What matters for Representation Alignment: Global Information or Spatial Structure? (2512.10794v1)

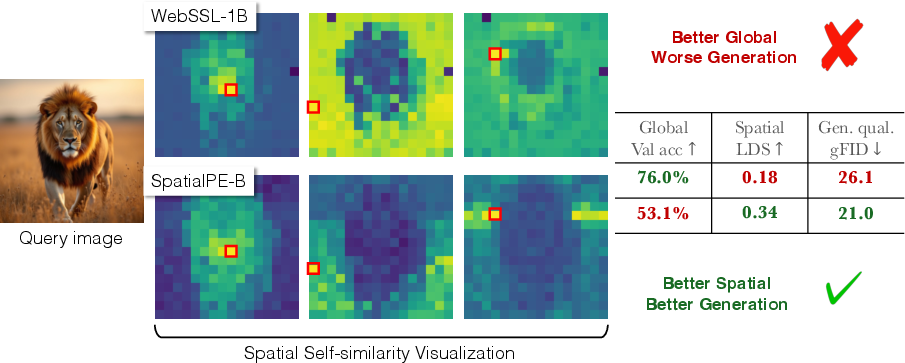

Abstract: Representation alignment (REPA) guides generative training by distilling representations from a strong, pretrained vision encoder to intermediate diffusion features. We investigate a fundamental question: what aspect of the target representation matters for generation, its \textit{global} \revision{semantic} information (e.g., measured by ImageNet-1K accuracy) or its spatial structure (i.e. pairwise cosine similarity between patch tokens)? Prevalent wisdom holds that stronger global semantic performance leads to better generation as a target representation. To study this, we first perform a large-scale empirical analysis across 27 different vision encoders and different model scales. The results are surprising; spatial structure, rather than global performance, drives the generation performance of a target representation. To further study this, we introduce two straightforward modifications, which specifically accentuate the transfer of \emph{spatial} information. We replace the standard MLP projection layer in REPA with a simple convolution layer and introduce a spatial normalization layer for the external representation. Surprisingly, our simple method (implemented in $<$4 lines of code), termed iREPA, consistently improves convergence speed of REPA, across a diverse set of vision encoders, model sizes, and training variants (such as REPA, REPA-E, Meanflow, JiT etc). %, etc. Our work motivates revisiting the fundamental working mechanism of representational alignment and how it can be leveraged for improved training of generative models. The code and project page are available at https://end2end-diffusion.github.io/irepa

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Explaining “What matters for Representation Alignment: Global Information or Spatial Structure?”

What’s this paper about?

This paper looks at a training trick for image generators called diffusion models. The trick is called “representation alignment” (REPA). Think of it like this: a big, smart “vision” model (the teacher) knows a lot about images. A generator (the student) tries to learn from that teacher by matching its own internal features to the teacher’s features. The question the paper asks is: which part of the teacher’s knowledge is most helpful for training better image generators?

- Is it global information (like “this picture has a dog and a tree”)?

- Or is it spatial structure (how different parts of the image relate to each other in space, like “this patch is near that patch and they fit together”)?

The surprising answer: spatial structure matters much more than global information.

Key objectives in simple terms

The researchers set out to:

- Test whether “global smarts” (being good at labeling what’s in a whole image) or “spatial smarts” (knowing how parts of an image connect and differ across locations) better improve image generation.

- Measure which kind of teacher features predict good results for generators.

- Try tiny, simple changes to REPA that boost the flow of spatial information—and see if that speeds up training.

How did they study it?

They ran a large set of experiments and a few clean “what-if” tests.

Big comparison across many teacher models

- They tested 27 different vision models as teachers (small to huge ones).

- For each teacher, they trained the same type of diffusion generator and checked how good the generated images looked.

How they measured things (with easy analogies)

- Global information: They used a simple test called “linear probing” that checks how well the teacher’s features can recognize objects in photos (like ImageNet accuracy). High score = great at identifying what’s in the picture.

