- The paper demonstrates that a contrastive InfoNCE-style loss can match METRA performance, simplifying representation learning in unsupervised skill discovery.

- It introduces the CSF algorithm, which leverages successor features to learn policies with fewer hyperparameters compared to METRA.

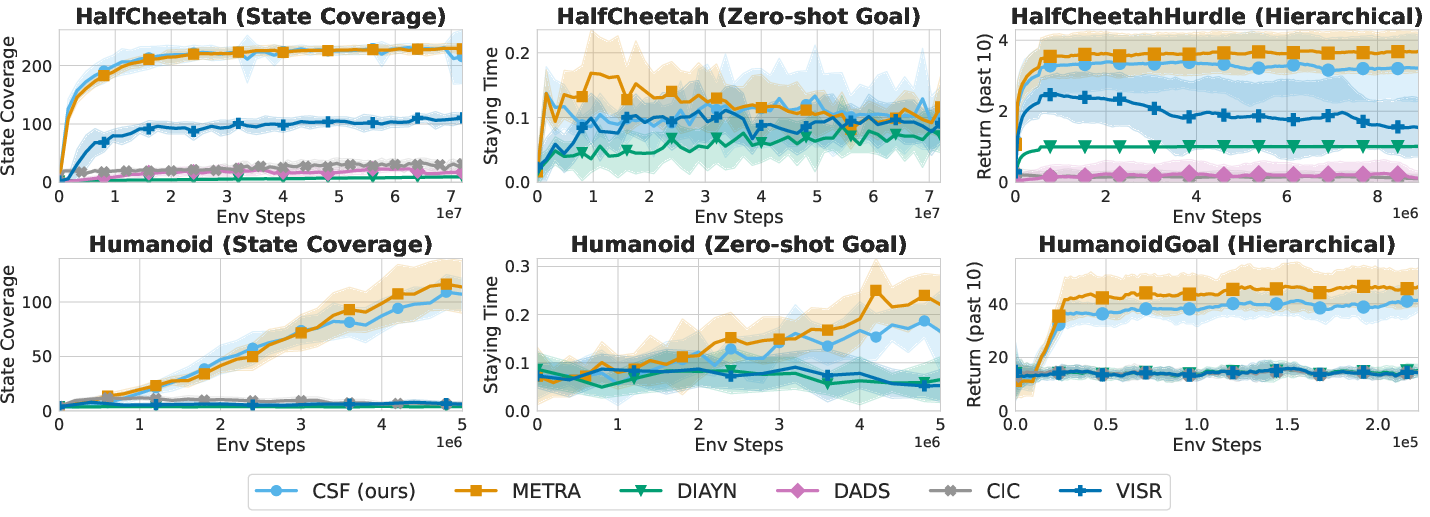

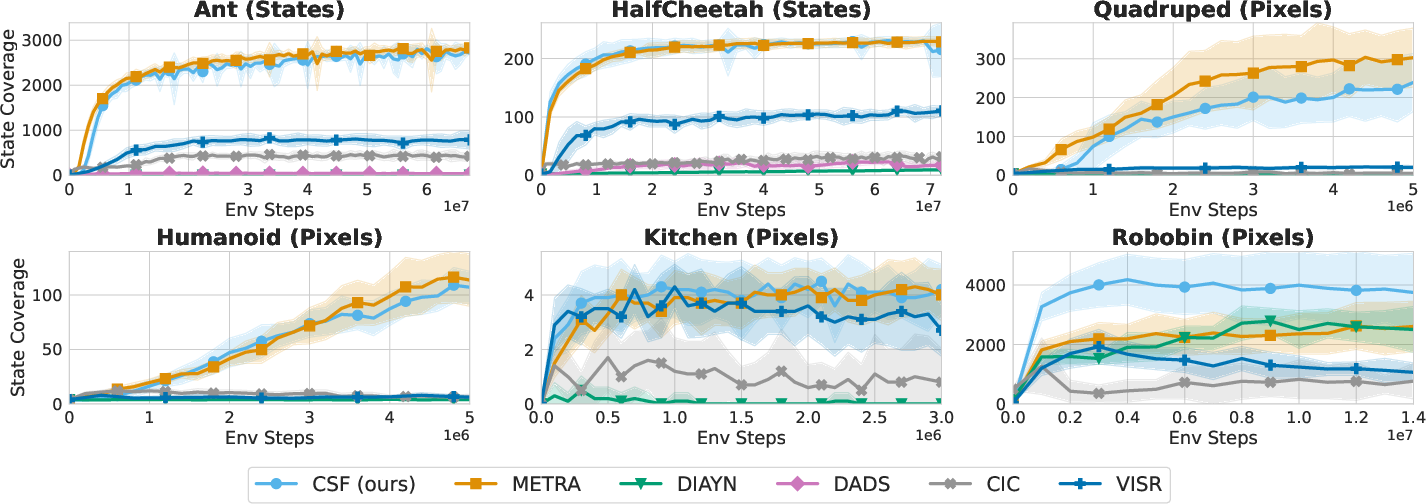

- Empirical results on continuous control benchmarks validate that CSF achieves comparable or superior performance in state coverage, goal reaching, and hierarchical control.

The paper "Can a MISL Fly? Analysis and Ingredients for Mutual Information Skill Learning" (2412.08021) provides a comprehensive theoretical and empirical analysis of recent advances in unsupervised skill discovery in reinforcement learning (RL), with a particular focus on the relationship between mutual information skill learning (MISL) and the Wasserstein-based METRA algorithm. The authors introduce a new algorithm, Contrastive Successor Features (CSF), and demonstrate that it matches the performance of METRA while offering a simpler, theoretically grounded approach.

Theoretical Foundations and Reinterpretation of METRA

The paper begins by revisiting the foundations of MISL, which aims to learn a diverse set of skills by maximizing the mutual information (MI) between latent skills and state transitions. The canonical MISL objective is:

maxπIπ(S,S′;Z)

where S and S′ are consecutive states, Z is a latent skill variable, and π is the skill-conditioned policy. This is typically operationalized via variational lower bounds and alternates between updating a variational posterior q(z∣s,s′) and the policy π.

The authors critically analyze METRA, a recent state-of-the-art method that replaces MI maximization with a Wasserstein dependency measure (WDM) and enforces a 1-Lipschitz constraint on the state representation ϕ. They show that, in practice, METRA's representation learning objective is nearly equivalent to a contrastive InfoNCE-style loss, and that the Wasserstein constraint can be interpreted as a quadratic approximation to the negative term in the contrastive lower bound.

