Dataset Distillation for Pre-Trained Self-Supervised Vision Models (2511.16674v1)

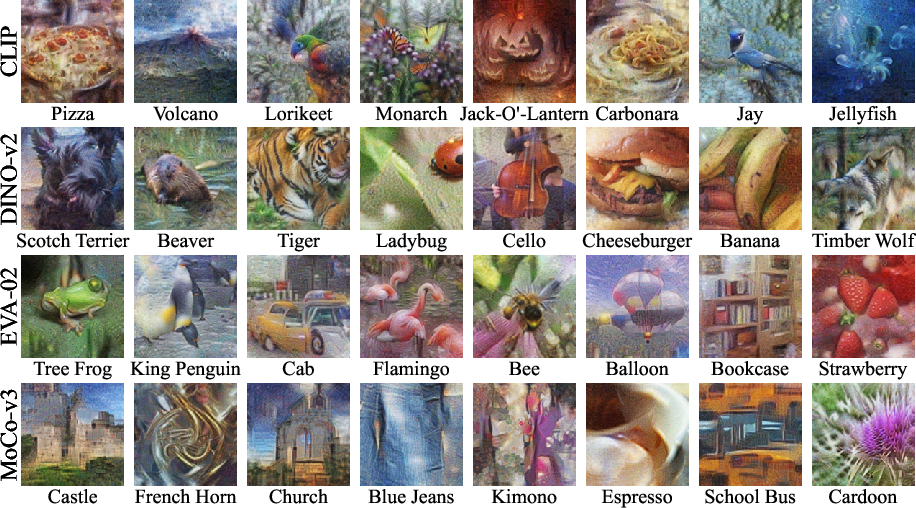

Abstract: The task of dataset distillation aims to find a small set of synthetic images such that training a model on them reproduces the performance of the same model trained on a much larger dataset of real samples. Existing distillation methods focus on synthesizing datasets that enable training randomly initialized models. In contrast, state-of-the-art vision approaches are increasingly building on large, pre-trained self-supervised models rather than training from scratch. In this paper, we investigate the problem of distilling datasets that enable us to optimally train linear probes on top of such large, pre-trained vision models. We introduce a method of dataset distillation for this task called Linear Gradient Matching that optimizes the synthetic images such that, when passed through a pre-trained feature extractor, they induce gradients in the linear classifier similar to those produced by the real data. Our method yields synthetic data that outperform all real-image baselines and, remarkably, generalize across pre-trained vision models, enabling us, for instance, to train a linear CLIP probe that performs competitively using a dataset distilled via a DINO backbone. Further, we show that our distilled datasets are exceptionally effective for fine-grained classification and provide a valuable tool for model interpretability, predicting, among other things, how similar two models' embedding spaces are under the platonic representation hypothesis or whether a model is sensitive to spurious correlations in adversarial datasets.

Sponsor

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about (the big idea)

Imagine shrinking a huge photo dataset (like a giant textbook) into a tiny set of made‑up pictures (like powerful flashcards) that can teach a computer just as well. This paper shows how to create those “flashcard” images for modern vision systems that already learned a lot from the internet without labels (self‑supervised models like CLIP or DINO). The goal is to train a simple final classifier on top of those models using only one synthetic image per class—and still do really well.

What questions did the researchers ask?

- Can we invent a very small set of synthetic images so that, when used to train a simple classifier (a “linear probe”) on top of a big pre‑trained vision model, we get almost the same accuracy as if we had trained with tons of real photos?

- Can those tiny synthetic datasets work not just for the model they were made with, but also for other models (cross‑model generalization)?

- Can these synthetic images help us understand what different models pay attention to (for example, whether a model focuses on backgrounds instead of the actual object)?

- Are these distilled images especially helpful on hard tasks where classes look very similar (fine‑grained classification, like dog breeds or bird species)?

How they did it (in everyday terms)

Think of a pre‑trained vision model as a really good “feature finder” that turns an image into a useful set of numbers (features) describing shapes, textures, and patterns. On top of that, we train a simple classifier (a linear probe) that just draws boundaries between classes using those features.

