Diffusion As Self-Distillation: End-to-End Latent Diffusion In One Model

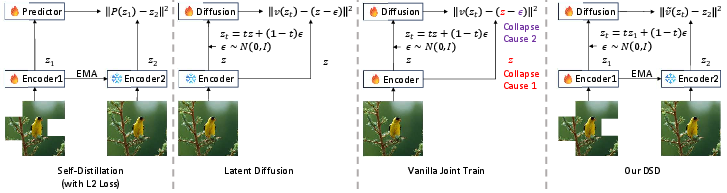

Abstract: Standard Latent Diffusion Models rely on a complex, three-part architecture consisting of a separate encoder, decoder, and diffusion network, which are trained in multiple stages. This modular design is computationally inefficient, leads to suboptimal performance, and prevents the unification of diffusion with the single-network architectures common in vision foundation models. Our goal is to unify these three components into a single, end-to-end trainable network. We first demonstrate that a naive joint training approach fails catastrophically due to ``latent collapse'', where the diffusion training objective interferes with the network's ability to learn a good latent representation. We identify the root causes of this instability by drawing a novel analogy between diffusion and self-distillation based unsupervised learning method. Based on this insight, we propose Diffusion as Self-Distillation (DSD), a new framework with key modifications to the training objective that stabilize the latent space. This approach enables, for the first time, the stable end-to-end training of a single network that simultaneously learns to encode, decode, and perform diffusion. DSD achieves outstanding performance on the ImageNet $256\times 256$ conditional generation task: FID=13.44/6.38/4.25 with only 42M/118M/205M parameters and 50 training epochs on ImageNet, without using classifier-free-guidance.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about

This paper is about making image generation models simpler and better. Today’s popular diffusion models often use three separate parts: an encoder (to turn an image into a compact code), a decoder (to turn the code back into an image), and a diffusion network (to add and remove noise so it can generate new images). Training these three parts separately is slow, complicated, and not always ideal. The authors show how to combine all three into a single model that can be trained end-to-end, and they explain how to fix a big training problem that appears when you try to do this directly.

The big questions the paper asks

- Can we build one unified model that learns to encode images, decode them, and do diffusion, all at the same time?

- Why does “naive” end-to-end training break down (the model’s internal codes collapse and become useless)?

- Is there a better way to design the training objective so the model learns stable, high-quality internal codes and generates good images?

How the model works and what ideas it uses

First, a quick tour of key terms

- Encoder/decoder: Think of the encoder as a “compressor” that turns an image into a short code (called a latent). The decoder is the “decompressor” that turns the code back into a full image.

- Diffusion model: Imagine starting with random noise and then gradually “denoising” it to get a realistic image. The diffusion model learns how to remove noise step by step.

- Latent space: This is the space of those short codes. A good latent space keeps important information while staying compact.

- Collapse: If training goes wrong, all codes become very similar (like everyone handing in the same summary for different books). Then the decoder can’t reconstruct different images well.

