- The paper introduces a novel, controlled LEGO benchmark to assess visual perspective taking, revealing critical spatial reasoning weaknesses in VLMs.

- The paper reveals that while VLMs excel at object recognition and scene understanding, they struggle with intrinsic, agent-based spatial reasoning.

- The study shows that directional biases and prompt sensitivities highlight the need for explicit geometric modeling to enhance VLMs' perspective-taking capabilities.

Evaluating Visual Perspective Taking in Vision-LLMs

Introduction

The paper "Beyond Recognition: Evaluating Visual Perspective Taking in Vision LLMs" (2505.03821) presents a systematic investigation into the capacity of state-of-the-art Vision-LLMs (VLMs) to perform visual perspective taking (VPT). While VLMs have demonstrated strong performance in object recognition and scene understanding, their ability to reason about spatial relationships and to adopt the visual perspective of agents within a scene remains underexplored. This work introduces a novel, controlled benchmark inspired by human VPT tests, and provides a detailed analysis of VLMs' performance across a hierarchy of visual cognitive tasks.

Experimental Design

The authors constructed a dataset of 144 visual tasks, each depicting a single humanoid minifigure and a single object, with systematic variation in object placement, minifigure orientation, and camera viewpoint. The use of LEGO elements ensures precise control over scene geometry and eliminates confounds from pretraining data contamination. Each visual task is paired with seven open-ended diagnostic questions, targeting three cognitive categories: scene understanding, spatial reasoning, and visual perspective taking.

Figure 1: Sixteen representative tasks illustrating the systematic variation in object placement, minifigure orientation, and camera angle.

The diagnostic questions are designed to probe:

- Scene Understanding: Object recognition, counting, and placement (e.g., "How many non-minifigure objects are present?").

- Spatial Reasoning: Localization of objects and agent orientation in cardinal directions.

- Visual Perspective Taking: Determining what the minifigure can see and the egocentric location of objects from the minifigure's viewpoint.

All questions are answered in a zero-shot, open-ended format, with context cleared between queries and temperature set to zero to minimize stochasticity. Gold-standard answers are established via human annotation with high inter-rater agreement.

Model Evaluation and Metrics

The benchmark evaluates five prominent VLMs: GPT-4-Turbo, GPT-4o, Llama-3.2-11B-Vision-Instruct, Claude 3 Sonnet, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Performance is measured using a precision-based metric that accommodates both single and compound answers, capturing partial correctness where appropriate.