The trick: create synthetic images that “teach” the classifier in the same way real images do.

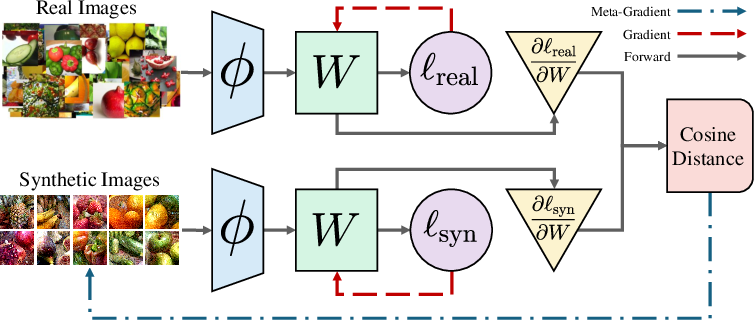

- Gradients as teaching directions: When training, the classifier looks at errors and figures out which direction to adjust itself—that direction is called a gradient. If two different training sets give similar gradients, they’re teaching the same lesson.

- Gradient matching: The method, called Linear Gradient Matching, tweaks the pixels of the synthetic images so that, after passing through the pre‑trained feature finder, they make the classifier want to change in almost the exact same direction as it would with real images.

- Random classifier during distillation: To avoid overfitting to one specific classifier, they re‑roll a random linear probe each step, compare the “teaching directions” (gradients) from real vs. synthetic data, and push the synthetic images to make those directions line up.

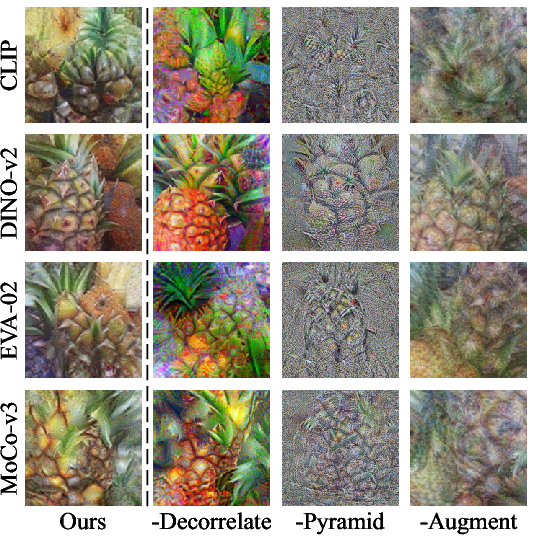

- Helpful add‑ons to make images generalize and look natural:

- Multi‑scale pyramid: Build each synthetic image from blurry to sharp layers (like stacking low‑ to high‑resolution versions) so it doesn’t become weird, high‑frequency noise.

- Differentiable augmentations: Keep flipping, cropping, and noising the synthetic images while optimizing them, in a way the computer can still learn through. This forces the synthetic images to be robust, not fragile.

- Color decorrelation: Adjust colors in a way that reduces odd color artifacts and prevents overfitting to a model’s color quirks.

In short: the system keeps changing the synthetic pictures until, feature‑wise, they push a simple classifier to learn the same boundaries as real data would.

What they found (the key results)

Here are the main takeaways, explained simply:

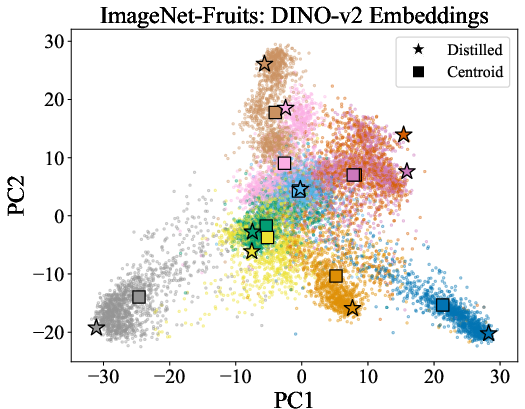

- One image per class can go far: Using just one synthetic image per class, a linear probe trained on top of big pre‑trained models (like DINO‑v2, CLIP, EVA‑02, MoCo‑v3) gets strong test accuracy—much better than using one real image per class chosen by smart rules (like nearest neighbors or class centroids).

