Schrödinger's Navigator: Imagining an Ensemble of Futures for Zero-Shot Object Navigation

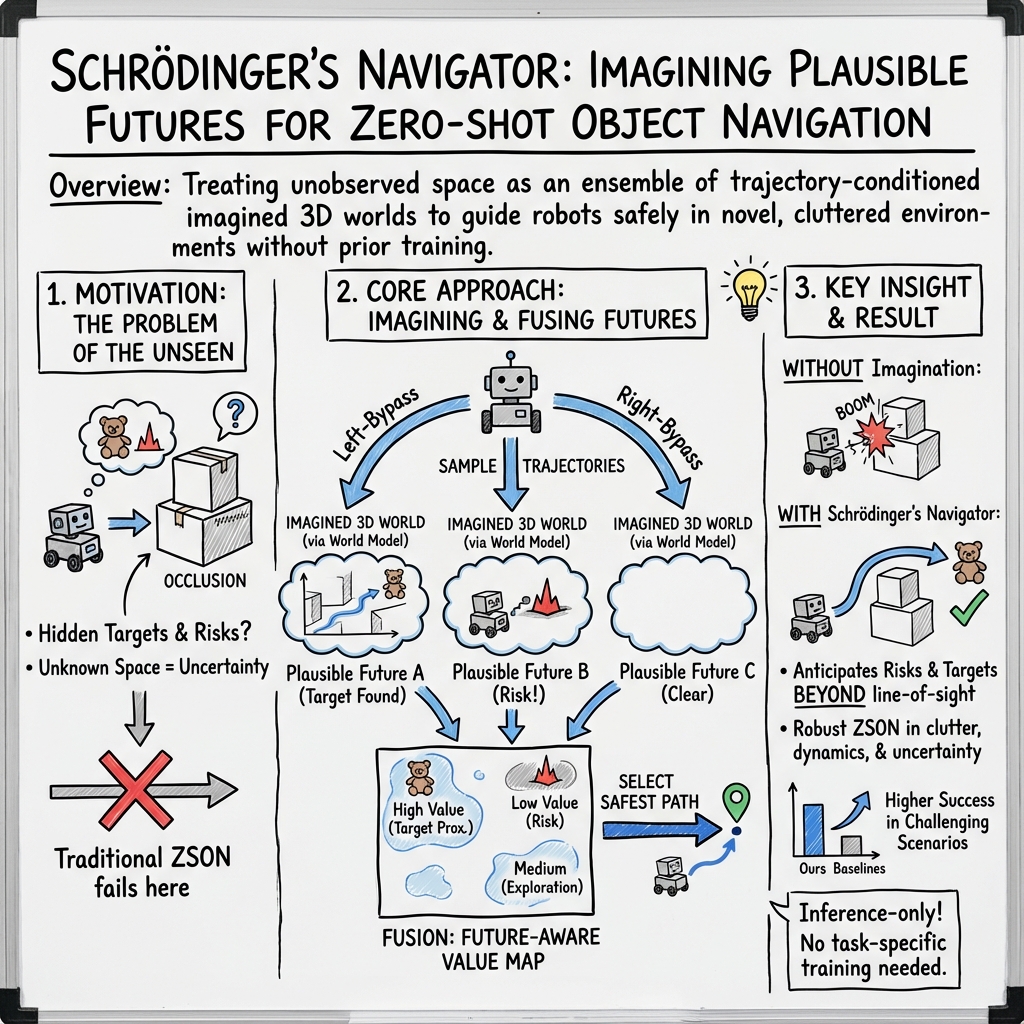

Abstract: Zero-shot object navigation (ZSON) requires a robot to locate a target object in a previously unseen environment without relying on pre-built maps or task-specific training. However, existing ZSON methods often struggle in realistic and cluttered environments, particularly when the scene contains heavy occlusions, unknown risks, or dynamically moving target objects. To address these challenges, we propose \textbf{Schrödinger's Navigator}, a navigation framework inspired by Schrödinger's thought experiment on uncertainty. The framework treats unobserved space as a set of plausible future worlds and reasons over them before acting. Conditioned on egocentric visual inputs and three candidate trajectories, a trajectory-conditioned 3D world model imagines future observations along each path. This enables the agent to see beyond occlusions and anticipate risks in unseen regions without requiring extra detours or dense global mapping. The imagined 3D observations are fused into the navigation map and used to update a value map. These updates guide the policy toward trajectories that avoid occlusions, reduce exposure to uncertain space, and better track moving targets. Experiments on a Go2 quadruped robot across three challenging scenarios, including severe static occlusions, unknown risks, and dynamically moving targets, show that Schrödinger's Navigator consistently outperforms strong ZSON baselines in self-localization, object localization, and overall Success Rate in occlusion-heavy environments. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of trajectory-conditioned 3D imagination in enabling robust zero-shot object navigation.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Easy Explanation of “Schrödinger’s Navigator: Imagining an Ensemble of Futures for Zero‑Shot Object Navigation”

1) What is this paper about?

This paper is about teaching a robot to find things (like a chair or a trash can) in a new place it has never seen before. The trick: the robot “imagines” what might be behind walls, furniture, or other blocked areas before it actually goes there. By thinking ahead about several possible futures, it can choose a safer and smarter path.

The name “Schrödinger’s Navigator” comes from Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment about uncertainty. The idea is: when you can’t see something yet, it could be many things at once. So the robot treats hidden areas as multiple possible worlds and plans accordingly.

2) What questions are the researchers trying to answer?

They focus on three simple questions:

- How can a robot find a target object in a brand‑new, cluttered place without special training for that place? (This is called “zero-shot” because there’s no extra training “shot” for the specific environment.)

- How can it handle blocked views (occlusions), unknown dangers, or even targets that move?