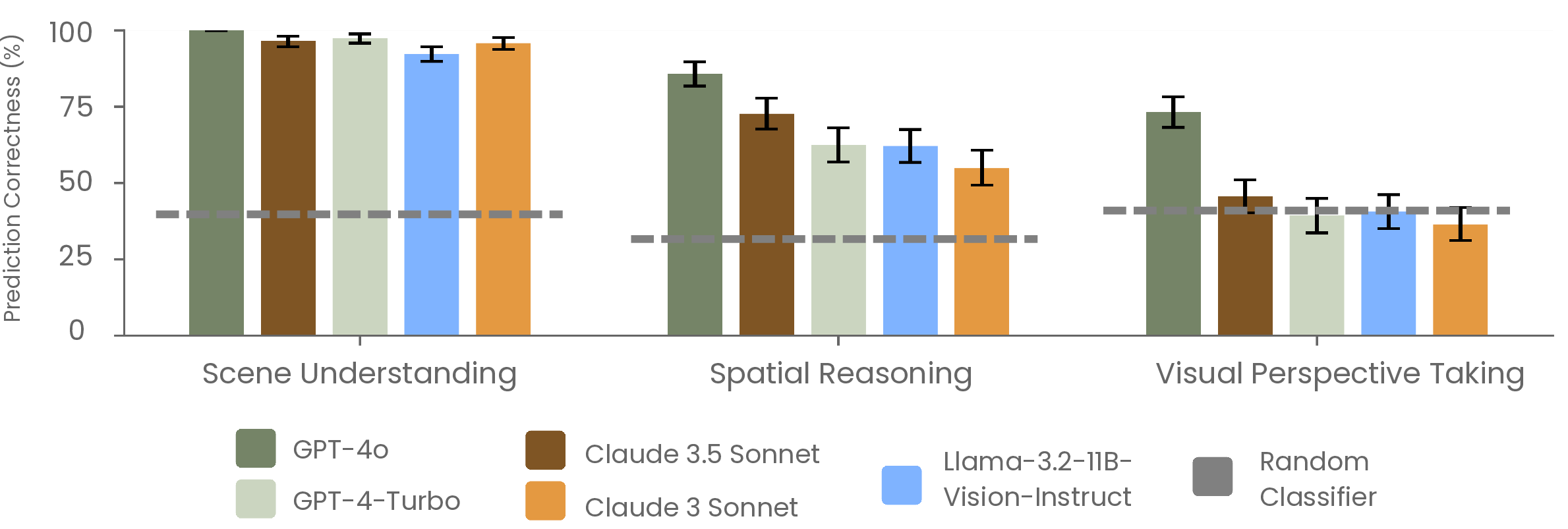

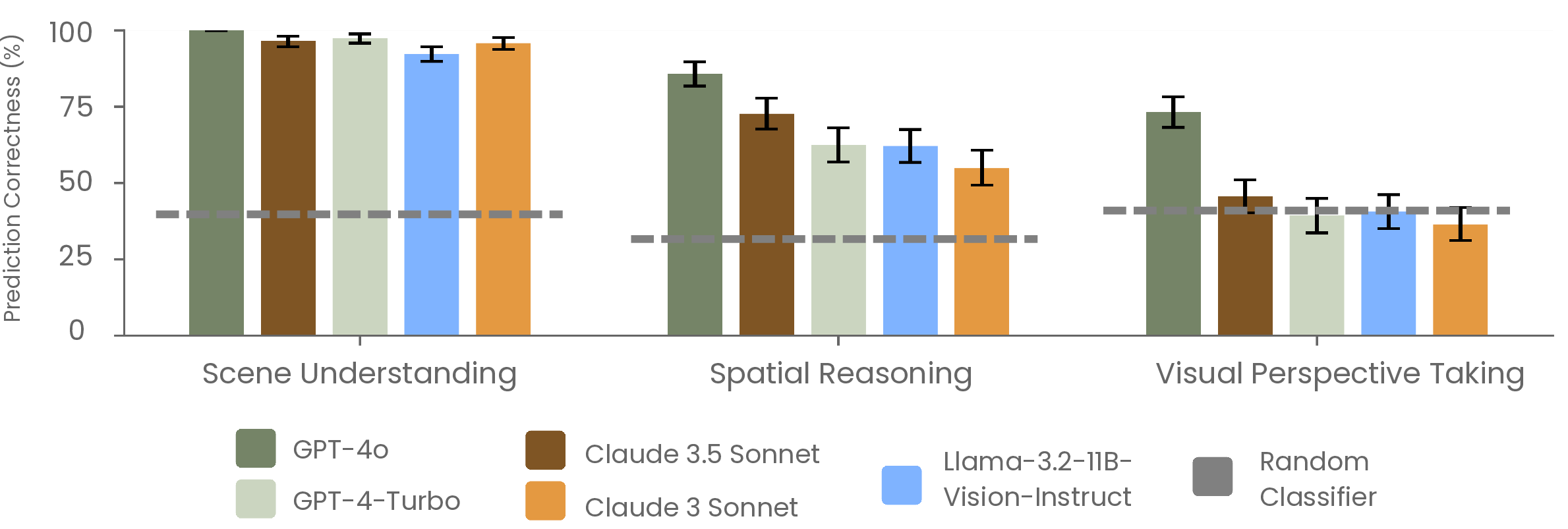

Figure 2: Prediction correctness across scene understanding, spatial reasoning, and visual perspective taking. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. The random classifier baseline reflects uninformed guessing.