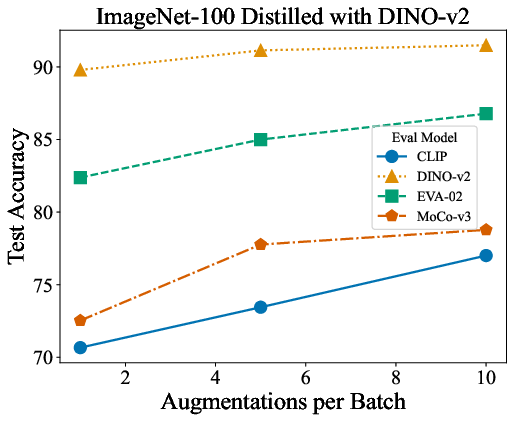

- Works across different models: Synthetic images made using one model (say, DINO‑v2) can still teach a classifier on a different model (like CLIP). Not perfect, but surprisingly good—especially when using the pyramid and augmentations.

- Different models, different “styles”: The distilled images carry the “style” of the model used to make them (some emphasize structure, others texture or color), which gives clues about what each model pays attention to.

- Great for fine‑grained tasks: On datasets where classes are very similar (dog breeds, bird species), the distilled images help even more than on standard datasets. It’s like each synthetic image packs the most important details needed to tell look‑alike classes apart.

- Reveals model biases on tricky datasets: On “spurious correlation” datasets (where, for example, certain dog breeds always appear with certain backgrounds in training but not in testing), the synthetic images expose what a model is relying on. For example, one model’s distilled images showed mostly backgrounds instead of dogs—hinting that it overfits to backgrounds and will fail when backgrounds change.

- Predicts model alignment: How well synthetic images transfer from one model to another lines up with how similar those models’ internal “feature spaces” are. This supports the idea that many modern models learn related representations, even if they’re trained differently.

Why this matters: It shows we can “compress” a dataset into tiny, high‑teaching‑power images for fast training and for peeking into what models actually learn.

Why this matters (the impact)

- Faster, cheaper training: Instead of needing millions of images, you can train a simple classifier with a handful of synthetic ones, saving time and compute.

- Better understanding of models: The look and content of the distilled images help reveal model strengths, weaknesses, and biases (like over‑reliance on backgrounds).

- Useful across models: Because the synthetic images often transfer well, you can make them once and reuse them on different systems.

- Strong on hard tasks: For fine‑grained problems where tiny details matter, these distilled images capture the key differences, helping classifiers perform better with less data.

In short, this work shows a practical way to make tiny, powerful “paper guides” for computer vision models—and to use those guides to understand how different models think.

Knowledge Gaps

Unresolved Knowledge Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

Below is a concise list of specific gaps and open questions the paper leaves unresolved. Each item is framed to be actionable for future research.

- Scope beyond linear probes: The method is only validated for training linear classifiers atop frozen pre-trained backbones; it is unknown how dataset distillation via Linear Gradient Matching (LGM) performs when fine-tuning the backbone, training nonlinear heads (e.g., MLPs), or supporting other learning paradigms (e.g., multi-task, multi-label, or regression).

- Alignment objective design: The meta-loss matches gradient directions (cosine distance) w.r.t. a random linear probe but ignores gradient magnitudes and higher-order dynamics; it is unclear whether incorporating magnitude, second-order (Hessian) information, or trajectory-level alignment improves distillation or cross-model transfer.

- Random probe sampling: The distillation step samples W ~ N(0,1); the impact of W’s distribution, dimensionality, and sampling strategy (e.g., fixed vs. resampled per step, structured initializations, ensembles of probes) on stability, convergence, and transfer is not assessed.

- Loss functions and training protocols: Only multiclass cross-entropy is considered; the effect of alternative objectives (e.g., margin-based losses, label smoothing, focal loss, contrastive losses) and regularizations (e.g., L2/L1 on W, early stopping) on distilled data utility is unexplored.