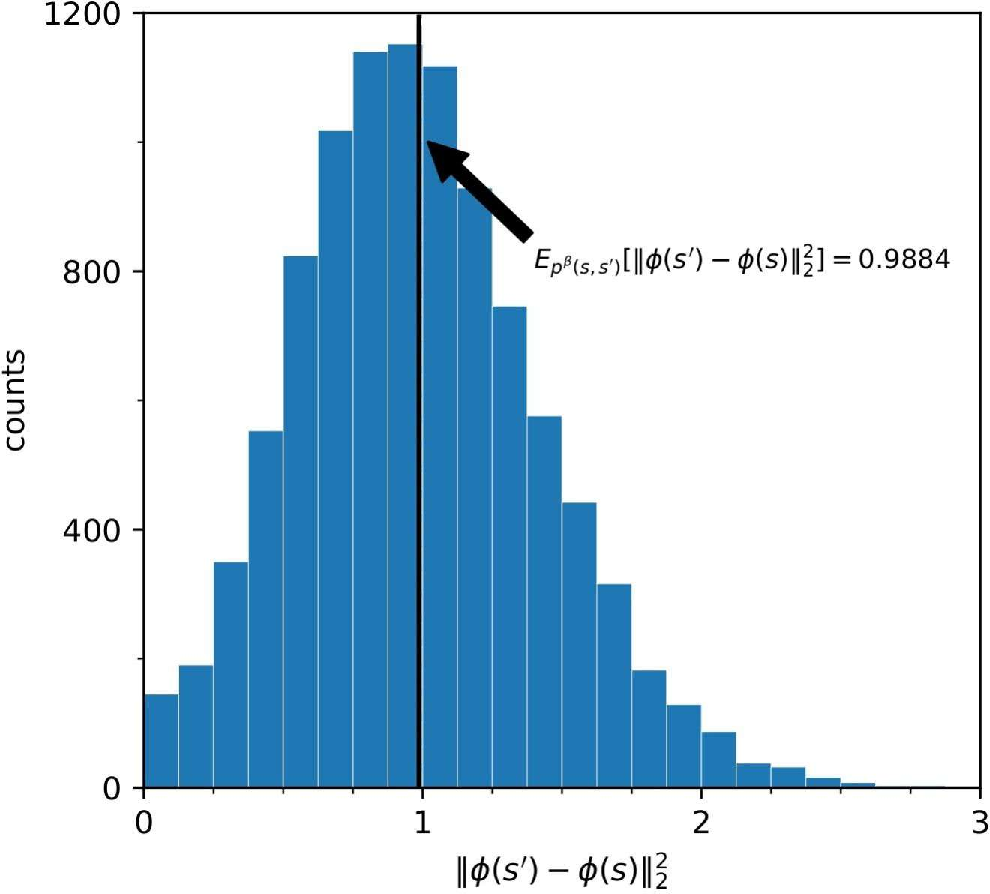

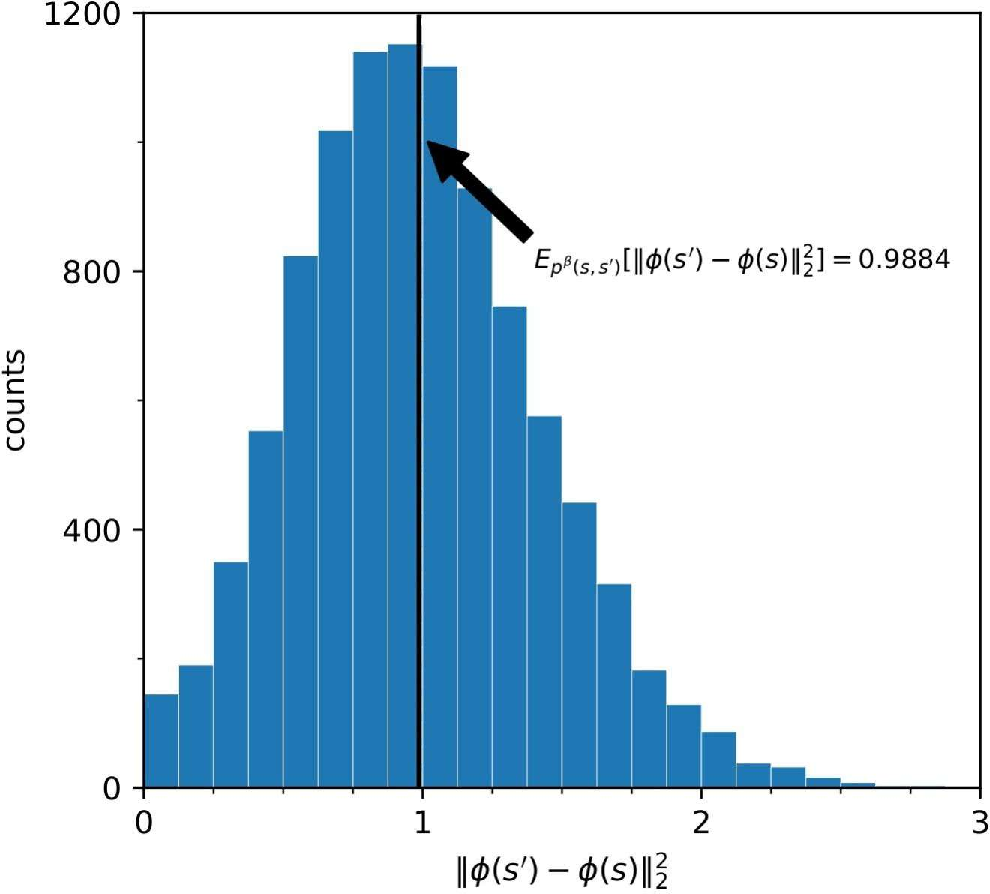

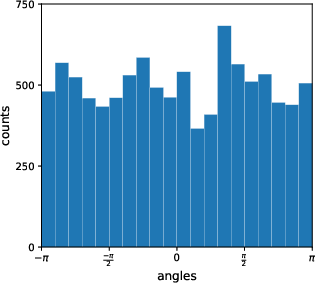

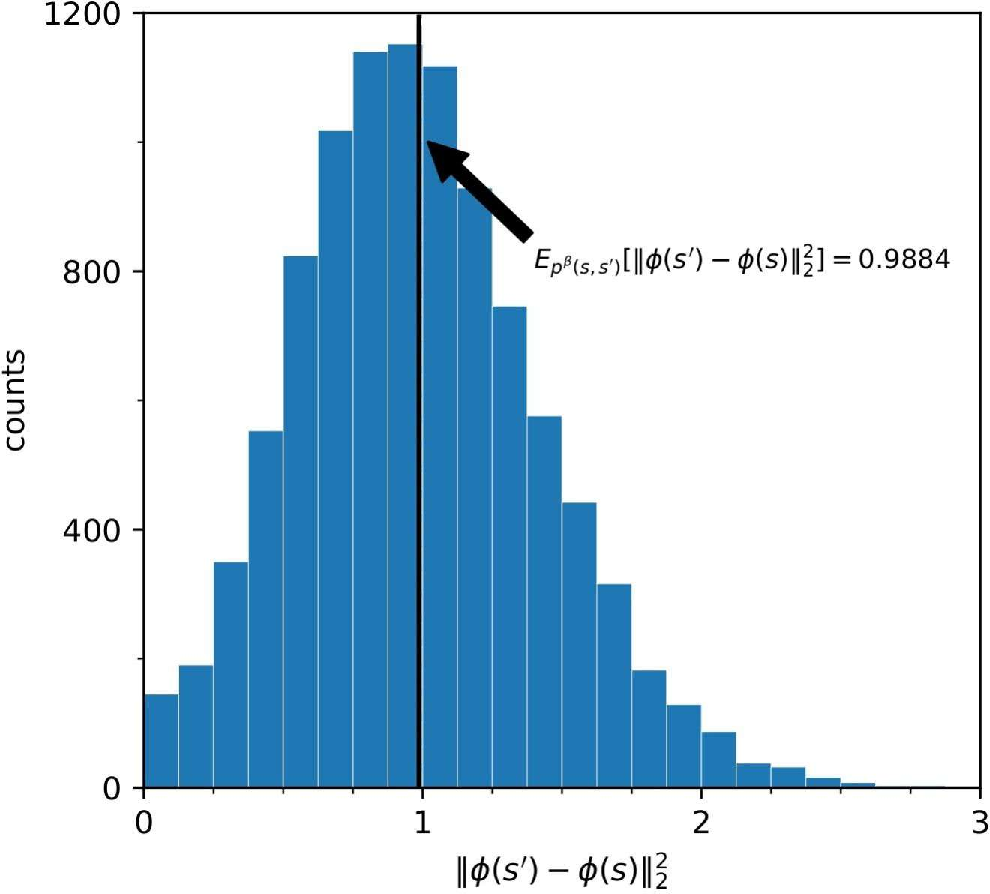

Figure 1: The expected constraint imposed by METRA on the squared norm of representation differences, which converges to 1 in practice.

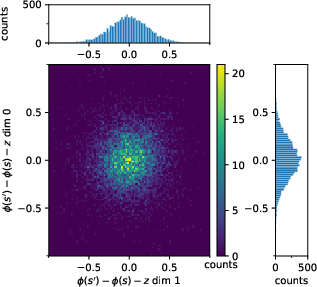

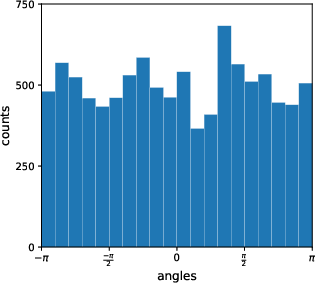

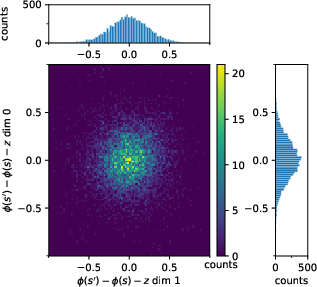

This reinterpretation is empirically validated: the learned representations under METRA satisfy the expected constraint E[∥ϕ(s′)−ϕ(s)∥2]=1 (Figure 1), and the distributional properties of the learned representations match those of contrastive learning.

Contrastive Successor Features (CSF): Algorithmic Simplicity and Theoretical Clarity

Building on this analysis, the authors propose CSF, which directly maximizes a contrastive lower bound on Iπ(S,S′;Z) for representation learning, and uses successor features for policy learning. The key steps are:

- Representation Learning: Optimize the contrastive lower bound:

E(s,s′,z)[(ϕ(s′)−ϕ(s))⊤z]−E(s,s′)[logEz′e(ϕ(s′)−ϕ(s))⊤z′]

This avoids the need for dual gradient descent and the explicit Wasserstein constraint.