- Can imagining different possible futures help the robot pick better routes and succeed more often in the real world?

3) How did they do it? (Methods in simple terms)

Think of a robot searching in a messy room. It can only see what’s in front of it, not what’s behind a table or around a corner. This system helps the robot imagine what it might see if it took different paths, then pick the best one.

Here’s the basic approach, explained with everyday ideas:

- The robot looks around using a camera and depth sensor (depth is like knowing how far things are).

- At each step, it considers three simple detours around an obstacle: go left, go right, or go over/around the top (like taking three possible “routes” around a blockage).

- For each route, a “world model” quickly builds a rough 3D “what you might see” scene, kind of like sketching a future view with lots of tiny soft dots in 3D. This technique is called 3D Gaussian Splatting, but you can think of it as making a fast, fuzzy 3D model out of many small blobs.

- The robot then “aligns” these imagined scenes with its real camera view and depth data so the distances match real life (like stretching or shrinking a drawing so it lines up with a photo).

- It mixes these imagined scenes with what it actually sees to create a decision map—a simple score map—to judge which route is safer, less blocked, and more likely to find the target.

- Finally, it picks the next waypoint (a short-term goal) and moves, repeating the process as it goes.

Why three routes? It’s a good balance: enough variety to peek around occlusions, but still fast so the robot doesn’t waste time thinking too long.

4) What did they find, and why does it matter?

They tested their system on a real robot dog (Unitree Go2) in real indoor places (an office, a classroom, and a common room). They compared against a strong existing system (InstructNav). Here’s what stood out:

- In easy cases with static targets (things that don’t move), both systems did similarly well.

- In harder, more realistic situations, their method worked better:

- For moving targets, they succeeded 16 out of 30 tries vs. 10 out of 30 for the baseline.

- When sudden obstacles appeared, they succeeded 19 out of 30 vs. 12 out of 30 for the baseline.

Why this matters:

- Real-world spaces are messy: things get in the way, and sometimes the object moves. Imagining several possible futures helps the robot avoid dead ends, reduce risk, and find the target more reliably.

- The robot doesn’t need a pre-built map or special training for each new place—useful for homes, offices, or public spaces that are all different.

5) What’s the impact of this research?

This work shows that robots can be smarter and safer by planning with imagination, not just reacting to what they see. Treating hidden areas as “many possibilities” and checking a few likely paths helps:

- Get around occlusions (like tables and walls) more reliably.

- Handle surprises (like a box being dropped in the way).

- Track moving targets better.