Why naive joint training fails

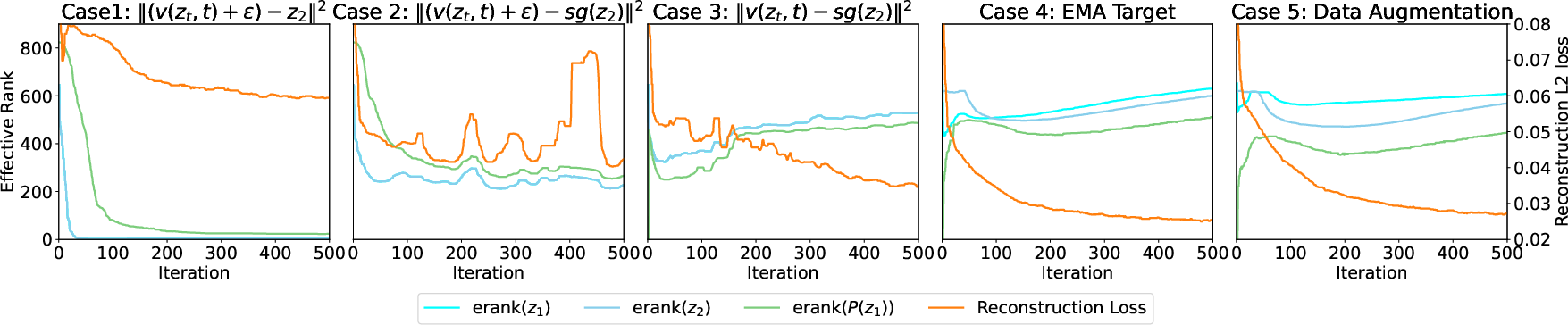

If you just train everything together with the standard diffusion loss, two bad things happen:

- Latent variance suppression: The standard loss quietly pushes the encoder to make all codes more similar (low variance). That means the latent space loses variety and “collapses,” so reconstructions get worse.

- Rank differentiation failure: Stable self-supervised learning (like self-distillation methods) works when the predictor is a kind of “smoother” that simplifies its input features. But the usual diffusion objective makes the predictor output a high-detail, high-rank signal (due to the added random noise), which breaks that stability trick and encourages collapse.

The core idea: treat diffusion like self-distillation

Self-distillation is a popular way to learn without labels: a “student” network learns to match a “teacher” network’s representations. The teacher changes slowly (using EMA, a method that averages past teacher versions), which keeps training stable.

The authors re-interpret diffusion training as a kind of self-distillation and make two key fixes:

- Decoupling with stop-gradient: They stop gradients from flowing into the target latent. In simple terms, they let the predictor learn to match the target, but they don’t let the loss squeeze the encoder’s latent space directly. This protects the variety (variance) of the latents.

- Loss transformation to predict clean latents: Instead of predicting “velocity” (a noisy, high-rank signal tied to the difference between clean data and noise), they train the model to predict the clean latent directly from a noisy latent. Predicting the clean latent is a denoising task that naturally acts like a low-pass filter (a smoother), which restores the stability mechanism seen in self-distillation.

The unified architecture

They build one Vision Transformer (ViT) backbone with multiple small heads:

- An image head for encoding and decoding (so it’s a full autoencoder).

- A “clean latent” prediction head for the self-distillation-style denoising loss.

- A “velocity” head used for final sampling (kept detached so it doesn’t hurt the stable training).

They also use:

- A teacher encoder updated via EMA to provide stable targets.

- Strong data augmentation (like masking and blurring) to force the predictor to truly denoise and smooth.

- A few helper losses (like feature alignment and a simple classification head) to improve the learned representations.

What they found and why it matters

- Stable end-to-end training in one model: For the first time, they train a single network that learns to encode, decode, and perform diffusion—all together—without the latent space collapsing.

- Strong image generation results with fewer parameters: On ImageNet at 256×256 resolution, their largest model (about 205M parameters) achieves an FID of 4.25, which is competitive with or better than some models that use many more parameters (often 700M+ when counting separate encoder/decoder). They also report good performance for smaller models (42M and 118M parameters), trained for only 50 epochs.

- No classifier-free guidance needed: They get strong results even without a commonly used trick called classifier-free guidance, which usually boosts image quality but adds complexity.

- Efficient and scalable: As the model size grows, performance improves in a predictable way. Because they don’t need separate, large components, training and inference can be simpler and faster overall.

What this could mean going forward

- Simpler generative systems: This approach could make high-quality image generators easier to build, train, and deploy, by avoiding separate encoders/decoders and long multi-stage training.

- Unification with foundation models: Many modern vision “foundation models” use a single network for many tasks. This paper’s method brings diffusion closer to that style, potentially making it a better candidate for standard pretraining and multi-task use.

- Better, more stable training: By connecting diffusion to self-distillation and fixing the collapse problem, future models could be more robust, learn better representations, and require fewer parameters to match or beat existing benchmarks.

