- The paper demonstrates that discrete fully-connected networks capture simplicity bias by correlating DNF complexity with effective Boolean function generalisation.

- It employs methods like Metropolis-Hastings and SGD to illustrate how weight decay intensifies the network’s preference for simpler functions.

- The study highlights challenges in learning complex Boolean functions and suggests extending the framework to continuous inputs for broader applicability.

Characterising the Inductive Biases of Neural Networks on Boolean Data

The paper "Characterising the Inductive Biases of Neural Networks on Boolean Data" (2505.24060) explores how deep neural networks manage to generalise across tasks despite overparameterisation. The authors propose a discrete fully-connected network (DFCN) model that reveals the relationship between a network's inductive prior, its training dynamics, and eventual generalisation. This paper advances the understanding of generalisation by detailing how each component—inductive bias, training dynamics, and feature learning—collectively drive generalisation. The analysis revolves around correlating Boolean functions' DNF representations with DFCN architectures.

Boolean Functions and Network Representation

The core idea is elucidating how neural networks represent Boolean functions using Disjunctive Normal Form (DNF) clauses, and adversities when training these networks are explained using a one-to-one correspondence between DNFs and DFCNs (Figure 1). DFCNs, structured with clauses as neurons, reflect Boolean functions in a simplified form. With inputs as vertices of an n-dimensional hypercube, functions map these vertices to binary outputs. The complexity measure $\Kdnf$ quantifies the lengths of the minimal DNF necessary to express a given Boolean function.

Figure 1: Representation of Boolean functions and their translation into DNF clauses.