In the future, this idea could make home helpers, delivery robots, and service bots more dependable in everyday places. The authors suggest expanding beyond three routes and using even faster, richer 3D imagination tools, which could make robots even more capable in complex, changing environments.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a focused list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, structured to be concrete and actionable for future research.

- Unclear optimality of the tri-trajectory design: why exactly three candidates (left/right/over-top), and under what scene geometries or occlusion patterns does this fixed set fail? Investigate adaptive trajectory sampling strategies that cover plausible futures more comprehensively while respecting compute and robot kinematics.

- Physical feasibility of the “over-the-top” path: for ground robots, vertical bypasses are often infeasible. Quantify the impact of conditioning on physically unreachable viewpoints and develop methods to restrict imagination to kinematically feasible trajectories.

- Missing ablation studies: no systematic analysis of the contribution of each component (trajectory sampler, 3DGS imagination, scale alignment, semantic transfer, multi-sourced vs. future-aware value maps, fusion weighting) to performance.

- No uncertainty quantification of imagined futures: predictions are treated deterministically. Add calibrated uncertainty over geometry and semantics (e.g., per-Gaussian confidence, ensemble or Bayesian world models) and study how uncertainty should modulate planning.

- Reliability of global scale alignment: the median depth ratio method can fail under sparse/invalid depth, reflective surfaces, or misaligned poses. Benchmark robustness and explore multi-view, feature-based, or learned scale estimators with outlier rejection.

- Inconsistency resolution in fused 3DGS scenes: when imagined trajectories produce conflicting geometry/semantics, there is no explicit reconciliation or confidence-weighted fusion strategy. Develop conflict detection and resolution mechanisms.

- Semantic label transfer scope and reliability: it is unclear whether semantics are transferred only from real observations or also from rendered imagined views; label noise and occlusion errors are not quantified. Evaluate open-vocabulary 2D/3D semantics, multi-view fusion policies, and their failure modes.

- Lack of formal hazard modeling: “unknown risks” are mentioned, but hazard categories, detection methods, and risk metrics are not defined. Integrate risk-aware models (e.g., traversability, moving obstacles, unsafe zones) with explicit safety constraints and report safety metrics (near-miss rate, collisions).

- Dependence on Unitree’s native obstacle avoidance: safety outcomes are confounded by external controllers. Isolate the proposed system’s contribution to safety by disabling external avoidance or by controlled comparisons with matched settings.

- Limited evaluation metrics: only Success Rate is reported. Include SPL, path length, time-to-success, collision/near-miss rates, replan counts, energy consumption, and latency to provide a comprehensive assessment of trade-offs.

- Runtime and system latency: world-model inference “within seconds” is not profiled in a closed-loop setting. Quantify per-cycle latency, frequency of imagination, end-to-end throughput, and the impact of remote-server communication on real-time control.

- Compute and deployability constraints: reliance on a remote server and an NVIDIA H800 GPU limits practical deployment. Evaluate on embedded compute (e.g., Jetson), measure energy, and propose incremental or streaming imagination to reduce cost.

- Generalization beyond small indoor spaces: tested in three small indoor scenes with limited clutter dynamics. Stress-test in larger spaces, multi-floor buildings, outdoor scenes, poor lighting, reflective/glassy surfaces, stairs/slopes, and crowded environments.

- Dynamic target realism: dynamic experiments use “pink cubes” rather than real moving objects (humans, pets). Assess tracking and planning with semantically meaningful moving targets exhibiting non-uniform, intent-driven motion.

- Robustness to localization drift: the approach assumes accurate poses. Quantify sensitivity to odometry/IMU drift and evaluate methods to correct or jointly estimate pose within the imagined-fusion loop (e.g., loop closure, pose-graph updates).

- Adaptive horizon and update cadence: no study of how frequently to re-imagine or how long the imagined horizon should be under different dynamics/occlusions. Develop scheduling policies that align imagination cadence with scene change rates and compute budgets.

- Planner integration details: the local/global planner is unspecified and untested across different planners. Evaluate how various planners (sampling-based, graph-based, MPC) interact with the affordance map and which planner features benefit from imagined futures.

