- The paper introduces UMAP, which leverages fuzzy simplicial sets to capture both local connectivity and global topological structure for dimension reduction.

- It employs a two-phase process, constructing a weighted k-nearest neighbor fuzzy graph and refining an initial spectral embedding via stochastic gradient descent.

- Empirical evaluations across diverse datasets show UMAP outperforms t-SNE and LargeVis in scalability, stability, and preservation of data topology.

Theoretical Foundations

UMAP is a manifold learning technique for dimension reduction, grounded in Riemannian geometry and algebraic topology. The algorithm is motivated by the need to construct embeddings that preserve both local and global topological structure, addressing limitations in prior methods such as t-SNE and Laplacian Eigenmaps. UMAP models the data as lying on a manifold and approximates local geodesic distances using a variable metric, ensuring uniformity of data distribution via local normalization. This is formalized by constructing a family of extended-pseudo-metric spaces, each centered at a data point, and then merging these via fuzzy simplicial sets—a categorical generalization of simplicial complexes.

The core innovation is the use of fuzzy simplicial sets to encode local connectivity and membership strengths, which are then unified into a global topological representation. The optimization objective is to minimize the cross-entropy between the fuzzy topological representations of the high-dimensional data and its low-dimensional embedding, focusing on the 1-skeleton (edges) for computational tractability.

Algorithmic Structure and Implementation

UMAP operates in two main phases: graph construction and graph layout. In the first phase, a weighted k-nearest neighbor graph is constructed using approximate nearest neighbor search (typically NN-Descent), with edge weights determined by a smoothed exponential kernel that incorporates local connectivity constraints. The symmetrization of the directed graph is performed via a probabilistic t-conorm, yielding an undirected fuzzy graph.

In the second phase, the algorithm initializes the embedding using spectral methods (eigenvectors of the normalized Laplacian), then refines the layout via stochastic gradient descent to minimize the fuzzy set cross-entropy. Attractive and repulsive forces are applied between points, with negative sampling used to efficiently approximate the repulsive term. The membership strength function in the embedded space is parameterized and fitted to a differentiable approximation for gradient-based optimization.

The algorithm is highly scalable, with empirical complexity O(N1.14) for nearest neighbor search and O(kN) for optimization, and supports arbitrary embedding dimensions and sparse input formats.