Exploring Inductive Bias and Training Dynamics

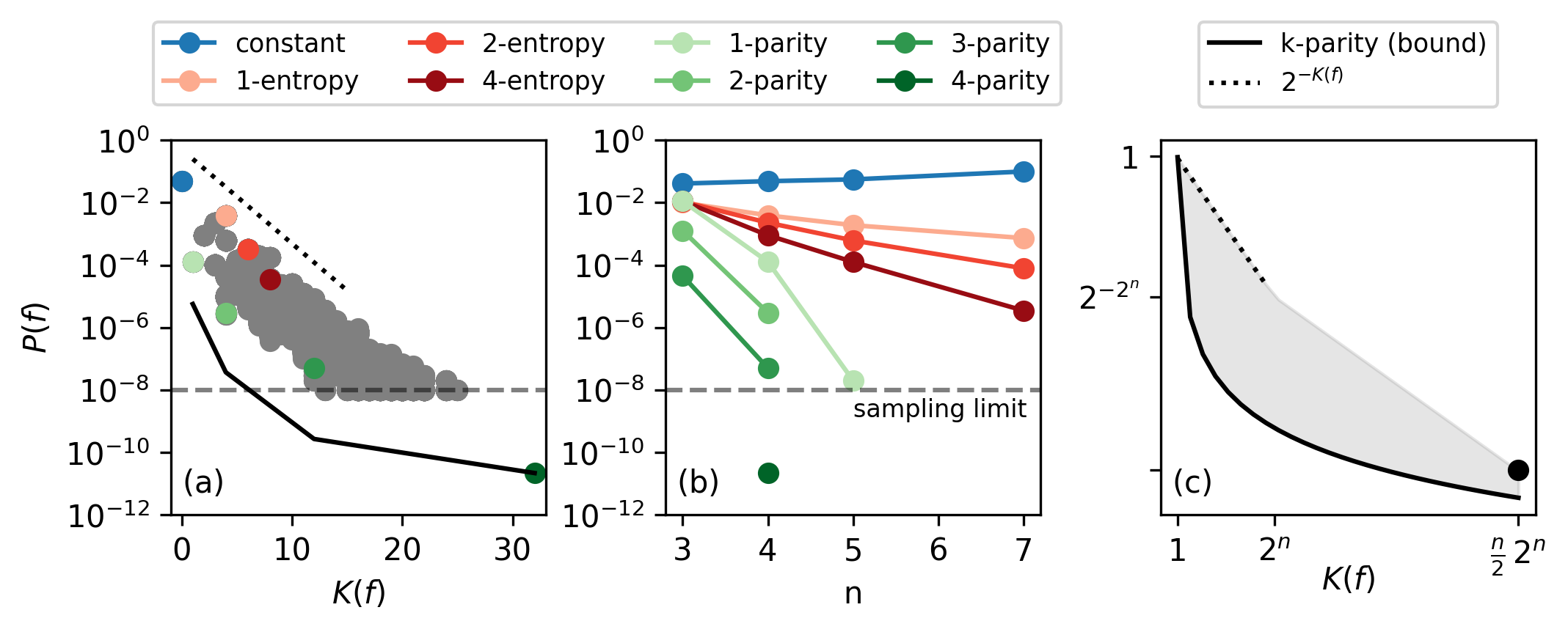

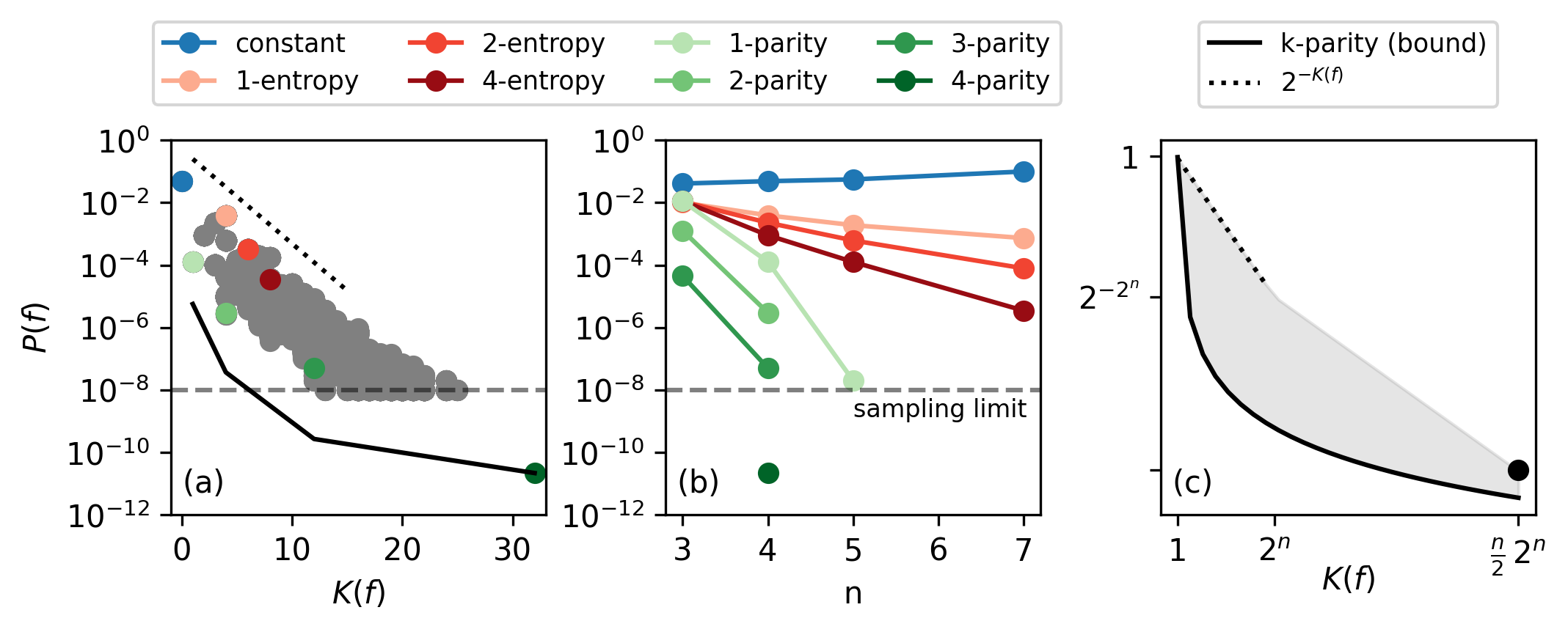

Neural network inductive bias is explored through sampling randomly initialised parameters and observing represented Boolean functions. Empirical evidence highlights a pronounced bias towards simpler functions—those with lower $\Kdnf$, indicating that network architecture predisposes learning towards less complex functions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prior probability P(f) correlated with DNF complexity $\Kdnf$ for networks with n=4.

The complexity measures impact training dynamics significantly. For instance, the networks favour learning functions with smaller DNF complexity due to their larger presence in parameter space. Simplicity bias as a Bayesian prior becomes evident when training dynamics amplify simplicity during weight decay, leveraging implicit bias to prefer minimal norm solutions.

Training Algorithms for Neural Networks

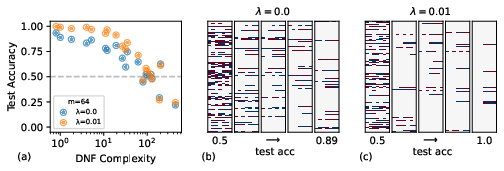

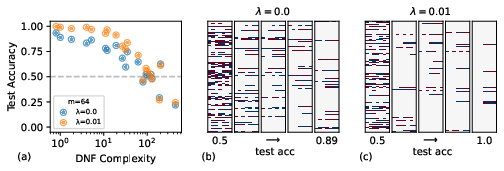

The authors employ algorithms like Metropolis-Hastings and SGD-like methods in different capacity explorations. The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm implements MCMC sampling, providing a posterior with explicit weight decay terms influencing function learning based on complexity. Results show weight decay enhances generalisation, amplifying simplicity bias and resulting in optimal feature learning for specific target functions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Inductive biases of trained DFCNs (n=7) with Bayesian sampling showcasing enhanced simplicity bias through weight decay.

Generalisation and Sparsity Constraints

Through a detailed analysis, the paper indicates functions with low $\Kdnf$ exhibit better generalisation due to stronger bias and enhanced feature learning. Furthermore, functions exceeding network capacity or possessing high complexity inherently defy typical learning paradigms, as the bias struggles to overcome complexity—and this is seen when training fails on complex parity functions despite increased data quantities (Figure 4).

*Figure 4: Training results for parity functions showing diminishing accuracy with increased data, highlighting inductive bias limitations._

*Figure 4: Training results for parity functions showing diminishing accuracy with increased data, highlighting inductive bias limitations._

Conclusions and Future Work

The paper concludes that understanding generalisation requires an intricate grasp of the simplicity biases induced by network architectures. Going forward, scaling the presented framework to continuous inputs and deeper models would present insightful comparisons between Boolean and continuous training regimes. Improved bounds on P(f) could refine theoretical predictions. Furthermore, new optimizer designs based on these biases could better suit architectural trends, potentially easing towards addressing complex problem domains.

The study provides an analytical viewpoint on the preconditioning that neural networks possess towards simplicity, urging a thoughtful contemplation of network design biases when modelling data and structuring learning tasks in AI research.

*Figure 4: Training results for parity functions showing diminishing accuracy with increased data, highlighting inductive bias limitations._

*Figure 4: Training results for parity functions showing diminishing accuracy with increased data, highlighting inductive bias limitations._