- Fusion weighting and hyperparameters: weights such as β, α_sem, α_exp, λ_sem, r_vis are fixed without tuning rationale. Provide sensitivity analyses and automated hyperparameter selection strategies.

- Failure mode characterization: when does imagination harm performance (e.g., hallucinations, misaligned scale, semantic errors)? Quantify and design safeguards (confidence gating, rollback policies, or selective imagination).

- Comparative baselines: comparison is limited to InstructNav. Include ZSON/VLM methods (e.g., ZSON, VLFM, BLIP-based, NavigateDiff, NWM) and scene-completion baselines (predictive occupancy, diffusion predictors) for a fair assessment.

- Reproducibility and openness: reliance on closed GPT-4o and possibly closed FlashWorld models raises reproducibility concerns. Document prompts, seeds, model versions, and release code/configurations or provide open-source equivalents.

- Obstacle detection for trajectory generation: how is the “orbit center” around occluders derived? Provide algorithms to detect occluders, choose orbit parameters, and handle complex obstacle geometries (non-convex, thin structures).

- Handling of multi-agent/crowd scenarios: the paper hints at “multi-robot navigation” but does not address interaction, cooperation, or social compliance. Evaluate in multi-agent settings and incorporate predictive crowd models.

- Semantic goal fidelity: demonstration categories (chair/plant/trash can) differ from motivating examples (e.g., “cat behind table”). Test rare, fine-grained, and deformable categories; evaluate open-world semantic grounding with long-tail distributions.

- Scene memory growth and pruning: 3DGS fusion could accumulate large numbers of Gaussians. Report memory footprint, pruning strategies, and their effects on performance.

- Guarantee of physical consistency: imagined views may be geometrically plausible but not consistent with robot or environment constraints. Incorporate physical feasibility checks (e.g., kinematics, terrain, clearance) into imagination and scoring.

- Learning vs. heuristic fusion: current scoring mixes heuristics and semantic proximity. Explore learned policies that directly consume imagined-future representations, trained with self-supervision or offline datasets for improved decision quality.

- Simulation-to-real and benchmark alignment: no evaluation on standard ObjectNav benchmarks (Habitat, Gibson). Add controlled simulation tests to isolate variables, then validate on real robots to bridge sim-to-real insights.

- Robust scale and pose alignment under partial overlap: develop alignment schemes that handle minimal view overlap, occluded depth, or large viewpoint changes, possibly via feature matching, robust estimators, or jointly optimizing scene and pose.

- Handling long-term dynamics: imagined scenes can quickly become stale as targets move or obstacles reconfigure. Add mechanisms for temporal consistency, change detection, and rapid re-imagination with stateful memory.

- Formalization of “principled” uncertainty reasoning: the approach is pitched as uncertainty-aware but lacks a formal model (e.g., POMDP formulation, belief update). Define the underlying probabilistic framework and analyze performance guarantees.

Practical Applications

Below is an overview of practical, real-world applications that follow directly from the paper’s findings, methods, and innovations—namely, trajectory-conditioned 3D imagination (3DGS), tri-trajectory sampling, and future-aware value maps that enable zero-shot object navigation in occlusion-heavy, uncertain environments. Each item notes sectors, potential tools/products/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies.

Immediate Applications

These applications can be deployed now with currently available components (RGB-D sensors, the paper’s pipeline, existing VLM/LLM backends, and GPU or remote inference).

- Service robots in hospitals and hospitality

- Use case: Occlusion-aware corridor and room navigation; locating and delivering items (e.g., medicines, linens, amenities) while avoiding sudden obstacles and crowds.

- Sector: Healthcare, hospitality robotics.

- Tools/products/workflows: ROS2/Nav2 plugin that wraps the tri-trajectory sampler and the future-aware affordance map; “Schrödinger’s Navigator SDK” for Unitree/Fetch/TurtleBot; remote inference server (FastAPI) with FlashWorld backend and semantic segmentation (e.g., GLEE).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable RGB-D sensing (e.g., RealSense), pose estimation, LLM availability (GPT-4o or equivalent), sufficient compute (H800 GPU or cloud), privacy-compliant data handling in clinical settings.