- Layer choice and feature aggregation: Evaluation uses only the last-layer features of each backbone; whether multi-layer feature fusion, intermediate layers, or learned adapters yield better distilled datasets (especially for cross-model transfer) remains untested.

- Scaling with images-per-class (IPC): The method primarily targets one image per class; the scaling behavior for IPC > 1 (e.g., diversity gains, diminishing returns, optimal IPC per dataset/model) and strategies to capture intra-class variability are not studied.

- Class imbalance and long-tailed distributions: The approach presumes balanced classes; robustness and adaptation for long-tailed or imbalanced datasets (e.g., per-class weighting in gradient matching or label-aware sampling) are not addressed.

- Augmentation design space: Augmentations are limited (flip, random crop, Gaussian noise); the effect of stronger or more varied differentiable augmentations (e.g., color jitter, blur, randaugment, cutout/mixup/cutmix) and the optimal number of “augmentations per batch” across datasets/models is underexplored.

- Pyramid representation schedule: While the pyramid representation improves realism and transfer, the optimal progressive schedule (tier addition timing, resolutions, weights) and its interaction with backbone architecture, resolution, and dataset are not systematically evaluated.

- Cross-model generalization mechanics: Cross-model transfer is variable (e.g., CLIP ↔ MoCo outlier); a rigorous analysis of which representational properties (e.g., invariances, texture/shape bias) drive transferability of distilled datasets and how to optimize for it is missing.

- Formal link to model alignment: The paper suggests distilled cross-model performance correlates with embedding alignment (Platonic representation hypothesis), but provides no comprehensive, large-scale, or statistically rigorous validation across diverse backbones, datasets, and alignment metrics (e.g., mutual kNN sensitivity to k, sampling, and layer choice).

- Comparison to modern distillation baselines: The evaluation omits direct comparisons to recent dataset distillation methods tailored for large models or few-shot settings (e.g., Trajectory Matching variants, Squeeze, FYI, DATM) in the linear-probe regime due to presumed scaling issues; empirical head-to-head comparisons or hybrid approaches would strengthen claims.

- Compute, memory, and scalability: The paper does not report distillation runtime, memory footprint, or scaling curves (iterations, batch size, augmentations-per-batch) across datasets (ImageNet-1k vs. fine-grained) and backbones; practical deployment constraints and optimization opportunities remain unclear.

- Resolution dependence: All experiments use 224×224; how input resolution and patch size (e.g., ViT-B/16 vs. ViT-B/32, high-res inputs) impact distillation quality, realism, and transfer is not evaluated.

- Backbone diversity: Only ViT-B variants of CLIP/DINO/EVA/MoCo are tested; scaling across model sizes (ViT-L/H), CNNs (e.g., ResNet variants), hybrid architectures, and image encoders trained with different modalities or objectives is an open question.

- Robustness to spurious correlations: On adversarial datasets (Spawrious, Waterbirds), distilled images appear to adopt backbone biases; methods to control, detect, or debias distilled content (e.g., background-invariant objectives, counterfactual augmentation, adversarial regularizers) are not proposed or tested.

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) evaluation: ArtBench is mentioned, but OOD generalization results and systematic evaluation (e.g., benchmark suites, shift types, calibration/uncertainty measures) are absent; whether distilled datasets improve or worsen OOD performance is unknown.

- Privacy and memorization risk: Distilled images look realistic; the risk of training data leakage, membership inference, reconstruction of specific samples, or copyright/privacy concerns is not analyzed.

- Stability and reproducibility: Beyond small ± values, a thorough variance analysis across seeds, datasets, and backbones (including failure modes like catastrophic overfitting or convergence instability) is missing, as are guidelines for hyperparameter sensitivity and robust defaults.

- Hybrid training with real data: Whether mixing distilled images with small real subsets (semi-distilled training) yields better accuracy/robustness than either alone—and how to optimally weight or schedule such mixing—remains untested.

- Task breadth: Only classification is studied; extending LGM to other tasks (retrieval, segmentation, detection, pose estimation) and assessing task-specific objectives and evaluation metrics is an open direction.

