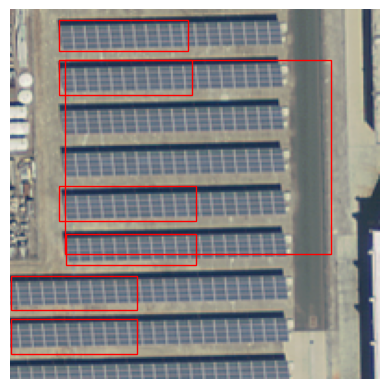

Exploring Different Levels of Supervision for Detecting and Localizing Solar Panels on Remote Sensing Imagery

Abstract: This study investigates object presence detection and localization in remote sensing imagery, focusing on solar panel recognition. We explore different levels of supervision, evaluating three models: a fully supervised object detector, a weakly supervised image classifier with CAM-based localization, and a minimally supervised anomaly detector. The classifier excels in binary presence detection (0.79 F1-score), while the object detector (0.72) offers precise localization. The anomaly detector requires more data for viable performance. Fusion of model results shows potential accuracy gains. CAM impacts localization modestly, with GradCAM, GradCAM++, and HiResCAM yielding superior results. Notably, the classifier remains robust with less data, in contrast to the object detector.

- IEA, “Electricity market report – update 2023,” https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-market-report-update-2023, License: CC BY 4.0, Tech. Rep.

- ——, “Installation of about 600 million heat pumps covering 20buildings heating needs required by 2030,” https://www.iea.org/reports/installation-of-about-600-million-heat-pumps-covering-20-of-buildings-heating-needs-required-by-2030, License: CC BY 4.0, Tech. Rep.

- S. Dawn, V. Saxena, and B. Sharma, “Remote sensing image registration techniques: A survey,” in Proc. Image and Signal Processing (ICISP 2010). Canada: Springer.

- C. Sager, C. Janiesch, and P. Zschech, “A survey of image labelling for computer vision applications,” Journal of Business Analytics, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 91–110, 2021.

- T.-Y. Lin, M. Maire, S. Belongie, J. Hays, P. Perona, D. Ramanan, P. Dollár, and C. L. Zitnick, “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context,” in Proc. ECCV, 2014.

- J. Deng, W. Dong, R. Socher, L.-J. Li, K. Li, and L. Fei-Fei, “ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database,” in Proc. IEEE CVPR, 2009.

- C. Fasana, S. Pasini, F. Milani, and P. Fraternali, “Weakly supervised object detection for remote sensing images: A survey,” Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 21, p. 5362, 2022.

- R. R. Selvaraju, M. Cogswell, A. Das, R. Vedantam, D. Parikh, and D. Batra, “Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-based Localization,” in Proc. IEEE ICCV, 2017.

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks,” NIPS, vol. 25, pp. 1097–1105, 2012.

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition,” in Proc. IEEE CVPR, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Z. Zou, K. Chen, Z. Shi, Y. Guo, and J. Ye, “Object detection in 20 years: A survey,” Proceedings of the IEEE, 2023.

- R. Girshick, J. Donahue, T. Darrell, and J. Malik, “Region-based convolutional networks for accurate object detection and segmentation,” IEEE PAMI, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 142–158, 2015.

- S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun, “Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks,” in NIPS, vol. 28, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2015/file/14bfa6bb14875e45bba028a21ed38046-Paper.pdf

- J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick, and A. Farhadi, “You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection,” in Proc. IEEE CVPR, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- J. Bastings and K. Filippova, “The elephant in the interpretability room: Why use attention as explanation when we have saliency methods?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.05607, 2020.

- C. Rudin, “Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead,” Nature machine intelligence, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 206–215, 2019.

- A. Chattopadhay, A. Sarkar, P. Howlader, and V. N. Balasubramanian, “Grad-CAM++: Generalized Gradient-Based Visual Explanations for Deep Convolutional Networks,” in IEEE WACV. IEEE, 2018, pp. 839–847.

- R. L. Draelos and L. Carin, “Use hirescam instead of grad-cam for faithful explanations of convolutional neural networks,” arXiv e-prints, pp. arXiv–2011, 2020.

- S. Srinivas and F. Fleuret, “Full-gradient representation for neural network visualization,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 32, 2019.

- M. B. Muhammad and M. Yeasin, “Eigen-cam: Class activation map using principal components,” in Intl. Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2020.

- J. Gildenblat and contributors, “Pytorch library for cam methods,” https://github.com/jacobgil/pytorch-grad-cam, 2021.

- F. Zhang, B. Du, L. Zhang, and M. Xu, “Weakly supervised learning based on coupled convolutional neural networks for aircraft detection,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 5553–5563, 2016.

- X. Qian, C. Li, W. Wang, X. Yao, and G. Cheng, “Semantic segmentation guided pseudo label mining and instance re-detection for weakly supervised object detection in remote sensing images,” Intl. Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 119, 2023.

- D. P. Kingma and M. Welling, “Auto-encoding variational bayes,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114, 2013.

- W. Chen, H. Xu, Z. Li, D. Pei, J. Chen, H. Qiao, Y. Feng, and Z. Wang, “Unsupervised anomaly detection for intricate kpis via adversarial training of vae,” in IEEE Conf. on Computer Communications (INFOCOM), 2019, pp. 1891–1899.

- J. Silva-Rodríguez, V. Naranjo, and J. Dolz, “Looking at the whole picture: constrained unsupervised anomaly segmentation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.00482, 2021.

- T. Schlegl, P. Seeböck, S. M. Waldstein, G. Langs, and U. Schmidt-Erfurth, “f-anogan: Fast unsupervised anomaly detection with generative adversarial networks,” Medical image analysis, vol. 54, pp. 30–44, 2019.

- “Pytorch faster r-cnn implementation.”

- D. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” International Conference on Learning Representations, 12 2014.

- “Pytorch resnet-50,” https://pytorch.org/vision/main/models/generated/torchvision.models.resnet50.

- K. Bradbury, R. Saboo, J. Malof, T. Johnson, A. Devarajan, W. Zhang, L. Collins, R. Newell, A. Streltsov, and W. Hu, “Distributed Solar Photovoltaic Array Location and Extent Data Set for Remote Sensing Object Identification,” 7 2020. [Online]. Available: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Distributed_Solar_Photovoltaic_Array_Location_and_Extent_Data_Set_for_Remote_Sensing_Object_Identification/3385780

- K. Bradbury, R. Saboo, T. L. Johnson, J. M. Malof, A. Devarajan, W. Zhang, L. M. Collins, and R. G. Newell, “Distributed solar photovoltaic array location and extent dataset for remote sensing object identification,” Scientific Data, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 160106, Dec 2016. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.106

- J. Yu, Z. Wang, A. Majumdar, and R. Rajagopal, “Deepsolar: A machine learning framework to efficiently construct a solar deployment database in the united states,” Joule, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 2605–2617, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542435118305701

- “Is AQ or F score the last word in determining individual effort,” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 513–525, 1943.

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, “U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.