- Warehouse and logistics robots (aisle search and pick-assist)

- Use case: Zero-shot search for categories (e.g., “find the red box”) behind racks/displays; route selection that anticipates forklifts or pallet jacks.

- Sector: Logistics, retail fulfillment.

- Tools/products/workflows: Warehouse nav stack integration with future-aware value maps; semantic label transfer to link predicted targets to SKU databases.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Adequate indoor lighting, stable depth sensing, semantic models trained on warehouse objects, latency budget compatible with throughput targets.

- Retail floor robots (inspection and restocking assistance)

- Use case: Shelf inspection when items are partially occluded; choosing safer paths around promotional displays or pop-up stands; finding misplaced items.

- Sector: Retail operations.

- Tools/products/workflows: “Occlusion-aware path planner” plugin; periodic future-vision rollouts to inform audit routes; web dashboard for imagined scenes and risk flags.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Segmentation coverage for retail-specific categories, integration with store planograms, acceptable on-prem or cloud inference latency.

- Home assistance robots (object finding and cleaning)

- Use case: “Find the keys/glasses/cat”; navigation in cluttered apartments; safer routes around furniture and children/pets.

- Sector: Consumer robotics.

- Tools/products/workflows: Embedded tri-trajectory sampler with lightweight 3DGS; voice-instruction grounding via LLM (DCoN-style); privacy-centered on-device vision.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust indoor localization without dense global mapping, safe motion constraints for home environments, reliable category recognition.

- Security and facility patrol robots

- Use case: Patrol routes that anticipate occluded corners and dynamic obstacles (e.g., doors opening); prioritizing routes with lower uncertain exposure.

- Sector: Security, property management.

- Tools/products/workflows: Risk-aware value maps with suppression zones; incident logging of imagined futures for auditability.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Policy-compliant sensors, nighttime/degraded-light performance (may need IR or thermal), integration with access control systems.

- Industrial inspection (plants, labs)

- Use case: Navigating around machinery and piping with occlusions; anticipating paths that reduce exposure to hazardous or uncertain areas.

- Sector: Manufacturing, energy, utilities.

- Tools/products/workflows: 3DGS fusion overlaid on digital twins; route validation that weighs semantic targets (gauges, valves) against risk maps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Calibration to facility coordinate frames, PPE-equivalent sensing constraints, model coverage for industrial categories.

- Dynamic target tracking (mobile carts, delivery bots, pets)

- Use case: Follow moving targets while continually re-imagining post-occlusion scenes; maintain line-of-sight with minimal detours.

- Sector: Robotics across service/retail/home.

- Tools/products/workflows: Continuous re-planning loop with future-aware affordance map; teleoperation assistance mode showing imagined views.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust trajectory-conditioned predictions at real-time speeds; smooth handoff between imagined and observed targets.

- Robotics development workflow (“imagination-in-the-loop” planning)

- Use case: Drop-in module for teams to prototype occlusion-aware path planning without task-specific training; compare baselines with imagined futures on standard robots.

- Sector: Software/robotics engineering.

- Tools/products/workflows: ROS2 package with configurable tri-trajectory strategies; test harness that logs SR and occlusion exposure metrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to pretrained world model and segmentation; reproducible evaluation scenes.

- Academic research and teaching

- Use case: Curriculum modules on world-model-based navigation; occlusion-heavy ZSON benchmarks; comparative studies against myopic planners.

- Sector: Academia.

- Tools/products/workflows: Dataset generation protocols using imagined scenes; lab exercises with Unitree or simulated platforms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Availability of the project resources, clear licensing for educational use.

- Procurement and safety validation (policy/ops)

- Use case: Acceptance testing protocols that require “future-aware reasoning” under occlusions (e.g., sudden obstacle drills); risk scoring for deployment environments.

- Sector: Policy, operations, compliance.

- Tools/products/workflows: Standardized SR and hazard-avoidance tests; documentation of imagined trajectories to meet audit requirements.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Organizational buy-in; alignment with local safety regulations; controlled test environments.

Long-Term Applications

These applications will benefit from further research, scaling, or engineering (e.g., broader environment coverage, on-device generative modeling, standards).

- Outdoor micro-mobility and sidewalk delivery robots

- Use case: Occlusion-aware navigation around parked vehicles, street furniture, and crowds; low-uncertainty route selection in cities.