- Label noise and weak supervision: The method assumes clean labels; its behavior under label noise, partial labels, weak supervision, or self-labeling (pseudo-labels) is not examined.

- Control over distilled content: There is no mechanism to guide distilled images toward specific attributes (e.g., shape bias over texture, invariances, fairness constraints); learning controllable distillation objectives or priors could improve interpretability and robustness.

- Theoretical guarantees: The paper offers no theory linking classifier-gradient alignment to downstream generalization equivalence (e.g., conditions under which matched gradients imply similar risk minimization on real test data); formal analysis or bounds could deepen understanding and guide objective design.

- Release and evaluation artifacts: While a project page is referenced, details on code/data availability, standardized evaluation pipelines, and benchmarks for fair comparison (including alignment metrics) are not provided; this hinders reproducibility and community uptake.

Glossary

- Adversarial datasets: Datasets designed to stress-test models by introducing misleading or confounding signals so performance depends on robust features rather than spurious ones. Example: "spurious correlations in adversarial datasets."

- Backbone model: A pre-trained network used solely as a feature extractor for downstream tasks. Example: "pre-trained self-supervised backbone models."

- Bilinear upsampling: A differentiable image resizing method that interpolates pixel values using bilinear interpolation. Example: "by bilinearly upsampling each level of the pyramids to the max resolution (256) and adding them together before smoothly clamping the pixel values with a sigmoid function:"

- Bi-level optimization: An optimization setup with nested objectives (e.g., inner training loop and outer meta-objective), often challenging for stability and memory. Example: "instability in the bi-level optimization."

- CLIP: A vision-LLM pre-trained via contrastive learning to align image and text representations. Example: "train a linear CLIP probe".

- Cosine distance: A similarity measure based on the cosine of the angle between two vectors; used to compare gradients or embeddings. Example: "our meta loss is then the cosine distance between them:"

- Cross-entropy loss: A standard classification loss measuring the difference between predicted class probabilities and true labels. Example: "where CE is the multiclass cross-entropy loss:"

- Decorrelated color space: A color representation where channel correlations are reduced, used to mitigate color biases during optimization. Example: "we also learn our distilled images in a decorrelated color space"

- Differentiable augmentations: Data transformations implemented as differentiable operations to improve synthetic data quality during optimization. Example: "applying differentiable augmentations to the synthetic images during the distillation process greatly improves the quality of the distilled data."

- Differentiable Siamese Augmentation: A specific differentiable augmentation framework from prior work used to enhance dataset distillation. Example: "As first noted in the work on Differentiable Siamese Augmentation~\citep{dsa},"

- DINO-v2: A self-supervised vision model trained with contrastive objectives and augmentations; used as a feature extractor. Example: "DINO-v2~\citep{oquab2023dinov2}"

- Embedding space: The high-dimensional feature space produced by a model where inputs are represented as vectors. Example: "how similar two models' embedding spaces are"

- EVA-02: A state-of-the-art self-supervised (and hybrid) vision model used as a backbone. Example: "EVA-02~\citep{fang2024eva}"

- Feature extractor: A pre-trained model component that maps inputs to feature embeddings without task-specific heads. Example: "pre-trained feature extractor"

- Feature visualization: Techniques for visualizing and interpreting features learned by neural networks to understand model behavior. Example: "prior feature visualization work~\citep{olah2017feature}"

- Fine-Grained Visual Classification (FGVC): Classification tasks where classes differ by subtle, detailed visual cues (e.g., bird species, dog breeds). Example: "Fine-Grained Visual Classification (FGVC)"

- Fine-tuning: Adapting a pre-trained model to a specific task by continuing training on task-specific data. Example: "either via fine-tuning or by using these models as feature extraction backbones."

- Foundation models: Large pre-trained models intended to serve as general-purpose feature extractors across many tasks. Example: "features extracted by pre-trained vision foundation models."

- Gaussian noising: Adding Gaussian-distributed noise to images as an augmentation to improve robustness and regularization. Example: "horizontal flipping, random resized cropping, and Gaussian noising"

- Gradient matching: A distillation objective that makes synthetic data induce similar gradients to real data during training. Example: "We find that a gradient matching objective alone leads to images that are overfit to a particular model architecture"

- Linear classifier: A simple model (e.g., softmax layer) that maps feature embeddings to class scores via a learned linear transformation. Example: "gradients in a linear classifier similar to those produced by the real data."