In short, the paper shows how to turn diffusion training into a stable, self-distillation-like process, allowing one unified model to do encoding, decoding, and generation effectively. This makes powerful image generation more accessible and efficient, and it opens the door to simpler, unified AI systems.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

The following list captures what remains missing, uncertain, or unexplored in the paper, with concrete items future researchers could act on:

- External validity across datasets and resolutions:

- Evaluate DSD on diverse datasets beyond ImageNet (e.g., COCO, FFHQ, LSUN, LAION) and at higher resolutions (512×512, 1024×1024) to test stability and image quality under distributional and scale shifts.

- Conditioning modalities and tasks:

- Extend and assess DSD under text conditioning (text-to-image), unconditional generation, and multi-modal settings (e.g., audio, video), and quantify whether the collapse-avoidance strategies transfer intact.

- Reconstruction quality and tokenizer comparison:

- Report autoencoding metrics (e.g., rFID, PSNR, LPIPS) and compare the unified decoder against strong tokenizers/VAEs (e.g., VQGAN, RAE, LightningDiT tokenizers) under matched settings.

- Fairness and rigor in comparisons:

- Provide apples-to-apples evaluations with matched training budgets, data, samplers, and epochs; control for differences like use of OpenImages in baselines and significantly longer training schedules.

- Classifier-free guidance (CFG) clarity:

- Resolve inconsistencies between claims (“without CFG”) and usage (figure shows CFG scale 7.3; table reports w/ and w/o CFG). Quantify DSD’s dependency on CFG and report guidance sensitivity curves.

- Efficiency claims:

- Measure and report training and inference efficiency (wall-clock sampling speed, throughput, memory footprint, latency) versus modular LDMs and autoregressive baselines, not just parameter counts.

- Theoretical guarantees and scope:

- Formalize conditions under which stop-gradient removes variance suppression without undermining learning signals to the encoder, and provide convergence/stability guarantees for the transformed clean-latent objective.

- Loss transformation correctness:

- Analyze the impact of removing the time weight (introduced by the algebraic equivalence) on optimality and sampling correctness; quantify bias introduced by the unweighted clean-latent objective and its effect on the learned generative distribution.

- Detached velocity head design:

- Clarify the training target for the velocity head (which “z” is used, and how it relates to the EMA target), and ablate its necessity, stability near , and sampling quality versus directly computing velocity from the clean-latent predictor.

- Rank differentiation mechanism validity:

- Move beyond intuitive arguments and empirically validate rank differentiation across layers and settings; establish quantitative criteria for “low-pass behavior” of the predictor and its dependence on augmentation strength, architecture depth, and latent dimension.

- Sensitivity to hyperparameters:

- Systematically ablate EMA rate, augmentation types/strength (e.g., mask ratio), time-step distribution , noise schedule, loss weights among DSD/rec/velocity/aux losses, gradient clipping, and optimizer choice (Muon vs AdamW).

- Latent space design:

- Explore scaling laws for latent tokens (count) and dimensions (e.g., d=16 vs larger), and characterize failure regions where collapse reappears or quality degrades; test whether higher-dimensional latents improve fidelity without destabilizing training.

- Role of supervised signals:

- Quantify how much the classification head (with labels) contributes to generative quality and latent stability; rerun purely unsupervised training to validate DSD’s claimed alignment with unsupervised/self-distillation paradigms (linear probe, retrieval, segmentation downstream).

- Multi-objective interference:

- Investigate interactions among reconstruction, clean-latent prediction, velocity, and auxiliary alignment losses; provide schedules/weighting strategies to avoid negative transfer and show ablations isolating each component’s contribution.

- Decoder (GAN) specification and reproducibility:

- Detail the GAN architecture (discriminator design, training schedule, regularization), noise interpolation implementation, and exact loss coefficients; release code to ensure reproducibility.

