Invariant Risk Minimization (1907.02893v3)

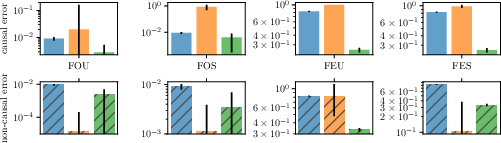

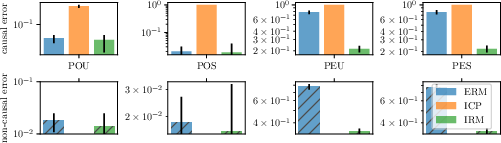

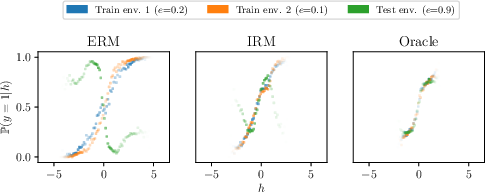

Abstract: We introduce Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM), a learning paradigm to estimate invariant correlations across multiple training distributions. To achieve this goal, IRM learns a data representation such that the optimal classifier, on top of that data representation, matches for all training distributions. Through theory and experiments, we show how the invariances learned by IRM relate to the causal structures governing the data and enable out-of-distribution generalization.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The paper introduces Invariant Risk Minimization (IRM) and provides initial theory and simulations. The following gaps and open questions remain unresolved and point to concrete directions for future research:

- How to construct or discover environments from raw datasets when explicit environment labels are unavailable, without inadvertently destroying the invariances of interest or introducing spurious correlations.

- Practical criteria and procedures for ensuring “diversity” of environments; e.g., data-driven tests or diagnostics to assess whether training environments satisfy a usable analog of “linear general position” in finite samples.

- Finite-sample generalization guarantees for IRM: sample complexity bounds, variance analyses, and concentration results for the empirical invariance penalty and risk terms.

- Nonlinear generalization theory: a precise “nonlinear general position” assumption or alternative conditions under which IRM with nonlinear representations provably transfers invariance from training to unseen environments.

- Formal characterization of when two (or few) environments suffice, beyond linear models—i.e., necessary and sufficient conditions relating environment diversity, hypothesis class, and the form of invariance.

- Robustness to imperfect or approximate invariance: quantify how small violations of invariance affect out-of-distribution (OOD) error, and derive stability bounds for IRM under model misspecification.

- Identification conditions for causal parents via IRM without a known causal graph, especially with high-dimensional perceptual inputs; clarify when IRM recovers causal predictors versus merely invariant but non-causal correlates.

- Extension of the invariance penalty to nonlinear classifiers

w(beyond linear last-layer), including design of differentiable penaltiesD(w, Φ, e)for richer hypothesis classes and analysis of their benefits and pitfalls. - Failure modes of IRMv1’s fixed scalar classifier

w = 1.0: enumerate non-invariant predictors that can yield near-zero penalties (e.g., trivial or saturated representations) and devise mechanisms to detect and prevent them. - Optimization challenges: the IRM objective is nonconvex with multiple connected components; investigate initialization strategies, regularization schemes, and optimization algorithms with convergence guarantees.

- Sensitivity to the trade-off hyperparameter

λ: systematic methods to tuneλwithout access to target/OOD environments (e.g., proxy criteria, bilevel selection, or PAC-Bayes-inspired controls). - Handling multi-class and multivariate outputs more naturally than scaling by a scalar

w = 1.0; design and analyze penalties tailored to softmax classifiers and structured outputs. - Requirements on support overlap: IRM’s invariance notion relies on equality of conditional expectations on the intersection of supports; develop techniques for partial or non-overlapping supports and quantify the impact on OOD generalization.

- Interaction with noise heteroskedasticity and interventions on

Y: broaden validity conditions beyond finite variance ranges and propose principled environment baselinesr_eintegrated with IRM (not only robust baselines). - Empirical scalability: large-scale, real-world evaluations beyond synthetic setups—benchmark breadth, ablations (e.g., number/diversity of environments, architecture, optimizer), and comparisons to strong modern OOD baselines.

- Guidance for environment design in practice (e.g., feature-based splits, time/space contexts, controlled interventions) to reliably expose spurious vs. stable correlations for IRM to exploit.

- Combining IRM with complementary strategies (e.g., causal data augmentation, counterfactual generation, domain adversarial methods) and understanding when such hybrids help or hurt invariance and OOD performance.

- Verifiable conditions for the “scrambled setup” (latent

Zmixed into observedXviaS): specify identifiable classes ofS(beyond partial invertibility onZ1) and derive algorithms that can learn such demixing robustly. - Extension of Proposition 1 (robust learning equivalence to weighted ERM) to non-differentiable losses or constrained models; clarify whether robust formulations outside KKT assumptions might capture invariance differently.

- Diagnostics to detect when IRM is counterproductive (e.g., no true invariances exist or environments are ill-posed), and adaptive strategies to revert to ERM or alternate OOD methods accordingly.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.