- Sector: Urban mobility, last-mile delivery.

- Tools/products/workflows: Outdoor-capable world models (robust scale alignment, weather invariance); crowd-aware future-value maps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stronger generalization to outdoor lighting/weather, legal frameworks for sidewalk robots, higher-precision localization.

- Aerial drones in complex indoor/outdoor spaces

- Use case: Anticipate occluded regions behind obstacles (beams, foliage); safer routes through dynamic environments.

- Sector: Inspection, agriculture, public safety.

- Tools/products/workflows: MAV-compatible “risk-aware corridors” fused with 3DGS imagination; dynamic path replanning with scale-stable depth fusion.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High-frequency depth/vision under motion, airspace compliance, lightweight on-board inference.

- Disaster response and search-and-rescue

- Use case: Imagining occluded spaces in collapsed structures; reducing exposure to uncertain/hazardous areas; locating victims and exits.

- Sector: Public safety, emergency response.

- Tools/products/workflows: Multimodal sensors (thermal, LiDAR) fused with trajectory-conditioned world models; tri-trajectory ensembles tuned for rubble.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robustness to dust/smoke, limited GPS, unreliable lighting; specialized training data.

- Fleet-level multi-robot coordination

- Use case: Sharing imagined futures to deconflict paths; cooperative coverage of occluded regions; collective uncertainty minimization.

- Sector: Warehousing, hospitals, campuses.

- Tools/products/workflows: Common “world-model API” for shared affordance maps; edge-cloud map fusion services.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable communications, consistent coordinate frames, privacy-preserving map sharing.

- Generalist home agents with on-device imagination

- Use case: End-to-end home assistance (search-and-deliver, tidy-up) using larger ensembles of imagined trajectories without cloud dependence.

- Sector: Consumer robotics.

- Tools/products/workflows: Efficient 3DGS generators on edge accelerators; battery-aware rollout scheduling; fine-grained semantic grounding for household items.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Low-power hardware acceleration, robust local LLM/VLM, privacy and safety by design.

- Construction and facility digital twins

- Use case: Progress monitoring and occlusion-aware path planning that anticipates scaffolding and temporary barriers; risk scoring for worker-robot cohabitation.

- Sector: AEC (architecture, engineering, construction).

- Tools/products/workflows: 3DGS-fused digital twin layers; path validation against evolving site models; compliance dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate and timely site updates, ruggedized sensing, integration with BIM standards.

- Standards and policy for occlusion-aware safety

- Use case: Formalizing “future-aware risk scoring” requirements for public-space robots; audit trails for imagined trajectories and decisions.

- Sector: Regulatory/standards (ISO/ANSI), municipal policy.

- Tools/products/workflows: Conformance tests that quantify occlusion exposure and hazard avoidance; incident reconstruction via imagined scenes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus, liability frameworks, transparent logging.

- Cross-vendor navigation APIs and SDKs

- Use case: Unified “world-model navigation” API that plugs into common stacks (ROS2/Nav2, Isaac), enabling trajectory-conditioned imagination everywhere.

- Sector: Software platforms, robotics OEMs.

- Tools/products/workflows: Vendor-neutral SDK with modules for tri-trajectory sampling, 3DGS fusion, semantic label transfer, and future-aware value maps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Standardized interfaces, licensing of generative backends, long-term maintenance.

- Energy-efficient routing via uncertainty reduction

- Use case: Reducing detours and idle time by preferring routes with lower occlusion and risk; measurable energy savings across fleets.

- Sector: Energy/sustainability in operations.

- Tools/products/workflows: KPI dashboards tracking energy-per-task vs. uncertainty score; route optimization policies informed by imagination.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable metrics tying uncertainty to energy use, real-time optimization under changing conditions.

- Advanced research directions (academia/industry)

- Use case: Larger trajectory ensembles, outdoor-capable 3D generative models, formal guarantees on safety and success under uncertainty.

- Sector: Academia, industrial R&D.

- Tools/products/workflows: Benchmarks for dynamic/occluded navigation; ablation suites for imagination modules; reproducible pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Funding and compute for scaled evaluations; open datasets and standardized protocols.