- Effective rank measurement:

- Complement effective rank with additional collapse diagnostics (e.g., covariance spectra over training, mutual information estimates, batch-size effects) and analyze internal transformer layer representations, not just final latents.

- Sampler and step sensitivity:

- Evaluate different samplers (DDIM, Heun, DPM-Solver) and step counts; provide quality–compute tradeoff curves for DSD versus modular LDMs.

- Robustness and diversity:

- Test robustness to distribution shift, corruptions, and augmentations at inference; measure diversity metrics (precision/recall, coverage) to ensure the low-pass behavior doesn’t over-smooth or reduce sample diversity.

- Transferability to vision foundation tasks:

- Substantiate the “unification” claim by evaluating DSD-pretrained backbones on standard downstream tasks (classification, detection, segmentation) versus DINO/MAE/JEPA baselines.

- Formal derivation completeness:

- Include full proofs/derivations for the variance decomposition of the diffusion loss and the equivalence to clean-latent prediction under practical training modifications (stop-gradient, EMA, removal of ), ensuring the theory matches the implemented objectives.

Glossary

- Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG): A technique that improves conditional diffusion sampling by interpolating conditional and unconditional scores without using a separate classifier. "We use a classifier-free guidance scale $7.3$."

- Detached Velocity Loss: A training objective for the diffusion head where gradients to the target velocity are stopped to avoid corrupting backbone features. "A separate head is trained for the final sampling process."

- DiT (Diffusion Transformer): A transformer-based architecture tailored for diffusion modeling. "specifically utilizing the velocity prediction objective, consistent with modern architectures like DiT~\citep{dit} and LightningDiT~\citep{VAVAE}."

- DSD (Diffusion as Self-Distillation): A unified framework that stabilizes and trains encoder, decoder, and diffusion in one network by viewing diffusion as self-distillation. "we propose Diffusion as Self-Distillation (DSD), a new framework with key modifications to the training objective that stabilize the latent space."

- Effective Rank (erank): A smooth measure of a representation’s effective dimensionality based on entropy of singular values. "We analyze dimensional collapse using the Effective Rank (~\citep{erank}), which provides a smooth, continuous measure of the dimensionality of a representation matrix."

- EMA (Exponential Moving Average): A parameter update scheme that maintains a smoothed target encoder for stable training. "which is a frozen copy updated via Exponential Moving Average (EMA)."

- Euler sampler: A numerical sampler used for generation in diffusion models using Euler integration steps. "For sampling, we use the Euler sampler with 250 steps, following the LightningDiT approach~\citep{VAVAE}."

- Fréchet Inception Distance (FID): A standard metric for generative image quality comparing feature distributions. "We report the following standard metrics, measured on 50K generated images: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID)~\cite{fid}, Structural FID (sFID)~\cite{sfid}, Inception Score (IS)~\cite{is}."

- I-JEPA: A self-supervised joint-embedding predictive architecture for representation learning. "Self-Distillation (SD) has become a dominant paradigm in unsupervised representation learning, with major models including DINO~\citep{dino}, DiNOv2~\citep{dinov2}, DiNOv3~\citep{dinov3}, BYOL~\citep{BYOL}, and I-JEPA~\citep{JEPA}."

- Inception Score (IS): A metric assessing the diversity and quality of generated images via the Inception network’s outputs. "We report the following standard metrics, measured on 50K generated images: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID)~\cite{fid}, Structural FID (sFID)~\cite{sfid}, Inception Score (IS)~\cite{is}."

- Latent Collapse: A failure mode where the latent space’s effective dimensionality collapses, harming reconstruction and generation. "latent collapse'', where the diffusion training objective interferes with the network's ability to learn a good latent representation."

- Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs): Diffusion models operating in a compact learned latent space produced by a VAE. "The breakthrough of Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs)~\citep{ldm,emu,sd3,flux} shifted the focus to a more compact, learned latent space provided by a pretrained Variational AutoEncoder (VAE~\citep{vae})."