Hyperparameter Effects

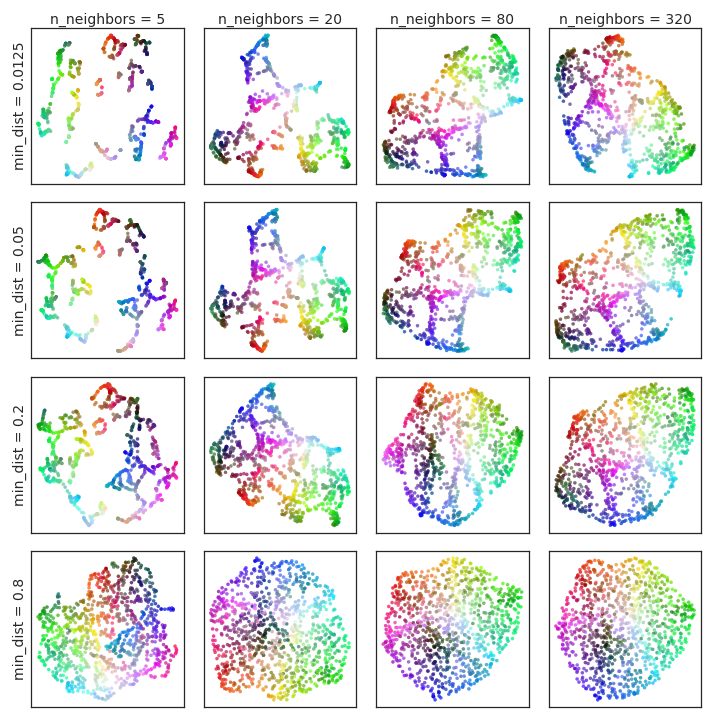

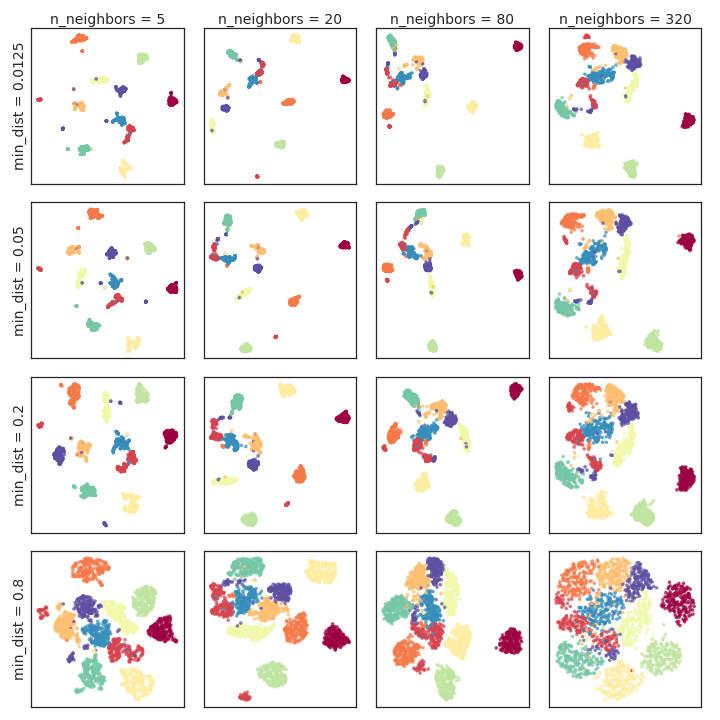

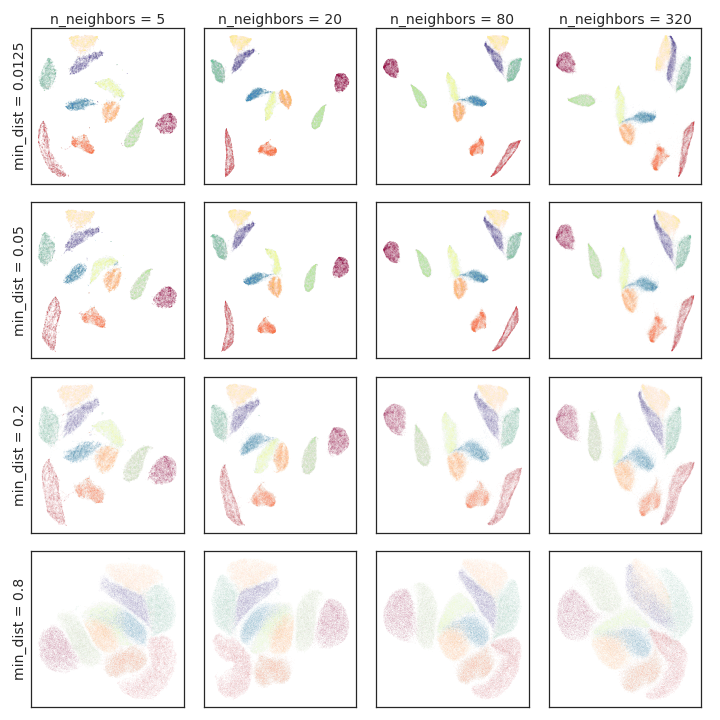

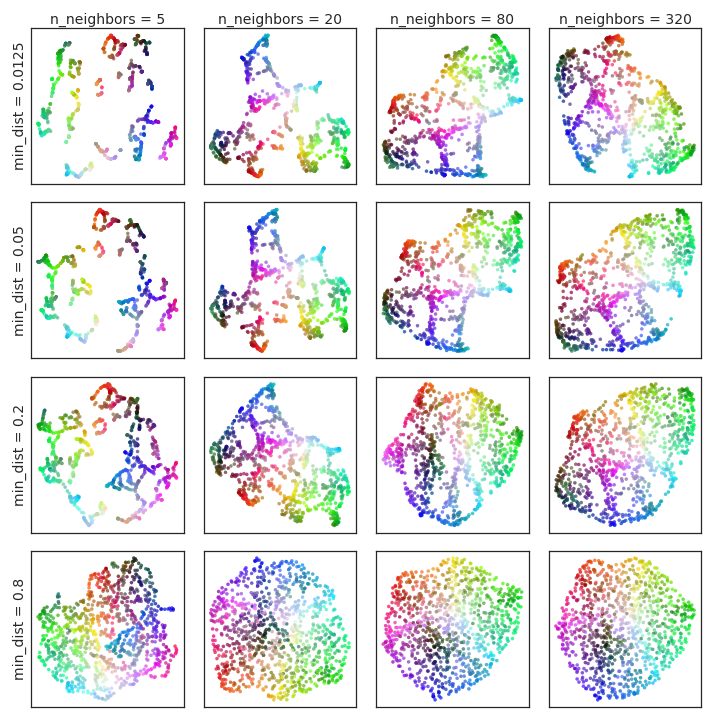

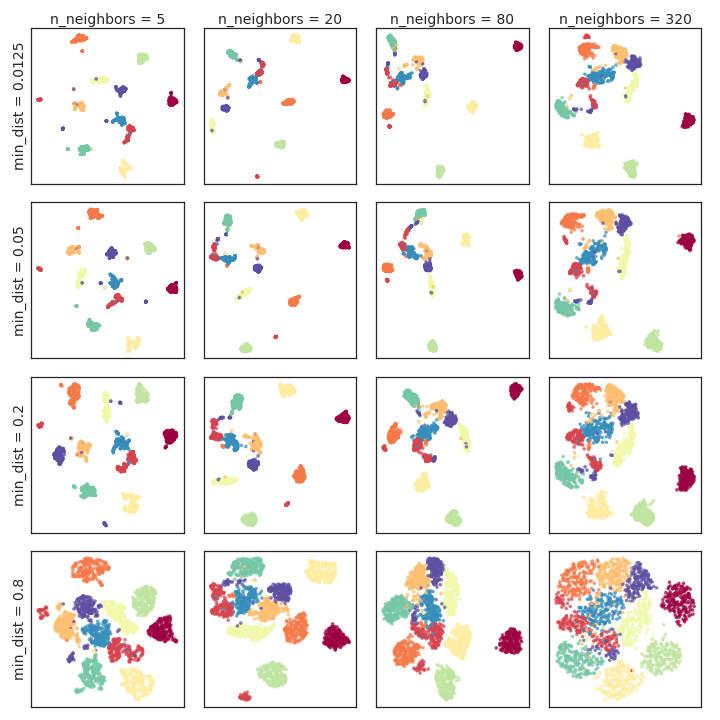

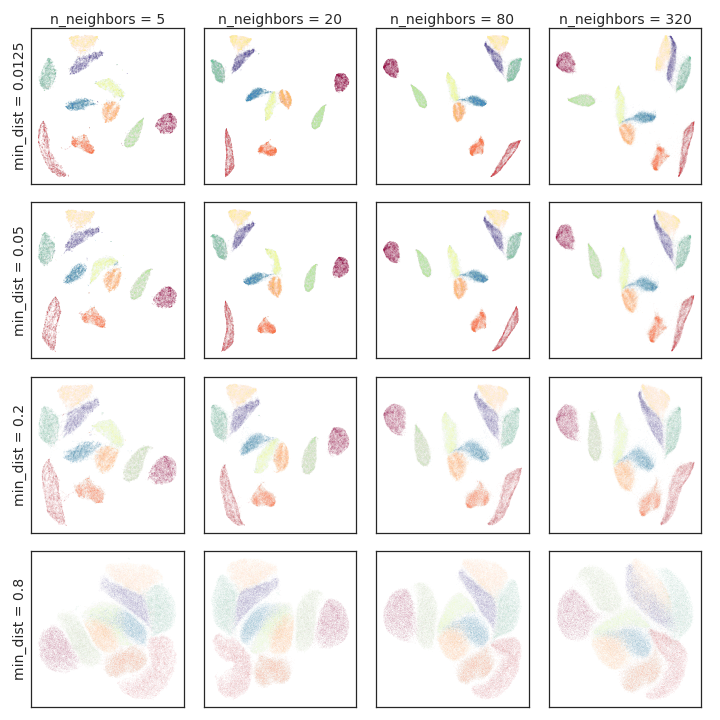

UMAP exposes several hyperparameters: the number of neighbors (n), target embedding dimension (d), minimum distance (min-dist), and number of optimization epochs. The number of neighbors controls the scale of local manifold approximation, trading off fine detail against global structure. The min-dist parameter governs the minimum allowed distance between points in the embedding, affecting cluster compactness and visualization aesthetics.