- Spatial structure: They looked at how similar or different small image pieces (patches) are to each other based on their distance in the image. If nearby patches are more similar than far-away patches, that’s strong spatial structure. You can think of this as: do the puzzle pieces fit well together because the teacher keeps location and relationships clear?

- Generation quality: They used FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) and other scores to judge how realistic and varied the generated images are. Lower FID is better.

Controlled tests (simple, clear checks)

- They mixed more “global” info into patch features and saw if generation improved or not.

- They tried teachers with very low global accuracy (poor at labeling images) to see if generation still benefited.

- They also tried old-school spatial features like SIFT and HOG to see if even basic spatial signals help.

A small upgrade to REPA: iREPA

They made two very small changes—just a few lines of code—to help the student copy spatial structure better:

- Replace an MLP with a convolution:

- Before: an MLP (a mixing layer) maps student features to teacher features but doesn’t naturally care about who’s next to whom.

- After: a tiny 3×3 convolution looks at neighbors on the grid, so local spatial relationships are preserved.

- Add spatial normalization to the teacher features:

- Patch features often carry a strong global “average” signal that makes patches look too similar everywhere.

- Spatial normalization removes this global average (and scales by local variation), which boosts contrast between patches in different places—making the “layout” signal clearer.

These two together are called iREPA.

Main findings

Here are the main results explained in everyday language:

- Better labelers aren’t always better teachers for generation.

- Teachers with higher image recognition scores did not consistently lead to better image generation. In fact, some high-accuracy teachers produced worse results.

- Spatial structure predicts image quality much better than global scores.

- When the teacher’s features keep nearby parts of the image more similar than distant parts, the generator does better. This correlation was strong across many models and sizes.

- Adding extra global info can hurt generation.

- Making every patch more like the global “summary” (for example, by mixing in a CLS token) improved recognition scores but made generation worse. Why? Because it reduces spatial contrast—the patches start to look too similar across the image.

- Even simple spatial features help.

- Old methods like SIFT and HOG, which mainly care about edges and local patterns, still provided useful boosts when used in alignment—showing spatial cues alone can be valuable.

- A tiny change speeds things up: iREPA works consistently.

- Replacing the projection MLP with a small convolution and normalizing patches to boost spatial contrast helped the generator learn faster and reach better scores across many teachers, model sizes, and training recipes (like REPA, REPA-E, MeanFlow with REPA, and even pixel-space models like JiT).

Why this matters

- Choose teachers for the right reason: If you’re training image generators, pick or design teacher models with strong spatial structure—not just high image classification accuracy.

- Faster, better training: Small, simple changes (iREPA) make alignment more effective, improving convergence speed and final quality.

- Rethink what “good features” mean for generation: For creating images, understanding how parts fit together across the image is more important than just knowing the overall category.

- Future model design: This work encourages building or tuning teacher encoders that keep sharp, location-aware signals—great for generators that need to “compose” images from many small parts.

A simple analogy to remember

Imagine building a jigsaw puzzle:

- Global information is the box cover: it tells you it’s a picture of a dog in a park.

- Spatial structure is how the puzzle pieces fit: which edges match, which colors continue, and where each piece belongs. This paper shows that, for training image generators, having pieces that fit together well (spatial structure) matters more than just seeing the box cover (global label knowledge). iREPA helps the student learn the “how pieces fit” part better and faster.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise, action-oriented list of what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper.

- Causality vs. correlation: The paper establishes high Pearson correlations between spatial structure metrics (SSM) and generation FID but does not demonstrate causal relationships (e.g., via interventions that isolate spatial structure while holding global semantics constant beyond CLS mixing).

- Confounders in correlation analysis: No multivariate regression or partial correlation controlling for encoder patch size, token dimensionality, positional encoding schemes, normalization layers, training hyperparameters, or data augmentations—any of which could inflate SSM–FID correlations.

- Dataset scope: All core results are on ImageNet at 256×256; generalization to other datasets (e.g., COCO, LAION, Places, fashion, medical) and higher resolutions (512×512, 1024×1024) is not evaluated.