- Policy Learning: Use the intrinsic reward r(s,s′,z)=(ϕ(s′)−ϕ(s))⊤z and learn a vector-valued critic (successor features) ψ(s,a,z), updating via temporal difference learning.

- Algorithmic Simplicity: CSF eliminates several hyperparameters required by METRA (e.g., dual variable initialization, slack variables), and is easier to implement and tune.

Empirical Analysis: Ablations and Benchmark Comparisons

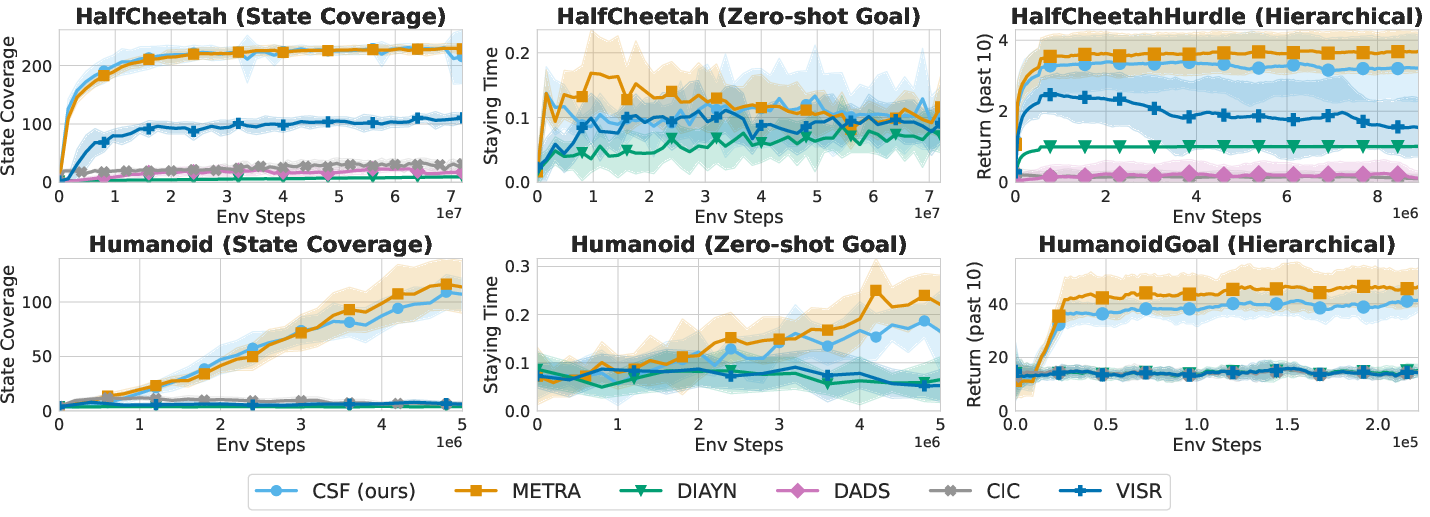

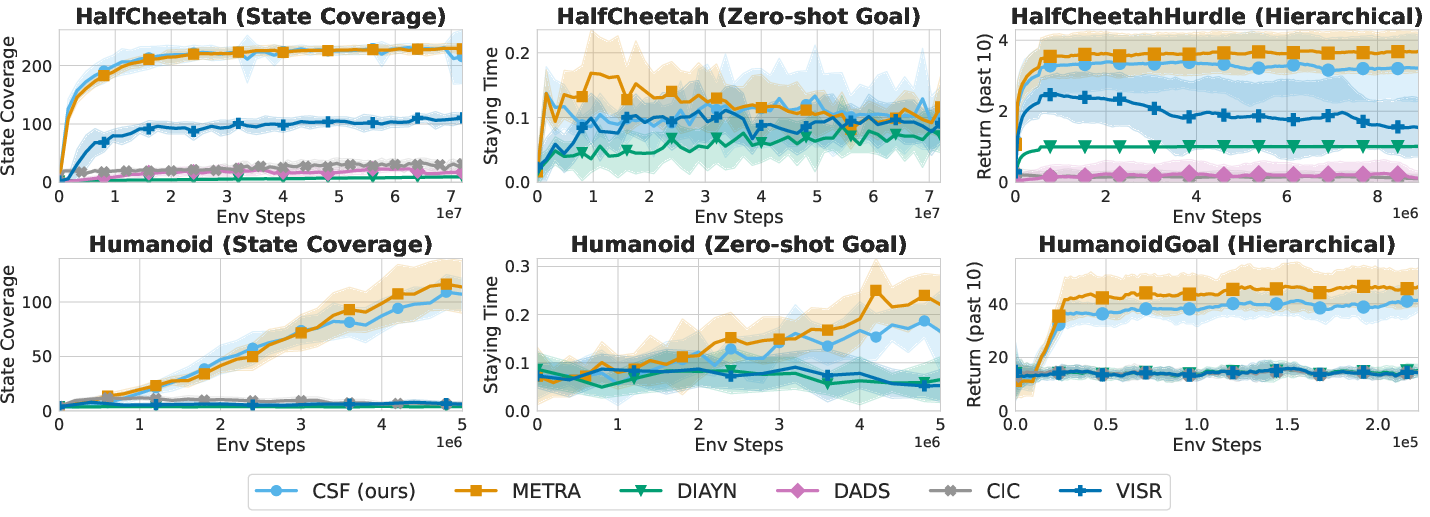

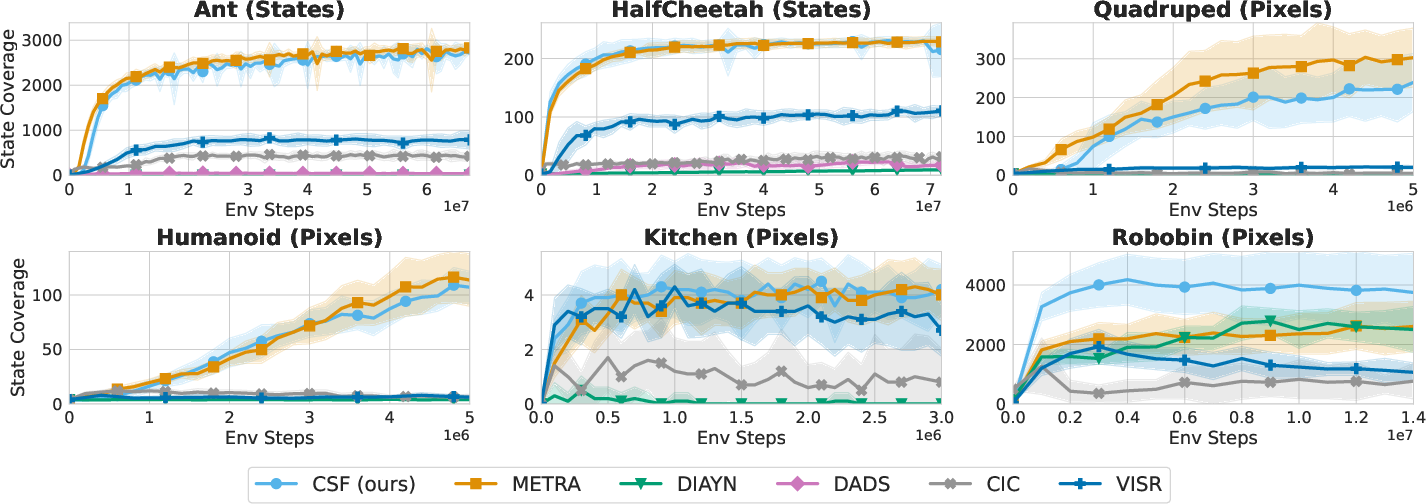

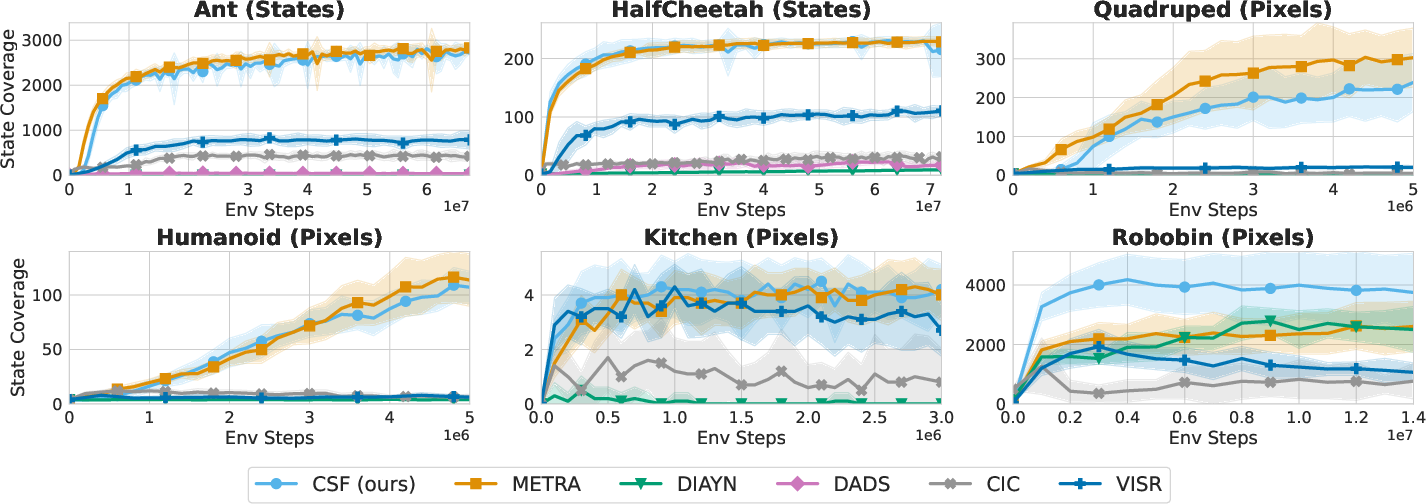

The paper presents extensive empirical results on standard continuous control benchmarks (Ant, HalfCheetah, Quadruped, Humanoid, Kitchen, Robobin), evaluating state coverage, zero-shot goal reaching, and hierarchical control.