Notes on common dependencies and feasibility across applications:

- Sensors and calibration: Accurate RGB-D and pose estimation; depth-scale alignment requires overlapping valid pixels between rendered and metric frames.

- Compute and latency: Real-time performance often needs GPU acceleration or optimized edge inference; network connectivity for cloud LLMs/backends.

- Semantics: Target categories must be recognized; segmentation models may need domain-specific fine-tuning.

- Safety and compliance: Motion constraints, obstacle avoidance, and audit logging are critical, especially in public or clinical spaces.

- Robustness: Performance may degrade in extreme lighting, reflective surfaces, dust/smoke, or outdoor conditions without dedicated adaptations.

Glossary

- 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS): A 3D scene representation that uses many Gaussian blobs to render views efficiently and consistently. "3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) scenes"

- Action-landmark pairs (DCoN): A planning representation that sequences actions with intermediate landmarks for navigation. "a time-evolving sequence of action-landmark pairs (DCoN)"

- Affine-invariant world model: A generative model whose outputs are invariant to affine transformations, often lacking absolute metric scale. "FlashWorld is an affine-invariant world model"

- Affordance map: A spatial score map indicating where actions are feasible or advantageous for navigation. "This process produces a final affordance map used for intermediate waypoint selection."

- Conditional diffusion transformer: A model combining diffusion processes with transformer architectures to predict future frames conditioned on inputs. "use a conditional diffusion transformer on egocentric videos"

- Coordinate System Transformation: The process of converting scene data between local and global coordinate frames to ensure alignment. "Coordinate System Transformation."

- Depth-consistency check: A validation step ensuring predicted depths align with measured depths to avoid label errors. "depth-consistency check"

- Egocentric visual inputs: First-person visual observations captured from the agent’s viewpoint. "Conditioned on egocentric visual inputs and three candidate trajectories,"

- Frontier maps (Vision-language frontier maps): Maps that mark boundaries between explored and unexplored regions, enhanced with vision-language semantics. "vision-language frontier maps"

- Gaussian primitives: The individual Gaussian components that constitute a 3DGS scene. "lift 2D semantic predictions from the image plane to the Gaussian primitives."

- Global Scale Alignment: Estimating and applying a global scale factor to match generated scenes to metric measurements. "Global Scale Alignment."

- Heuristic guidance map: A map encoding heuristic preferences to bias navigation decisions. "heuristic guidance map "

- LLM: A powerful LLM used for high-level reasoning and navigation planning. "we first apply a LLM"

- Navigation World Models (NWM): Generative models tailored to predict navigational futures from egocentric data. "Navigation World Models (NWM) use a conditional diffusion transformer on egocentric videos"

- P-ObjectNav: A variant of ObjectNav focused on portable or dynamic targets. "Portable Targets (P-ObjectNav)"

- Pinhole projection function: The mathematical mapping from 3D points to 2D image coordinates using camera intrinsics. "be the pinhole projection function"

- Semantic Label Transfer: Assigning semantic labels from 2D segmentation to 3D Gaussian elements. "Semantic Label Transfer."

- Semantic segmentation: Pixel-level classification of an image into semantic categories. "off-the-shelf semantic segmentation network"

- Sim-to-real transfer: Adapting methods trained in simulation to perform reliably in real-world settings. "sim-to-real transfer"

- Trajectory-conditioned 3D world model: A world model that predicts future observations conditioned on candidate trajectories. "a trajectory-conditioned 3D world model imagines future observations along each path."

- Trajectory suppression map: A map that penalizes or suppresses undesirable trajectories during planning. "trajectory suppression map "

- Value map: A score map used to guide navigation decisions based on current and imagined observations. "used to update a value map"

- Vision-LLMs (VLMs): Pretrained models that align visual and textual information for zero-shot reasoning. "vision-LLMs (VLMs)"

- World coordinate frame: The global reference frame in which robot poses and scene geometry are defined. "world coordinate frame"

- Zero-shot object navigation (ZSON): Finding a specified object in new environments without task-specific training. "Zero-shot object navigation (ZSON) requires a robot to locate a target object in a previously unseen environment"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.