Figure 1: Variation of UMAP hyperparameters n and min-dist result in different embeddings for uniform random samples from a 3D color-cube; low n values can spuriously interpret noise as structure.

Figure 2: Hyperparameter variation for the PenDigits dataset, illustrating the impact on cluster separation and internal structure.

Figure 3: Hyperparameter variation for the MNIST dataset, showing effects on digit cluster compactness and separation.

Empirical Evaluation

UMAP is evaluated on diverse datasets (PenDigits, COIL-20/100, MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, Shuttle, scRNA-seq, Flow Cytometry, GoogleNews word vectors, and synthetic high-dimensional integer data). Qualitative comparisons demonstrate that UMAP preserves both local and global structure, often outperforming t-SNE and LargeVis in maintaining topological features such as loops and cluster relationships.

Figure 4: Comparison of UMAP, t-SNE, LargeVis, Laplacian Eigenmaps, and PCA on several datasets; UMAP preserves global and local structure effectively.

Quantitative evaluation using kNN classifier accuracy across embedding spaces shows that UMAP matches or exceeds t-SNE and LargeVis, especially for larger k values, indicating superior non-local structure preservation.

Figure 5: kNN classifier accuracy for COIL-20 and PenDigits embeddings; UMAP outperforms t-SNE and LargeVis for larger k.

Figure 6: kNN classifier accuracy for Shuttle, MNIST, and Fashion-MNIST; UMAP excels for large k, particularly on Shuttle.

Stability and Scalability

UMAP exhibits high stability under subsampling, as measured by normalized Procrustes distance, outperforming t-SNE and LargeVis in embedding consistency.

Figure 7: UMAP sub-sample embeddings remain close to the full embedding even for small subsamples, outperforming t-SNE and LargeVis.

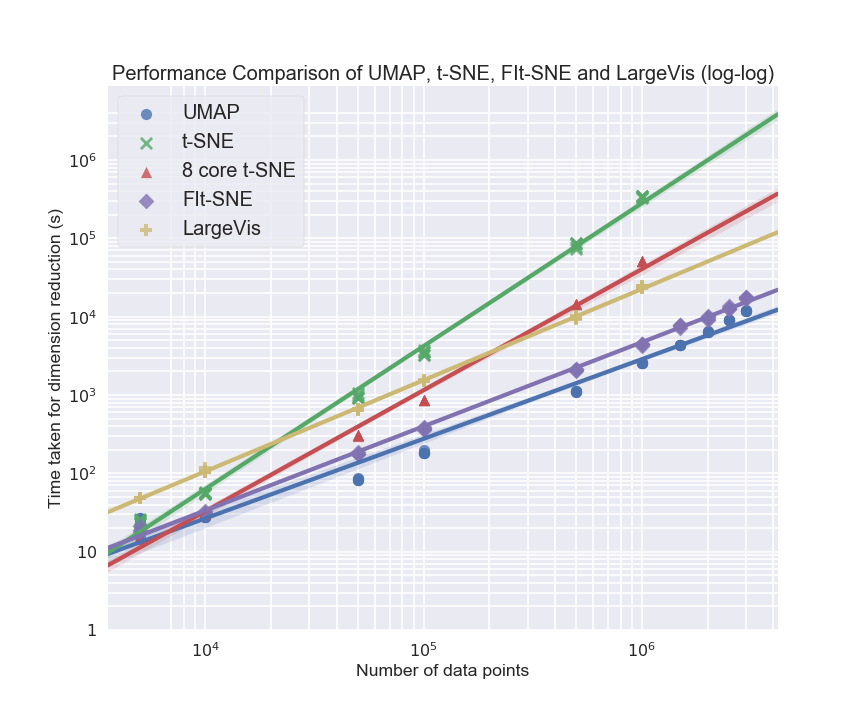

In terms of computational performance, UMAP scales linearly with embedding dimension and ambient dimension, in contrast to t-SNE's exponential scaling due to space tree structures.