- Linear Gradient Matching: The proposed distillation method that optimizes synthetic images so their induced gradients on a random linear probe match those from real data. Example: "We introduce a method of dataset distillation for this task called Linear Gradient Matching"

- Linear probe: A linear classifier trained on fixed pre-trained features to evaluate the quality of the representation. Example: "train linear probes to convergence on the resulting synthetic images."

- Meta loss: An outer objective used to optimize synthetic data (e.g., the cosine distance between real and synthetic gradients). Example: "Our meta loss () is then defined as the cosine distance between the gradients of these classification losses"

- MoCo-v3: A self-supervised contrastive learning model used as a vision backbone. Example: "MoCo-v3~\citep{mocov3}"

- Model alignment: The degree to which different models’ embedding spaces organize data similarly. Example: "measure the alignment of two models"

- Multi-scale pyramid: A representation that stores images across multiple resolutions to regularize optimization and reduce high-frequency artifacts. Example: "re-parameterization of images via a multi-scale pyramid."

- Mutual k nearest neighbors: A metric for measuring alignment between models by comparing overlap in nearest neighbors across their embedding spaces. Example: "called ``mutual nearest neighbors.''"

- Platonic Representation Hypothesis: The hypothesis that different large models converge to similar representations across modalities. Example: "dubbed this observation the ``Platonic Representation Hypothesis''"

- Principal component analysis (PCA): A dimensionality reduction technique used to visualize and analyze embedding distributions. Example: "the 2D principal component analysis (PCA)."

- Pyramid representation: An image parameterization using multiple resolution levels to improve realism and transferability of distilled images. Example: "we instead adopt a pyramid representation for the distillation process."

- Random resized cropping: An augmentation that randomly crops and resizes images to introduce scale and translation variability. Example: "horizontal flipping, random resized cropping, and Gaussian noising"

- Self-supervised learning: Training models using unlabeled data by designing proxy tasks that yield useful representations. Example: "Self-Supervised Learning has become the defacto method of pre-training neural networks"

- Spurious correlations: Non-causal associations (e.g., backgrounds) that models may exploit, harming generalization. Example: "spurious background correlations"

- Trajectory Matching: A distillation method that matches multi-step training trajectories rather than single-step gradients. Example: "Trajectory Matching~\citep{mtt} and its modifications~\citep{tesla,datm,paszke2017automatic,son2024fyi,glad} still reign supreme."

- Vision-LLMs: Models jointly trained on images and text to align multimodal representations. Example: "vision-LLMs~\citep{clip,siglip,siglip2,EVA-CLIP}"

- Vision Transformer (ViT-B): A transformer-based vision architecture; “B” denotes the base model size. Example: "use the ``ViT-B'' version of the given model."

Practical Applications

Practical Applications of Linear Gradient Matching (Dataset Distillation for Pre-Trained Self-Supervised Vision Models)

Below are actionable, real-world applications derived from the paper’s findings, organized by deployability. Each item notes relevant sectors, potential tools/workflows, and key assumptions or dependencies that affect feasibility.

Immediate Applications

- Model bootstrapping with tiny training sets for linear probes

- Sectors: Software, mobile/edge AI, robotics, retail, manufacturing

- What: Train high-performing linear classifiers using one synthetic image per class instead of large real datasets. Useful for rapid prototypes or on-device updates where storage/compute is constrained.

- Tools/Workflows: “Probe Packs” (distilled per-class images shipped with foundation models); CLI/API to distill per-task images and train a linear head; MLOps recipes for fast retraining on device.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Downstream task must be linearly separable in the chosen backbone’s embedding space; access to a strong pre-trained backbone (e.g., DINO-v2, CLIP); distillation compute is done once per task.

- Rapid backbone selection and benchmarking

- Sectors: Industry R&D, academia

- What: Use the same distilled dataset to quickly evaluate and rank multiple backbones by linear-probe performance, reducing full-dataset training cost/time.