- Task scope: The paper focuses on class-conditional or unconditional image generation; impact on text-to-image generation, compositional controllability, fine-grained attribute adherence, and instruction following is unknown.

- Final quality vs. convergence speed: iREPA is shown to accelerate convergence; whether it consistently improves or harms ultimate performance at long training budgets (beyond 400K steps) is not systematically assessed.

- Metric discrepancies: sFID sometimes worsens while FID improves (and vice versa); the paper does not analyze why spatial accentuation yields mixed effects across different quality/diversity metrics (FID, sFID, IS, precision/recall).

- Semantic fidelity trade-offs: Spatial normalization explicitly suppresses global components; the impact on semantic alignment (e.g., class consistency, identity preservation, label accuracy) is not quantified for the generated samples.

- Precision–recall dynamics: Although precision and recall are reported, there is no detailed analysis of how iREPA shifts the quality–diversity trade-off or whether improvements come from mode collapse mitigation or better coverage.

- Encoder diversity and representational families: The 27 encoders are not fully enumerated and do not clearly include standard supervised CNNs (e.g., ResNet) or tokenization schemes beyond ViTs; broader conclusions may not generalize.

- SSM design and sensitivity: The LDS/CDS/SRSS/RMSC metrics lack a thorough sensitivity analysis (e.g., choice of , , lattice distance definition, cosine vs. other kernels, Manhattan vs. Euclidean distance), and their robustness across datasets is untested.

- Positional encoding effects: How positional embeddings (absolute/relative, learned/sinusoidal) in both teacher and student affect spatial self-similarity and the success of REPA/iREPA is unexplored.

- Layer-wise alignment strategy: Beyond shallow analyses of “alignment depth,” the paper does not explore multi-layer alignment schedules, cross-layer mixing, or dynamic layer selection based on SSM during training.

- Projection-head alternatives: Only a single small 3×3 conv is studied; other locality-preserving heads (depthwise separable convs, deformable convs, graph operators, attention-based mapping) and their trade-offs remain unexplored.

- Normalization choices and schedules: The spatial normalization uses an InstanceNorm-like formulation with fixed ; its optimal value, scheduling, layer placement, and comparisons to GroupNorm/LayerNorm or whitening are not studied.

- Architectural breadth: Evaluation is limited to SiT variants and JiT-B; generalization to other diffusion architectures (U-Nets with attention, rectified flows, consistency models, autoregressive decoders) is untested.

- Training hyperparameters: The paper does not investigate whether iREPA requires different learning rates, optimizers, weight decay, or augmentation strategies to be stable across encoders and datasets.

- Computational overhead and memory: The runtime, memory footprint, and throughput impact of iREPA’s conv projection and normalization are not measured; potential bottlenecks for large-scale training are unknown.

- Resolution and token-grid assumptions: iREPA’s conv projection presumes a regular spatial grid; applicability to encoders producing irregular tokens (e.g., region proposals, deformable tokens) or variable token counts is unclear.

- SIFT/HOG baselines: Claims that classical features (SIFT/HOG/VGG) can drive REPA gains are anecdotal; quantitative comparisons, ablations, and scalability under identical training settings are missing.

- Teacher selection policy: While SSM correlates with FID, the paper does not propose or validate a principled, automated strategy to select teachers based on SSM, including cross-dataset SSM estimation and variance considerations.

- In-training diagnostics: Real-time tracking of the student’s spatial structure (SSM) and its predictive power for convergence is not provided; using SSM as a training signal or early-stopping criterion remains unexplored.

- Noise schedule and sampling: Interactions between spatial accentuation and diffusion noise schedules, timesteps, and samplers (DDIM, DPM-Solver, MeanFlow variants) are not analyzed beyond limited NFE tests.

- CFG interactions: While some CFG results are reported, the effect of spatial accentuation on CFG tuning (scale, classifier conditioning quality) and potential shifts in guidance optimality is not deeply studied.

- Failure modes: The paper does not catalog cases where spatial accentuation degrades quality (e.g., overly homogenized textures, loss of global coherence), nor does it offer diagnostics or mitigations.