- Latent Score-Based Generative Models (LSGM): Score-based generative modeling conducted in latent space to improve efficiency and stability. "Latent Score-Based Generative Models (LSGM)~\citep{LSGM} explored joint optimization by an explicit entropy regularization term on the latent space to maintain latent variance and avoid collapse."

- Latent Variance Suppression: An implicit effect in the diffusion loss that pushes the encoder to minimize latent variance, leading to collapse. "Root Cause 1: Latent Variance Suppression. The L2 loss term implicitly contains a term proportional to the variance of the latent representation."

- LightningDiT: A diffusion transformer variant/framework used as a modern baseline. "specifically utilizing the velocity prediction objective, consistent with modern architectures like DiT~\citep{dit} and LightningDiT~\citep{VAVAE}."

- Muon optimizer: An optimizer used for training large-scale models with settings suited for stability and efficiency. "For optimization, we use the Muon optimizer~\citep{muon, KimiMuon}, with a weight decay of and a base learning rate of ."

- Noise interpolation: Injecting noise into latents during reconstruction to regularize the latent space and share computation. "We introduce noise interpolation into , following \citet{detok}, which is fed to the decoder head for reconstruction:"

- Rank Differentiation Mechanism: A stability mechanism in self-distillation requiring the predictor to output lower-rank features than the target. "The stability of these methods can be explained by the rank differentiation mechanism~\citep{RankDiff}."

- REPA: A representation autoencoder approach used for alignment and reconstruction within latent diffusion frameworks. "Following REPA~\citep{repa}, we use cosine similarity to align the representations from the first few ViT layers (e.g., layers 0 and 1) to features from a strong teacher model like DINOv3~\citep{dinov3}."

- REPA-E: A representation-efficient partial autoencoder design enabling end-to-end tuning alongside diffusion. "Representation-Efficient Partial Autoencoders (REPA-E)~\citep{REPA-E} proposed replacing the traditional VAE with a partial autoencoder that uses the diffusion U-Net's intermediate features for reconstruction."

- Self-Distillation (SD): An unsupervised learning paradigm where an online network learns to match a target network’s representations. "Self-Distillation (SD) has become a dominant paradigm in unsupervised representation learning, with major models including DINO~\citep{dino}, DiNOv2~\citep{dinov2}, DiNOv3~\citep{dinov3}, BYOL~\citep{BYOL}, and I-JEPA~\citep{JEPA}."

- sFID (Structural FID): A generation quality metric emphasizing structural fidelity. "We report the following standard metrics, measured on 50K generated images: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID)~\cite{fid}, Structural FID (sFID)~\cite{sfid}, Inception Score (IS)~\cite{is}."

- Stop-gradient (sg) operator: An operation that prevents backpropagation through a tensor to decouple objectives. "We use the stop-gradient () operator on the target clean latent to eliminate the gradient path that penalizes latent variance..."

- Velocity prediction objective: A diffusion training objective where the model predicts the velocity from noise to the clean latent. "specifically utilizing the velocity prediction objective, consistent with modern architectures like DiT~\citep{dit} and LightningDiT~\citep{VAVAE}."

- Vision Transformer (ViT): A transformer architecture processing images as token sequences used as the unified backbone. "Our predictor is a Vision Transformer (ViT~\citep{ViT}) that takes a noisy version of as input:"

- VAE (Variational AutoEncoder): A generative autoencoder that learns a latent distribution enabling reconstruction and sampling. "provided by a pretrained Variational AutoEncoder (VAE~\citep{vae})."

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The paper’s unified Diffusion as Self-Distillation (DSD) approach enables a number of deployments that can be adopted with existing engineering capacity, especially in ImageNet-like, class-conditional, 256×256 image generation settings.

- Streamlined production pipelines for generative imaging (software, creative tech)

- Use case: Replace the 3-component Latent Diffusion Model (VAE encoder + decoder + diffusion) with a single ViT backbone and task-specific heads to cut engineering complexity, parameter overhead, and latency.

