighborhood (corona) definition can affect the growth form, especially in nonperiodic cases, and current proofs do not generalize.

- Fractal and Nonconvex Growth Forms: While conjectured to be impossible, the existence of fractal or nonconvex growth forms is not ruled out.

- Algorithmic Complexity: For periodic and grid tilings, the computation is tractable; for substitution tilings, it is generally intractable without further structural insight.

From a practical perspective, growth forms provide a tool for analyzing the large-scale geometry of tilings, with applications in crystallography, materials science, and the paper of quasicrystals. The connection to coordination sequences and topological densities links the combinatorial structure of tilings to physical properties of materials.

Conclusion

This work synthesizes the current understanding of growth forms in tiling theory, providing explicit results for periodic and grid tilings, and highlighting the complexity and open problems in substitution and aperiodic cases. The existence of non-polytopal or even nonconvex growth forms remains an intriguing possibility, and the development of general criteria or algorithms for substitution tilings is a significant open problem. The interplay between combinatorial, geometric, and physical aspects of tilings ensures that growth forms will remain a central object of paper in both mathematics and the physical sciences.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Open Problems

- Decide existence of growth form for substitution tilings

- Compute growth form for substitution tilings when it exists

- Nonpolygonal growth form of the L‑tetromino substitution tiling

- Geometry of hexagonal growth forms in hat and Tile(1,b) tilings

- Area formula for growth forms of Tile(1,b) tilings

- Tilt angle of the hat tiling’s growth hexagon

- Fractal nature of growth forms

- Convexity conditions for growth forms in nonregular grid tilings

Continue Learning

- How does the paper establish the algorithm for computing growth forms in periodic tilings?

- What role do grid tilings and dualization methods play in deriving explicit formulas for growth forms?

- In what ways do the computational experiments for substitution tilings challenge conventional growth form expectations?

- How might the findings on growth forms influence practical applications in crystallography and materials science?

- Find recent papers about aperiodic tilings.

Related Papers

- An aperiodic monotile (2023)

- Polygonal corona limit on multigrid dual tilings (2024)

- Geometrical Penrose Tilings are characterized by their 1-atlas (2022)

- Structural aspects of tilings (2008)

- An aperiodic tiling of variable geometry made of two tiles, a triangle and a rhombus of any angle (2021)

- Families of convex tilings (2021)

- The multinomial tiling model (2021)

- An aperiodic monotile that forces nonperiodicity through dendrites (2019)

- Corona limits of tilings : Periodic case (2017)

- Symmetries of Monocoronal Tilings (2014)

Authors (2)

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.

Tweets

This paper has been mentioned in 2 tweets and received 13 likes.

Upgrade to Pro to view all of the tweets about this paper:

alphaXiv

- Growth Forms of Tilings (6 likes, 0 questions)