- Broader modalities: Extension to video/3D/audio generation is only mentioned in related work; whether spatial structure dominance holds for spatiotemporal or multimodal alignment is an open question.

- Theory/mechanism: No theoretical account explains why spatial structure should dominate REPA’s efficacy; a formal model or mutual information analysis between token neighborhoods and pixel-space likelihoods would strengthen the claims.

- Hybrid strategies: Whether combining spatial accentuation early with global semantics later (curriculum), or selectively preserving global information in certain layers, yields superior outcomes is untested.

- Robustness to domain shifts: The stability of SSM–FID correlations under distribution shift (e.g., out-of-domain test sets, corrupted/augmented inputs) and the robustness of iREPA under such conditions remain unknown.

Glossary

- Accentuating spatial features: Emphasizing the transfer of local, spatial information during training to improve generation. "Accentuating spatial features helps consistently improve convergence speed."

- C-RADIO: A family of pretrained vision encoders referenced as strong external representations. "including recent large vision foundation models such as WebSSL \citep{fan2025scaling}, DINOv3 \citep{simeoni2025dinov3}, perceptual encoders \citep{bolya2025PerceptionEncoder}, C-RADIO \citep{heinrich2025radiov25improvedbaselinesagglomerative}, we uncover 3 surprising findings."

- CLS token: The classification token in Vision Transformers that aggregates global information across patches. "Adding global information to patch tokens via CLS token hurts generation."

- Classifier-free guidance (CFG): A sampling technique that improves conditional generation without an auxiliary classifier. "We evaluate the generation quality of iREPA with CFG in Table~\ref{tab:system_results}."

- Convolutional projection layer: A spatially aware projection (e.g., 3×3 conv) replacing an MLP to better preserve local structure. "We replace the standard MLP projection layer in REPA with a simple convolution layer and introduce a spatial normalization layer for the external representation."

- Correlogram: A contrast-based metric comparing local vs. distant similarities across spatial locations. "By default, we use a simple correlogram contrast (local vs.\ distant) metric \citep{huang1997correlogram}:"

- Cosine kernel: A kernel measuring similarity via the cosine of the angle between feature vectors. "Here, we use the cosine kernel"

- Cosine similarity: The similarity measure between two vectors given by the cosine of the angle between them. "its spatial structure (i.e. pairwise cosine similarity between patch tokens)?"

- Correlation analysis: Statistical analysis quantifying relationships between variables (e.g., spatial metrics and FID). "Correlation analysis across 27 diverse vision encoders, SiT-XL/2 and REPA."

- DINOv2: A self-supervised Vision Transformer encoder used as a target representation. "Notably \citep{repa} also make a similar observation for DINOv2 and explain it as ``we hypothesize is due to all DINOv2 models being distilled from the DINOv2-g model and thus sharing similar representations''."

- DINOv3: A more recent self-supervised Vision Transformer encoder. "We examine different recent vision encoders, including Perceptual Encoders \citep{bolya2025PerceptionEncoder}, WebSSL \citep{fan2025scaling}, and DINOv3 \citep{simeoni2025dinov3}."

- Diffusion transformer: A transformer-based generative diffusion model architecture. "Representation alignment has emerged as a powerful technique for accelerating the training of diffusion transformers \citep{sit, dit}."

- Distilling representations: Transferring knowledge from a pretrained encoder to another model’s intermediate features. "Representation alignment (REPA) guides generative training by distilling representations from a strong, pretrained vision encoder to intermediate diffusion features."

- FID (Fréchet Inception Distance): A metric evaluating the quality of generated images via distributional similarity to real images. "the model not only captures better semantics but also exhibits enhanced generation performance, as reflected by improved validation accuracy with linear probing and lower FID scores."