- Tools/Workflows: “Backbone shootout” scripts that train linear heads on multiple models using the same distilled set; automated report generation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Cross-model generalization correlates with model alignment; results reflect linear separability and may not extend to non-linear fine-tuning.

- Interpretability and bias/spurious correlation auditing

- Sectors: Responsible AI, governance/compliance, policy, academia

- What: Distilled images reveal which features a model prioritizes (e.g., backgrounds vs. objects), helping diagnose spurious correlations and model biases (as shown on Spawrious/Waterbirds).

- Tools/Workflows: Bias dashboards that visualize per-class distilled images; “spurious feature detector” that distills on adversarial datasets and flags background-focused artifacts.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Interpretability relies on distilled images reflecting model inductive biases; requires careful human analysis to avoid over-interpretation.

- Privacy-aware data sharing and collaboration

- Sectors: Healthcare, finance, gov/defense, enterprise

- What: Share synthetic distilled images instead of raw data to enable partners to train linear heads without exposing sensitive content.

- Tools/Workflows: Data exchange portals that generate/share per-class distilled exemplars with metadata; contract templates clarifying synthetic data usage.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: While distilled images reduce direct exposure of PII, they can still encode sensitive patterns; perform privacy audits and legal review.

- Fine-grained classification bootstrapping

- Sectors: Retail SKU recognition, biodiversity monitoring, quality control/defect detection

- What: Use distilled images to capture discriminative features for difficult, fine-grained tasks where single real images are insufficient.

- Tools/Workflows: Library of class-specific distilled images as “didactic exemplars” for each SKU/species/defect; rapid deployment of linear probes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Strong backbone for the specific domain; representative class definitions; rare edge cases may be underrepresented.

- Lightweight on-device adaptation for edge/IoT

- Sectors: Smart cameras, drones/robots, wearables

- What: Store and use tiny distilled datasets to update or personalize linear heads locally without transmitting or storing large datasets.

- Tools/Workflows: Embedded training modules that accept distilled sets and retrain linear layers; scheduled retraining jobs on-device.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Local compute must suffice for linear head training; reliable backbone features on-device; stable class ontologies.

- Dataset and label sanity checks

- Sectors: MLOps, data ops, enterprise ML

- What: Use distilled images to spot mislabeled classes, overlapping categories, or class-definition drift by visual inspection of “class prototypes.”

- Tools/Workflows: Data QA dashboards that render distilled-per-class images for curator review; alerts when prototypes exhibit unexpected textures/backgrounds.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Human-in-the-loop review; distilled images may emphasize discriminative but non-semantic cues if backbone is biased.

- Regression tests and CI for training pipelines

- Sectors: Software/MLOps

- What: Maintain a small, fixed distilled set per task as a fast regression test to catch training pipeline regressions.

- Tools/Workflows: CI tasks that train a linear head on the distilled set and compare accuracy/gradients to baselines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Distilled set remains valid as backbone and data distribution stay stable; refresh needed after major model/data changes.

- Cross-model alignment probing

- Sectors: Research, model governance, vendor selection

- What: Use cross-model performance of distilled datasets to estimate alignment between model embedding spaces (a practical proxy for the “Platonic Representation” hypothesis).

- Tools/Workflows: “Alignment probe kit” that distills once and evaluates across candidate backbones to guide model choice.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Observed correlation between cross-model distilled performance and embedding-space alignment holds best for similar architectures/domains.

- Cost- and carbon-efficient experimentation

- Sectors: Startups, academia, enterprise R&D

- What: Replace large-scale runs with distilled-set experiments for fast iteration and lower energy costs.

- Tools/Workflows: Low-cost experimentation pipelines; budget/capacity planners optimized for distilled-set cycles.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Findings extrapolate to full-data performance for linear probes; not a substitute for final full-data validation in critical deployments.

Long-Term Applications

- Beyond linear probes: distilled sets for non-linear fine-tuning, detection, and segmentation

- Sectors: Autonomous systems, healthcare imaging, robotics, media

- What: Extend gradient-matching distillation to non-linear heads and other tasks (segmentation/detection), enabling small synthetic datasets to support broader fine-tuning.