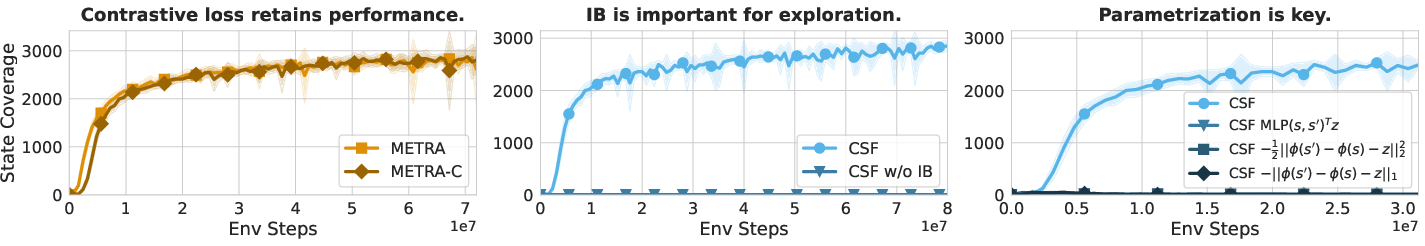

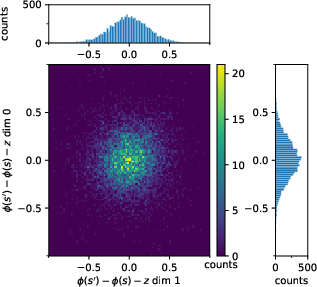

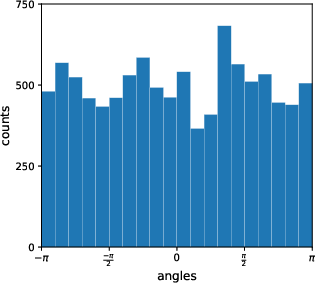

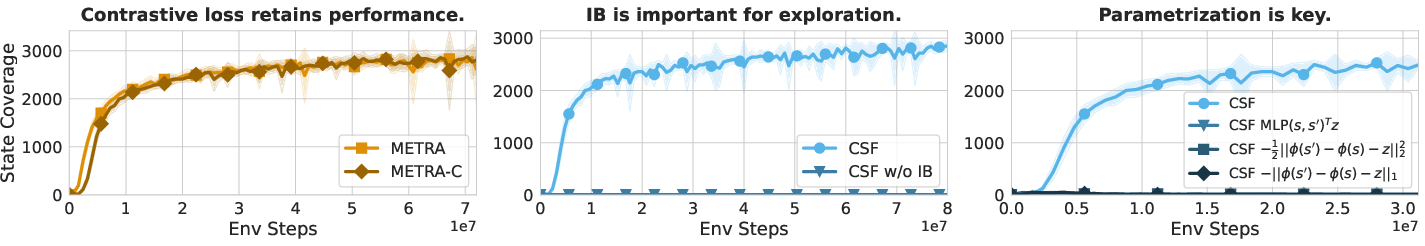

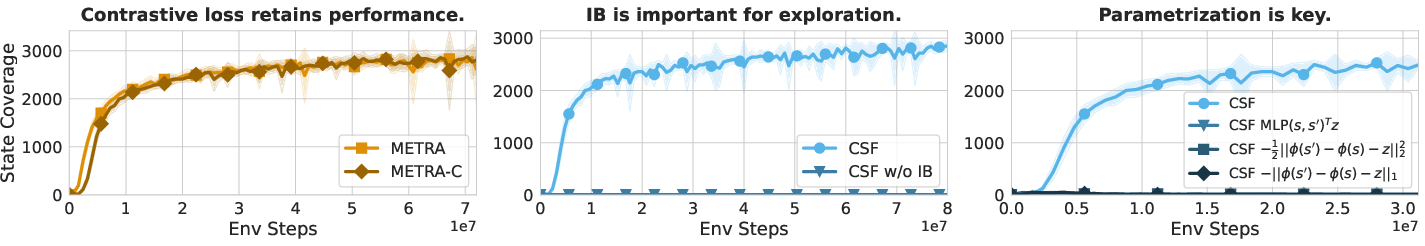

Figure 2: Ablation studies. Replacing the METRA representation loss with a contrastive loss retains performance. Using an information bottleneck for the intrinsic reward is critical. The choice of parameterization is crucial for performance.

Ablation studies (Figure 2) reveal several key findings:

- Contrastive Loss Suffices: Replacing METRA's representation loss with a contrastive loss does not degrade performance.

- Information Bottleneck: Using an information bottleneck (i.e., removing the anti-exploration term from the MI lower bound) is essential for effective skill discovery.

- Parameterization Sensitivity: The inner product parameterization (ϕ(s′)−ϕ(s))⊤z is critical; alternative parameterizations (e.g., MLP, Gaussian/Laplacian kernels) lead to catastrophic performance drops.

Figure 3: CSF performs on par with METRA across state coverage, zero-shot goal reaching, and hierarchical control benchmarks.

Figure 4: State space coverage. CSF matches or exceeds METRA on most tasks, with a notable advantage in Robobin.

Figure 5: Goal reaching. CSF achieves strong performance, outperforming DIAYN and VISR, but slightly lagging METRA on some tasks.

Figure 6: Hierarchical control. CSF is competitive with METRA, outperforming it on AntMultiGoal but underperforming on QuadrupedGoal.

Practical Implementation Considerations

- Resource Requirements: CSF and METRA have similar computational footprints, but CSF is easier to tune due to fewer hyperparameters.

- Scaling: Both methods are sensitive to the skill dimension; careful tuning is required for optimal performance.

- Deployment: CSF's reliance on standard contrastive learning and successor features makes it amenable to integration with existing RL pipelines and scalable to large datasets.