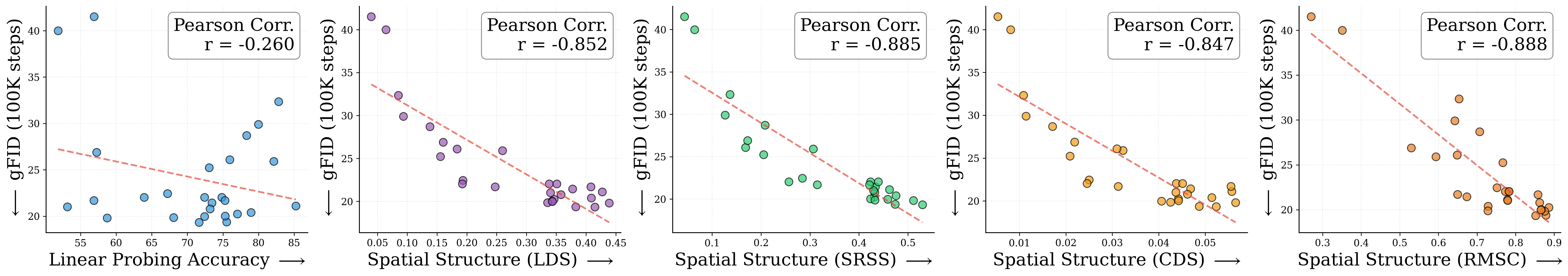

- gFID: Generation FID; FID specifically used to measure generation quality in this work. "Across different model scales, we find that spatial structure (right) consistently shows higher correlation with gFID than linear probing (left)."

- ImageNet-1K accuracy: Validation accuracy on the ImageNet-1K benchmark, used as a proxy for global semantic performance. "is that encoder performance for representation alignment correlates strongly with ImageNet-1K validation accuracy, a proxy measure of global semantic understanding \citep{dinov2, chen2021empirical}."

- Inductive bias: Built-in assumptions of a model (e.g., locality in convolutions) that guide learning. "The convolutional structure naturally preserves local spatial relationships through its inductive bias."

- iREPA: A simple, improved representation alignment recipe that accentuates spatial information transfer. "Surprisingly, our simple method (implemented in 4 lines of code), termed iREPA, consistently improves convergence speed of REPA, across a diverse set of vision encoders, model sizes, and training variants (such as REPA, REPA-E, Meanflow, JiT etc)."

- JiT: A pixel-space diffusion model used to test representation alignment variants. "Convergence comparison with pixel-space diffusion (JiT)."

- Linear probing: Evaluating feature quality by training a linear classifier on frozen representations. "Linear probing shows weak correlation across model scales (), while spatial structure shows much higher correlation with generation performance ()."

- Manhattan distance: The L1 distance measure on a grid used to compute token pair distances. "and be the Manhattan distance between pairs of tokens."

- MeanFlow: A sampling/training variant used with REPA to evaluate convergence and quality. "Lastly, we analyze the generalization of iREPA across different training recipes such as REPA-E~\citep{repae} and MeanFlow w/ REPA \citep{meanflow}."

- MLP projection layer: A multi-layer perceptron used to map diffusion features to the target representation’s dimension. "We replace the standard MLP projection layer in REPA with a simple convolution layer and introduce a spatial normalization layer for the external representation."

- NFE (Number of Function Evaluations): The number of solver steps used during diffusion sampling. "#1{All results are reported w/o classifier free guidance, SiTXL/2 w/ REPA and 250 NFE \citep{repa} for inference.}"

- Patch tokens: Token embeddings corresponding to local patches in ViT-like encoders. "we use linear probing accuracy on patch tokens to measure global semantic performance of external representation as only patch tokens are used for representation alignment."

- Pearson correlation: The Pearson correlation coefficient quantifying linear relationships between variables. "Linear probing shows weak correlation with FID (Pearson ), while all spatial structure metrics: LDS (), SRSS (), CDS (), and RMSC (), demonstrate much stronger correlation with generation performance."

- Perceptual Encoder (PE): A family of encoders tuned for perceptual and spatial tasks (e.g., PE-Core-G, PE-Spatial-B). "Consider PE-Spatial-B (80M), a small spatially tuned model derived from PE-Core-G (1.88B) \citep{bolya2025PerceptionEncoder}."