- Tools/workflows: “DSD-based image generator” SDK; training recipe with EMA target encoder, aggressive augmentations, and clean-latent prediction loss; effective-rank monitoring during training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Demonstrated on ImageNet at 256×256; conditional setup; requires PyTorch stack, EMA update, and augmentation strategy; scaling beyond shown sizes may need additional tuning.

- On-device or edge image generation for consumer apps (software, mobile; daily life)

- Use case: Deploy DSD-S (≈42M params) for offline image editing, stylization, and lightweight generation in mobile apps without classifier-free guidance.

- Tools/workflows: Quantization and distillation pipelines; hardware-specific kernels; Euler sampler with limited steps.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Performance is reported for 256×256; device RAM/compute constraints; mobile optimizations (e.g., int8) required; quality vs. latency trade-offs.

- Cost and energy reductions in inference/training (industry, sustainability policy)

- Use case: Lower compute and memory by removing separate VAE modules (encoder/decoder often ~20% parameters in LDMs) and cutting data-transfer overhead between modules.

- Tools/workflows: Consolidated model deployment; profiling utilities to track parameter- and FLOP-reductions; internal sustainability reporting dashboards.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Realized savings depend on model size, batch scheduling, and infrastructure; quantifiable carbon savings require standardized measurement.

- Faster prototyping of generative models (academia, startups; software)

- Use case: Achieve competitive FID with fewer epochs (e.g., DSD-B: FID 4.25 after 50 epochs) to iterate rapidly on new datasets or tasks.

- Tools/workflows: Muon optimizer, effective-rank diagnostics, combined reconstruction + self-distillation training.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires careful augmentation (masking, color jitter) and EMA target encoder; performance verified for ImageNet-like conditional settings.

- Synthetic data generation for downstream model training (academia, industry; vision)

- Use case: Class-conditional augmentation of datasets for classification, detection, or segmentation when real data is scarce or imbalanced.

- Tools/workflows: DSD sampling integrated with data pipelines; selection/filtering via CLIP-like scoring or human-in-the-loop.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Distribution shifts and label fidelity must be validated; synthetic data may bias models if not curated; suitability depends on downstream task.

- Unified representation + generation pretraining for vision models (academia; foundation models)

- Use case: Train a single backbone to learn robust latents via self-distillation while remaining generative via a diffusion head, reducing fragmentation between pretrain tasks (e.g., MAE/JEPA) and generative objectives.

- Tools/workflows: Multi-head ViT backbone; auxiliary alignment with DINOv3 features; intermediate-layer SD losses.

- Assumptions/dependencies: External teacher (e.g., DINOv3) used for alignment; generalization to non-ImageNet domains requires revalidation.

- Training stability monitors using effective-rank (academia, MLOps)

- Use case: Add “effective rank” metrics in training dashboards to detect and prevent latent collapse early in runs.

- Tools/workflows: Batch-wise SVD/effective-rank computations; alerting thresholds; automated mitigation (e.g., stop-gradient on targets).

- Assumptions/dependencies: Overhead of rank calculation must be managed; thresholds are task-dependent.

- Marketing/commerce content generation at 256×256 (industry; media/ads)

- Use case: Rapid generation of product shots, backgrounds, and concept visuals without classifier-free guidance.

- Tools/workflows: Promptable conditional interface; content safety filters; A/B testing of style presets.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Resolution constraints; brand/IP compliance; human review in the loop for quality and safety.

Long-Term Applications

The DSD framework suggests broader, scalable applications once extended to new modalities, resolutions, and domains, and after further research on safety, robustness, and regulation.

- Multimodal unified foundation models (software, foundation models)

- Use case: Extend DSD to text, audio, and video conditioning (e.g., “any-to-any” generation) in a single backbone, simplifying large-model ecosystems.

- Tools/workflows: Shared ViT backbone with multimodal heads; tokenizer-free or learned latent bridge across modalities.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires large-scale multimodal datasets, robust conditioning (text encoders), and careful scaling laws.