Results

Scene Understanding

All models achieve near-ceiling performance on scene understanding tasks, with GPT-4o attaining 100% correctness and other models exceeding 92%. This confirms that object recognition and basic scene parsing are well within the capabilities of current VLMs.

Spatial Reasoning

Performance degrades on spatial reasoning tasks, particularly when models must infer the orientation of the minifigure (Q5). While localization of objects relative to the minifigure (Q4) remains strong (e.g., GPT-4o at 98.6%), correctness on orientation drops sharply (e.g., GPT-4-Turbo at 41.7%). The discrepancy is attributed to the distinction between extrinsic (scene-based) and intrinsic (agent-based) reference frames. Notably, several models exhibit strong directional biases, such as a persistent preference for "east" regardless of visual evidence, which persists even when contextual cues are manipulated or explicit cardinal markers are overlaid on the image.

Visual Perspective Taking

The most significant performance collapse occurs in visual perspective taking. For Q6 (can the minifigure see the object?), only GPT-4o achieves high accuracy (87.5%), while others fall below 56%. For Q7 (where is the object from the minifigure's perspective?), all models perform poorly, with correctness ranging from 30% to 59%. Models frequently misclassify objects behind the minifigure as being to its left or right, indicating a failure to simulate egocentric spatial relations.

Further analysis reveals that providing the ground-truth orientation as a prompt hint yields only marginal improvements in perspective-taking tasks, suggesting that the deficit is not solely due to failures in orientation estimation but reflects a deeper inability to perform geometric transformations required for VPT.

Error Analysis and Biases

The paper conducts extensive ablation experiments to probe the sources of model errors and biases:

- Directional Bias: Persistent "east" bias in orientation persists across manipulations of object presence, zoom level, explicit cardinal overlays, and even when replacing minifigures with real human figures.

- Prompt Sensitivity: The order of cardinal directions in the prompt influences model predictions, but does not eliminate the underlying bias.

- Premise Rejection: Some models (notably Claude 3 Sonnet) systematically reject the premise of VPT questions, e.g., by asserting that a LEGO minifigure cannot "see," indicating limitations in pragmatic reasoning or overfitting to literal interpretations.

Implications and Theoretical Considerations

The results demonstrate a clear gap between VLMs' proficiency in object-centric recognition and their capacity for spatial and perspective-dependent reasoning. The inability to reliably infer another agent's visual perspective constrains the deployment of VLMs in domains requiring collaborative, embodied, or safety-critical reasoning, such as robotics, autonomous vehicles, and human-robot interaction.

The findings suggest that current VLM architectures, which excel at pattern recognition and language-image alignment, lack mechanisms for explicit geometric modeling or embodied simulation. The observed biases and error patterns indicate reliance on linguistic priors and memorized defaults rather than genuine spatial reasoning. This aligns with recent critiques of VLMs' compositionality and generalization in spatial tasks (Buschoff et al., 2023, Cheng et al., 3 Jun 2024, Linsley et al., 6 Jun 2024).

Future Directions

To address these limitations, the paper advocates for the integration of explicit geometric representations and spatial reasoning modules within VLM architectures. Potential directions include:

- Incorporation of 3D scene understanding and mental rotation capabilities to support egocentric transformations.

- Training protocols that emphasize embodied perspective-taking and spatial tasks, potentially leveraging synthetic data with controlled agent viewpoints.

- Hybrid models that combine neural perception with symbolic or geometric reasoning engines for robust spatial inference.

Such advances are critical for enabling VLMs to move beyond static scene inventories toward dynamic, agent-centric understanding required for real-world interaction and collaboration.

Conclusion

This work provides a rigorous, controlled evaluation of visual perspective taking in VLMs, revealing that despite strong object recognition, current models exhibit substantial deficits in spatial reasoning and egocentric perspective-taking. The results highlight the need for architectural and training innovations to endow VLMs with the geometric and embodied reasoning capabilities necessary for advanced visual cognition and safe, effective deployment in interactive environments.