- Pixel-space diffusion: Diffusion models operating directly on pixels rather than latent spaces. "We also evaluate iREPA on pixel-space diffusion models such as JiT-B~\citep{li2025back}."

- REPA: Representation alignment method that matches diffusion features to an external vision encoder’s features. "Representation alignment (REPA) guides generative training by distilling representations from a strong, pretrained vision encoder to intermediate diffusion features."

- REPA-E: An enhanced variant of REPA used to test the generality of spatial improvements. "Does iREPA generalize across more recent representation alignment methods such as REPA-E \citep{repae}, MeanFlow w/ REPA \citep{meanflow}?"

- Representation alignment: Training strategy aligning internal diffusion representations to pretrained encoder features. "Representation alignment has emerged as a powerful technique for accelerating the training of diffusion transformers \citep{sit, dit}."

- RMSC: A spatial structure metric used to assess how token similarity varies with distance. "RMSC ()"

- SAM2: A segmentation model’s vision encoder used as a target representation for REPA. "SAM2 outperforms vision encoders with much higher ImageNet-1K accuracy."

- SIFT: Scale-Invariant Feature Transform; a classical local feature used to test spatial-only alignment. "If spatial structure matters more, can we use SIFT or HOG features for REPA? Surprisingly, yes."

- SiT-XL/2: A specific diffusion transformer model scale used throughout experiments. "All results reported at 100K using SiT-XL/2 and REPA."

- Spatial normalization layer: Normalization across the spatial dimension to reduce global components and increase local contrast. "we add a simple spatial normalization layer \citep{ulyanov2016instance} to the patch tokens of the target representation:"

- Spatial regularization layer: A layer that increases spatial contrast in target representations before alignment. "We first introduce a spatial regularization layer which boosts the spatial contrast of the target representations."

- Spatial Self-Similarity: The property that nearby patches have higher similarity than distant ones. "Spatial Self-Similarity: We find that spatial structure instead provides a better predictor of generation quality than global performance."

- Spatial Structure Metric (SSM): An aggregate metric family (e.g., LDS, SRSS, CDS, RMSC) that quantifies spatial organization in representations. "We introduce a straightforward and fast-to-compute Spatial Structure Metric (SSM), which shows significantly higher correlation with downstream FID performance than linear probing scores."

- SRSS: A spatial structure metric used in correlation analyses alongside LDS, CDS, and RMSC. "SRSS ()"

- VGG: A convolutional network whose intermediate features are used as classical spatial representations. "intermediate VGG features \citep{vgg} all lead to performance gains with REPA."

- WebSSL: A large-scale self-supervised vision foundation model used as a target representation. "Similarly, WebSSL-1B~\citep{fan2025scaling} also shows much better global performance (76.0\% vs.\ 53.1\%), but worse generation."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

Below are actionable use cases that can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s findings that spatial structure—rather than global semantic performance—drives representation alignment, and the iREPA improvements (conv projection + spatial normalization) that consistently accelerate convergence.

- Drop-in training speedups with iREPA

- Sectors: software/AI platforms, VFX/media, gaming, e-commerce imagery, robotics simulation

- Tools/workflows: integrate the 3×3 conv projection and spatial normalization into existing REPA/REPA‑E/MeanFlow/JiT pipelines; update training templates in internal ML platforms

- Expected outcomes: fewer training steps to reach target FID/IS; lower compute spend; faster iteration cycles

- Assumptions/dependencies: access to training code; compatibility with patch-token encoders; mild hyperparameter tuning (e.g., normalization strength γ)

- Encoder selection based on spatial self-similarity (SSM) rather than ImageNet accuracy

- Sectors: software/AI, VFX/media, robotics, education/research

- Tools/workflows: an

SSM Scorecardscript to rank candidate encoders (e.g., DINOv3, PE variants, SAM2) by LDS/CDS/SRSS/RMSC; an encoder-selection dashboard integrated into MLOps - Expected outcomes: better generation quality for the same or lower cost; surprising wins with smaller spatially-tuned encoders (e.g., SAM2, PE‑Spatial)

