SIPHON: Towards Scalable High-Interaction Physical Honeypots

Abstract: In recent years, the emerging Internet-of-Things (IoT) has led to rising concerns about the security of networked embedded devices. In this work, we focus on the adaptation of Honeypots for improving the security of IoTs. Low-interaction honeypots are used so far in the context of IoT. Such honeypots are limited and easily detectable, and thus, there is a need to find ways how to develop high-interaction, reliable, IoT honeypots that will attract skilled attackers. In this work, we propose the SIPHON architecture - a Scalable high-Interaction Honeypot platform for IoT devices. Our architecture leverages IoT devices that are physically at one location and are connected to the Internet through so-called wormholes distributed around the world. The resulting architecture allows exposing few physical devices over a large number of geographically distributed IP addresses. We demonstrate the proposed architecture in a large scale experiment with 39 wormhole instances in 16 cities in 9 countries. Based on this setup, six physical IP cameras, one NVR and one IP printer are presented as 85 real IoT devices on the Internet, attracting a daily traffic of 700MB for a period of two months. A preliminary analysis of the collected traffic indicates that devices in some cities attracted significantly more traffic than others (ranging from 600 000 incoming TCP connections for the most popular destination to less than 50000 for the least popular). We recorded over 400 brute-force login attempts to the web-interface of our devices using a total of 1826 distinct credentials, from which 11 attempts were successful. Moreover, we noted login attempts to Telnet and SSH ports some of which used credentials found in the recently disclosed Mirai malware.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about making the internet safer by studying how hackers try to break into “smart” gadgets—like internet-connected cameras and printers. The researchers built a special trap (called a honeypot) that looks like many real devices spread around the world, even though they only had a handful of actual devices in one lab. Their system is called SIPHON, which stands for Scalable High-Interaction Physical Honeypots for IoT devices.

Key Objectives and Questions

The paper set out to answer simple, practical questions:

- How can we build a realistic, large-scale trap for smart devices that skilled hackers will actually try to attack?

- Can we do this using only a small number of real devices, while making them appear in many cities worldwide?

- What kinds of attacks do these devices attract, and where do those attacks come from?

- Do attackers behave differently depending on where they think the device is located?

- Does being listed on Shodan (a search engine for internet-connected devices) change how much a device gets attacked?

How They Did It (Methods)

Think of a honeypot like a fake storefront designed to catch shoplifters—but in this case, it’s a real gadget (like a camera) that hackers can interact with. The trick is making lots of people find it and try to mess with it, all while the researchers watch safely.

Here’s the approach, explained with everyday ideas:

- Real devices, many “front doors”: The team used a small number of actual IoT devices in their lab (around seven). Then they created many “wormholes”—these are like internet tunnels or forwarding lines with public IP addresses in different cities (for example, Frankfurt, London, Singapore). When someone tries to connect to the device in Frankfurt, the wormhole forwards that traffic back to the real device in the lab.

- High-interaction: Because the devices are real, attackers can do real things (like logging in, moving a camera, viewing video), which keeps skilled hackers interested and gives researchers better data than simple fakes.

- Scaling up: By combining a few real devices with many wormholes (public IPs from cloud providers like Amazon EC2, DigitalOcean, Linode), they made those few devices appear as 85 separate devices across 39 wormholes, in 16 cities, 9 countries.

- Forwarding and safety: Traffic was forwarded using secure tunnels (like SSH), and the devices were isolated inside the lab network for safety. All the incoming and outgoing data was captured for analysis.

- Shodan listing: Shodan is like Google for smart devices. The team watched how often their devices got attacked before and after the devices showed up on Shodan.

Main Findings and Why They Matter

The researchers found several important things. Here are the highlights:

- Big interest after Shodan listing: Once a device was listed on Shodan, the number of attack attempts quickly went up, especially in the first week. This suggests attackers use Shodan to find targets fast.

- Location matters: Devices “placed” (via wormholes) in some cities were attacked much more. Frankfurt got about 600,000 incoming TCP connections, while San Jose got around 50,000. This means attackers care about where they think a device is located.

- Most attacks targeted SSH: About 97% of the incoming connections aimed at port 22 (SSH), which is commonly used for remote logins. Even if the camera’s web page was the main target for viewing video, attackers still heavily probed SSH—often with passwords linked to known malware like Mirai.

- Brute-force logins: The team recorded over 400 brute-force login attempts (trying many passwords quickly) using 1,826 different usernames/passwords. Eleven attempts succeeded—and every successful login was on devices with easy or default passwords. Hard passwords worked: none were cracked.

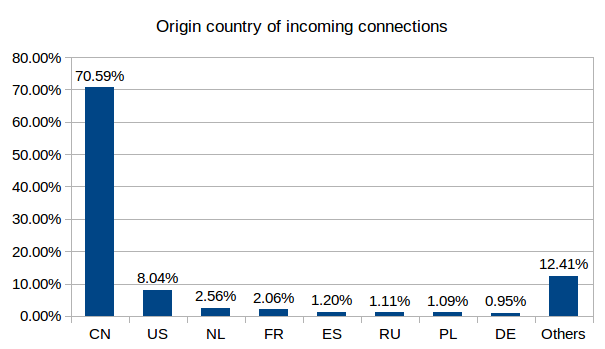

- Who and how: Over 70% of connections came from IP addresses located in China (note: attackers can route through any country, so this isn’t definitive). Many requests used common tools and browsers (Mozilla, Chrome) and scanning tools like Masscan. They also saw thousands of “Shellshock” attempts—an old trick to hijack systems.

- Cameras are popular: One specific D-Link camera model received the most attention, likely because its flaws had been publicly reported.

Overall traffic was heavy: roughly 700 MB per day, totaling about 20 GB across two months.

Implications and Impact

This work shows a practical, affordable way to study real attacks on smart devices:

- Better research, lower cost: By using a few real devices and many wormholes, researchers can observe genuine hacker behavior at scale without buying dozens of gadgets.

- Realistic interactions attract skilled attackers: High-interaction honeypots (where cameras move and show live video) draw in serious attackers, revealing more about new or advanced techniques.

- Shodan is a major driver: If a device is visible on Shodan, it’s quickly targeted. Device makers and owners should assume anything exposed to the internet will be found.

- Strong passwords matter: Default or simple passwords get broken; strong, unique passwords held up.

- Defenders can prioritize: Since some locations are attacked more, companies can focus extra monitoring where it counts. Security teams can also watch for heavy probing on common ports like SSH.

In short, SIPHON helps the security community learn how attackers operate against real IoT devices, so we can design better defenses and encourage safer device settings (like changing default passwords and limiting public exposure).

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.