Figure 8: UMAP and LargeVis scale linearly with embedding dimension, while t-SNE scales worse than exponentially.

Figure 9: UMAP maintains efficient runtime as ambient dimension increases, unlike t-SNE, FIt-SNE, and LargeVis.

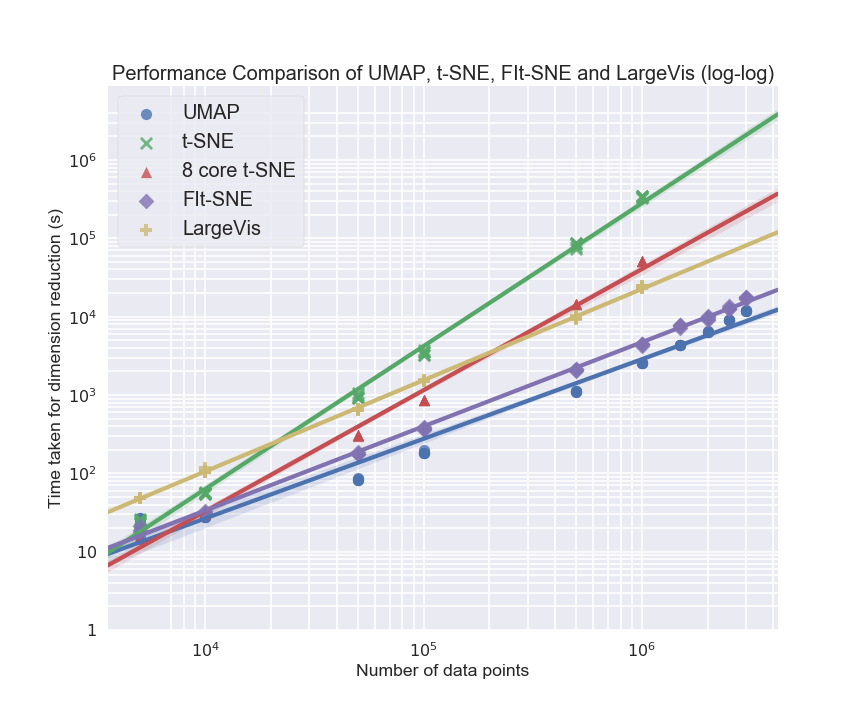

UMAP also demonstrates superior scaling with dataset size, enabling embedding of millions of points in high-dimensional spaces.

Figure 10: UMAP runtime scales favorably with dataset size compared to t-SNE (even multicore).

Figure 11: Visualization of 3 million GoogleNews word vectors embedded by UMAP.

Figure 12: Embedding of 30 million integers as binary vectors of prime divisibility, colored by density.

Figure 13: Embedding of 30 million integers, colored by integer value.

Limitations

UMAP, like other non-linear dimension reduction techniques, lacks interpretability of embedding dimensions and factor loadings. It may spuriously detect structure in noise for small or unstructured datasets, and is less suitable when global metric preservation is paramount. The algorithm's reliance on local structure can lead to suboptimal results for data with strong global features or highly non-uniform density. For small datasets, approximation errors from nearest neighbor search and negative sampling can degrade embedding quality.

Future Directions

Potential extensions include semi-supervised and supervised dimension reduction, heterogeneous data embedding, metric learning, and out-of-sample extension for new data points. Further research is needed on objective measures of global structure preservation and detection of spurious embeddings. Robustness improvements for small datasets and interpretability enhancements are also promising avenues.

Conclusion

UMAP provides a mathematically principled, scalable, and effective approach to dimension reduction, with strong empirical performance across a range of datasets and tasks. Its ability to preserve both local and global topological structure, combined with efficient computation, makes it suitable for visualization, clustering, and as a general-purpose preprocessing tool in machine learning pipelines. The theoretical framework based on fuzzy simplicial sets opens opportunities for further methodological advances in manifold learning and topological data analysis.