- Assumptions/dependencies: ability to run candidate encoders to extract patch tokens; domain transfer validity beyond ImageNet; tokenization and patch size consistency

- Training rule-of-thumb: avoid inflating patch tokens with CLS/global components

- Sectors: software/AI training teams, academia

- Tools/workflows: disable CLS mixing into patch tokens; apply spatial normalization to teacher features to preserve spatial contrast

- Expected outcomes: stronger spatial signals and improved FID despite lower linear probing scores

- Assumptions/dependencies: tasks are generation-centric rather than classification-centric; text-to-image prompt adherence is monitored (global semantics may be reduced)

- Pixel-space diffusion gains (JiT + iREPA)

- Sectors: imaging pipelines for super-resolution, restoration, and pixel-space diffusion products

- Tools/workflows: plug iREPA into JiT training; use SSM metrics to predict convergence behavior

- Expected outcomes: consistent convergence speedups; reduced iteration time for pixel-space models

- Assumptions/dependencies: JiT training code access; compatible feature alignment layers; CFG settings tuned for product use cases

- Low-resource regimes: use classical spatial features (SIFT/HOG/VGG mid-layer) as teacher representations

- Sectors: education, startups, embedded systems

- Tools/workflows: REPA with classical features when large foundation encoders are unavailable; quick prototyping courses/labs

- Expected outcomes: “good enough” convergence gains with minimal compute

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-specific quality targets may be modest; classical features’ performance varies by dataset

- Compute/energy savings and sustainability tracking

- Sectors: finance (cost control), sustainability/ESG, cloud/HPC ops

- Tools/workflows: “steps-to-target-FID” KPI; cost calculators that quantify energy/carbon savings from iREPA vs REPA; procurement planning based on improved sample efficiency

- Expected outcomes: lower spend per training run; measurable green AI benefits

- Assumptions/dependencies: target quality metrics (FID/IS/sFID) fixed; actual savings depend on hardware and dataset size

- Model cards and internal governance: report SSM alongside standard metrics

- Sectors: policy/compliance, AI governance, academia

- Tools/workflows: add SSM plots and scores to encoder/model cards; use SSM trends to justify encoder choices and alignment depth

- Expected outcomes: more informative documentation; better internal reviews and reproducibility

- Assumptions/dependencies: organizational acceptance of non-standard metrics; SSM computation integrated into CI

- Robotics/simulation data generation with stronger spatial fidelity

- Sectors: robotics, autonomous systems, digital twins

- Tools/workflows: choose spatial-high encoders; apply iREPA to generative scene synthesis pipelines for better geometric coherence

- Expected outcomes: improved structural consistency in synthetic training data; reduced sim-to-real gap

- Assumptions/dependencies: downstream tasks value spatial coherence; careful validation for control tasks

- Medical imaging R&D (non-clinical) prototypes

- Sectors: healthcare research, medical imaging startups

- Tools/workflows: use spatial-first encoders and iREPA to prototype generative augmentation that preserves anatomy (e.g., organs’ spatial relations)

- Expected outcomes: better structural fidelity in synthetic data for research

- Assumptions/dependencies: non-clinical experimentation only; domain metrics beyond FID/IS are required; compliance and safety reviews needed before any clinical use

- End-user impact via product teams: faster model refreshes for creative apps

- Sectors: consumer creative apps, enterprise design tools

- Tools/workflows: internal training pipelines updated with iREPA; quicker release cycles of improved image generators

- Expected outcomes: end-users see quality improvements sooner; reduced latency for new model versions

- Assumptions/dependencies: backend training owned by product org; existing generator relies on REPA-like alignment

Long-Term Applications

These use cases require further research, scaling, and/or validation to realize their full potential.