- Medical imaging denoising and reconstruction (healthcare)

- Use case: Single-network MRI/CT reconstruction and generative denoising in compact latents, potentially enabling faster acquisition or better image quality.

- Tools/workflows: Domain-specific augmentation, physics-informed conditioning, clinical validation pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Regulatory approval; rigorous validation; high-resolution training; handling domain shift and patient safety.

- Robotics world models and planning (robotics)

- Use case: Learn compact generative latents for model-based planning, simulated rollouts, and environment synthesis on edge hardware.

- Tools/workflows: Temporal extensions of DSD; integration with control policies; sim-to-real adaptation.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stability of temporal diffusion; safety-critical evaluation; robust generalization.

- Video generation/editing in a unified backbone (media, creative)

- Use case: Replace separate video tokenizers and diffusion models with one DSD-style ViT, enabling end-to-end video synthesis and editing.

- Tools/workflows: Spatiotemporal latent design; temporal augmentations; scalable storage/streaming.

- Assumptions/dependencies: High compute; large video datasets; temporal coherence constraints.

- 3D asset creation and neural rendering (graphics, gaming)

- Use case: Extend DSD to geometry-aware latents (camera models, NERF-like features) for 3D content generation.

- Tools/workflows: Multi-view conditioning; differentiable rendering heads; CAD/engine pipelines.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Geometry supervision; dataset curation; performance at high resolutions.

- Energy-aware AI policy and reporting (policy, sustainability)

- Use case: Encourage single-backbone generative models to reduce energy footprints; standardize compute/carbon reporting across model life cycles.

- Tools/workflows: Auditable logs of FLOPs, training hours, and energy; green model registries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Sector-wide adoption; measurement standards; incentives or regulation.

- Privacy-preserving, on-device generative personalization (daily life, privacy tech)

- Use case: Personalized style transfer, avatars, and filters trained/fine-tuned locally using unified DSD backbones.

- Tools/workflows: Federated fine-tuning; secure model update channels; local safety filters.

- Assumptions/dependencies: On-device memory/compute; privacy guarantees; content moderation.

- Safer generative systems via rank-aware training (academia, governance)

- Use case: Use the rank-differentiation mechanism and clean-latent objective to build more stable and interpretable generative training procedures.

- Tools/workflows: Rank metrics, stop-gradient targets, projector design audits.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Requires empirical links to reduced harmful failure modes; not yet established for content safety.

- Education and simulation content generation (education)

- Use case: Generate visual simulations, lab diagrams, and practice imagery with lower compute budgets in schools or low-resource settings.

- Tools/workflows: Curriculum-aligned generators; teacher dashboards; QA rubrics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Cultural and factual alignment; accessibility and device constraints.

- Platform tools and libraries (software ecosystem)

- Use case: Commercial/open-source toolkits implementing DSD training/inference: “UnifiedViT GenKit”, “DSD Trainer”, rank-diagnostics plugins.

- Tools/workflows: Modular codebases; MLOps integrations; model cards tailored for unified backbones.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Community adoption; benchmarks beyond ImageNet; compatibility with popular inference engines.

- Content authenticity and watermarking research (policy, media integrity)

- Use case: Leverage consistent latent spaces and reduced reliance on guidance to embed or detect provenance signals.

- Tools/workflows: Watermarking in latent space; authenticity validators; policy-aligned disclosure mechanisms.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Technical robustness of watermarking; ecosystem acceptance; regulatory frameworks.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Proven scope: 256×256 conditional image generation on ImageNet, with strong FID and parameter efficiency; no text conditioning demonstrated.

- Core dependencies: EMA target encoder, aggressive augmentations, clean-latent prediction loss, detached velocity head for sampling stability.

- Scaling gaps: High-resolution, multimodal, and safety-critical domains need further research, compute, and domain-specific validation.

- Governance: Any deployment that touches sensitive content or people requires safety layers, dataset audits, and compliance with local regulations.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.