- Tools/Workflows: Task-aware distillation objectives; pyramid/augmentation extensions; task-specific evaluators.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Requires research to stabilize bi-level optimization and avoid overfitting; higher memory/compute demands.

- Federated learning with distilled communication

- Sectors: Mobile, healthcare, finance

- What: Clients send tiny distilled datasets instead of gradients/weights to reduce bandwidth and improve privacy in federated settings.

- Tools/Workflows: Client-side distillers; server-side aggregation of synthetic exemplars; privacy-preserving audits.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Need proofs/guarantees against leakage via synthetic data; robust aggregation across heterogeneous clients and distributions.

- Continual learning and memory replay

- Sectors: Robotics, edge AI, defense

- What: Use per-task distilled exemplars as “compressed memory” to mitigate catastrophic forgetting during continual updates.

- Tools/Workflows: Memory banks of distilled exemplars; replay scheduling; task-change detectors.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Must preserve old-task performance without inflating memory; verify robustness across long task sequences.

- Regulatory audit artifacts and standards

- Sectors: Policy, compliance, public sector, high-stakes industries

- What: Standardize distilled exemplars as audit artifacts to inspect feature focus, bias, and alignment across models used in regulated contexts.

- Tools/Workflows: Auditable “distilled model cards” with per-class images and metrics; certification checklists referencing distilled probes.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Requires consensus on interpretability value and procedures; legal frameworks recognizing synthetic audit artifacts.

- Data licensing and IP-compliant model training

- Sectors: Media, enterprise, gov

- What: Replace or supplement licensed datasets with distilled proxies that preserve task-relevant signals while complying with usage restrictions.

- Tools/Workflows: Distillation under compliant licenses; legal review pipelines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Unsettled IP status of synthetic data derived from licensed sources; quality for rare/nuanced classes may suffer.

- Automated model selection and task-to-backbone routing

- Sectors: AutoML, platform ML, cloud AI

- What: AutoML systems distill task datasets and select the best backbone based on cross-model distilled performance, then deploy the chosen pairing.

- Tools/Workflows: Automated distill-evaluate-select loops; dashboards comparing alignment and performance.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Robustness of distilled performance as a predictor of final task performance; need to handle domain shifts.

- Domain-specific compressed pretraining kits

- Sectors: Medical imaging, geospatial, industrial inspection

- What: Provide small, curated distilled sets per domain paired with a recommended backbone for rapid capability transfer within organizations.

- Tools/Workflows: Domain “starter packs” with distilled images, training scripts, and governance docs.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Requires strong domain backbones; careful validation of clinical/operational safety; address rare-condition underrepresentation.

- Hardware-aligned distillation and training accelerators

- Sectors: Semiconductors, edge AI

- What: Hardware/firmware that accelerates pyramid-based image parameterization and gradient matching, enabling near-real-time on-device distillation.

- Tools/Workflows: Distillation kernels; optimized augmentation engines.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Market demand for on-device distillation; standardization of distillation objectives.

Key Cross-Cutting Assumptions and Dependencies

- The downstream classifier is a linear probe on top of a high-quality pre-trained backbone (e.g., DINO-v2, CLIP). Non-linear fine-tuning is out of scope for the current method.

- Class definitions remain stable; one image per class works best when classes are linearly separable in the chosen embedding.

- Cross-model transfer depends on model alignment; some pairs (e.g., CLIP ↔ MoCo-v3 in the paper) may perform poorly.

- Distillation must include regularization (pyramid parameterization, color decorrelation) and differentiable augmentations to avoid overfitting and adversarial patterns.

- Synthetic images can reflect and even amplify backbone biases and spurious correlations. Auditing is essential for high-stakes use cases.

- Privacy/IP: While synthetic, distilled images may still encode sensitive or proprietary patterns. Employ privacy assessments and legal review before sharing.

- Final deployment in critical domains should validate with full or augmented real datasets; distilled sets are best for bootstrapping, rapid iteration, and interpretability rather than full replacement in safety-critical settings.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.