- Spatial-first foundation encoders optimized for generative alignment

- Sectors: software/AI, foundation model providers

- Tools/products: new encoder families tuned to maximize SSM (LDS/SRSS/CDS/RMSC) while maintaining enough global semantics for controllability

- Potential workflows: encoder pretraining regimes that explicitly regularize spatial contrast; evaluator suites that combine SSM and generative performance predictors

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust generalization across modalities and datasets; careful trade-offs with text/prompt adherence

- AutoML for representation alignment

- Sectors: MLOps platforms, AutoML vendors

- Tools/products:

Auto-REPAthat searches for the best teacher encoder, alignment depth, projection type, and normalization strength (γ), guided by SSM and early FID slope - Potential workflows: closed-loop tuning that monitors SSM of teacher and student features during training

- Assumptions/dependencies: reliable on-the-fly SSM estimators; scalable search over encoders and alignment configurations

- Cross-modal extensions: video and 3D generative training with spatial signal emphasis

- Sectors: video editing/VFX, AR/VR, 3D content, robotics simulation

- Tools/products:

Video-iREPAand3D-iREPAvariants that align spatiotemporal features and 3D token grids; spatial normalization adapted to time and depth dimensions - Potential workflows: improved sample efficiency in video diffusion; geometry-aware 3D generation

- Assumptions/dependencies: stable spatiotemporal/3D tokenization; domain-specific metrics (e.g., temporal consistency, mesh fidelity)

- On-device/edge personalization enabled by improved sample efficiency

- Sectors: mobile, IoT, creative tools

- Tools/products: lightweight encoders with high SSM; edge-friendly iREPA variants that reduce training steps for user personalization

- Potential workflows: short personalization sessions for style/domain adaptation; periodic background fine-tuning

- Assumptions/dependencies: memory and compute constraints on device; privacy and energy considerations

- Policy and standards: reporting efficiency and spatial structure in model governance

- Sectors: policy/regulatory, AI standards bodies, sustainability/ESG

- Tools/products: standards for “Green GenAI” model cards including steps-to-target-FID, energy use, SSM scores; procurement guidelines that encourage spatial-first encoders for generative training

- Potential workflows: compliance auditing that verifies declared efficiency gains

- Assumptions/dependencies: consensus on SSM definitions; broad adoption across industry and academia

- Safety and controllability research: balancing spatial structure with global semantic guidance

- Sectors: text-to-image platforms, safety teams

- Tools/workflows: hybrid normalization that preserves spatial contrast while retaining prompt adherence; dynamic gating of global components during training

- Potential outcomes: improved controllable generation without sacrificing structural fidelity

- Assumptions/dependencies: robust prompt-following benchmarks; nuanced metrics beyond FID/IS

- Healthcare (clinical) applications with domain-level validation

- Sectors: clinical imaging, radiology

- Tools/products: generative augmentation pipelines that emphasize structural consistency for lesion detection/segmentation training

- Potential workflows: clinical trials and regulatory submissions; domain metrics (e.g., Dice, Hausdorff) as primary targets

- Assumptions/dependencies: rigorous validation and approvals; alignment to DICOM and privacy standards; bias and safety audits

- Industry-wide “Encoder Marketplace” and benchmarking

- Sectors: AI tooling vendors, cloud marketplaces

- Tools/products: catalogs that rank encoders by SSM, generative FID/IS, and efficiency profiles; plug-and-play teacher selection for REPA-like training

- Potential workflows: subscription-based access to curated teacher models with performance guarantees

- Assumptions/dependencies: standardized evaluation suites; licensing and IP clarity for pretrained encoders

- Dynamic spatial normalization and projection architectures

- Sectors: research labs, model architecture teams

- Tools/products: adaptive normalization layers that tune γ per mini-batch/domain; learned projection operators that preserve spatial relationships without degrading global control

- Potential workflows: continuous monitoring of student feature spatial structure to drive layer updates

- Assumptions/dependencies: stability under adaptive strategies; interpretability of spatial signals in complex pipelines

- Robotics world-model training with spatially aligned generators

- Sectors: robotics, autonomous navigation/manipulation

- Tools/workflows: generative world models trained with iREPA to better preserve geometry/topology; synthetic data that improves downstream planning and perception

- Potential outcomes: reduced real-world data collection costs; safer sim-to-real transfer

- Assumptions/dependencies: domain-specific metrics and validation; integration with control/learning stacks; robustness under distribution shift

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.