- Limitations: Both methods struggle in highly complex, partially observable, or discrete action environments (e.g., MiniHack), and their scalability to large-scale, real-world domains (e.g., BridgeData V2, YouCook2) remains an open question.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The paper's analysis challenges the necessity of moving beyond mutual information maximization for unsupervised skill discovery. It demonstrates that, with appropriate parameterization and the use of an information bottleneck, MI-based methods can match the performance of more complex alternatives like METRA. This has several implications:

- Theoretical Clarity: The equivalence between METRA and contrastive MI maximization clarifies the role of representation constraints and the importance of the information bottleneck in skill learning.

- Algorithmic Design: Simpler, theoretically grounded algorithms like CSF are preferable when they match or exceed the performance of more complex methods.

- Future Directions: Open questions include scaling MISL to high-dimensional, partially observable, or discrete domains, and leveraging large-scale offline datasets for pretraining transferable skills and representations.

Conclusion

The paper provides a rigorous analysis of the relationship between Wasserstein-based and mutual information-based skill discovery methods, demonstrating that the former can be interpreted as a special case of the latter. The proposed CSF algorithm achieves state-of-the-art performance with greater simplicity and theoretical transparency. The results suggest that mutual information maximization, when properly instantiated, remains a robust foundation for unsupervised skill discovery in RL. Future work should address the empirical scaling limits of these methods and their applicability to more complex, real-world domains.