- The paper provides a comprehensive evaluation of Estonia's digital voting system by analyzing its architecture, voter authentication via national ID cards, and performance metrics.

- It details the use of public key cryptography, dual-device verification, and extensive log auditing to secure vote integrity across multiple elections.

- The study highlights rising adoption rates, with internet voting participation increasing from 1.9% to over 30% in key national elections.

Overview of E-voting in Estonia

The paper "E-voting in Estonia" (1606.08654) provides a comprehensive analysis of the Estonian internet voting system, covering its historical context, its operational frameworks, and its reception both domestically and internationally. It assesses the systemic components, challenges, and performance metrics, thereby providing valuable insights into one of the world's most long-standing e-voting implementations.

Electoral Framework in Estonia

Estonia's parliamentary structure, known as the Riigikogu, plays a critical role in the electoral processes, with 101 members elected every four years. The country's voting methods include traditional in-person voting as well as the innovative internet voting system introduced in 2005. This system complements various types of voting in municipal and European Parliament elections, with procedural mechanisms like the d'Hondt method utilized for seat allocation.

Key to facilitating Estonia's e-voting is the national ID card, which provides secure digital authentication and signing capabilities. This infrastructure underpins the integrity of the internet voting system by ensuring reliable voter identification.

System Architecture and Components

Estonian internet voting leverages the principles of public key cryptography. A voter's ballot is encrypted with the election system's public key and digitally signed using the voter's private key from their national ID card. The system's design prioritizes simplicity and security comparability with paper-based voting, employing basic but trusted technologies over newer, less-tested mechanisms such as mix-nets.

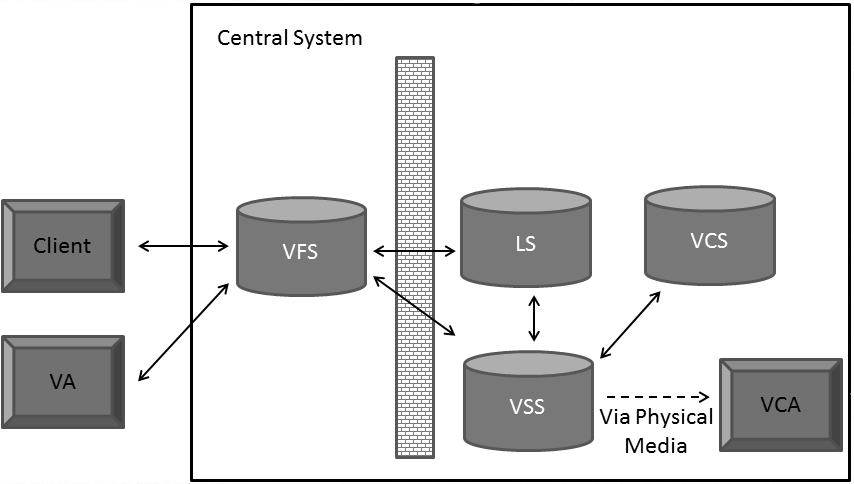

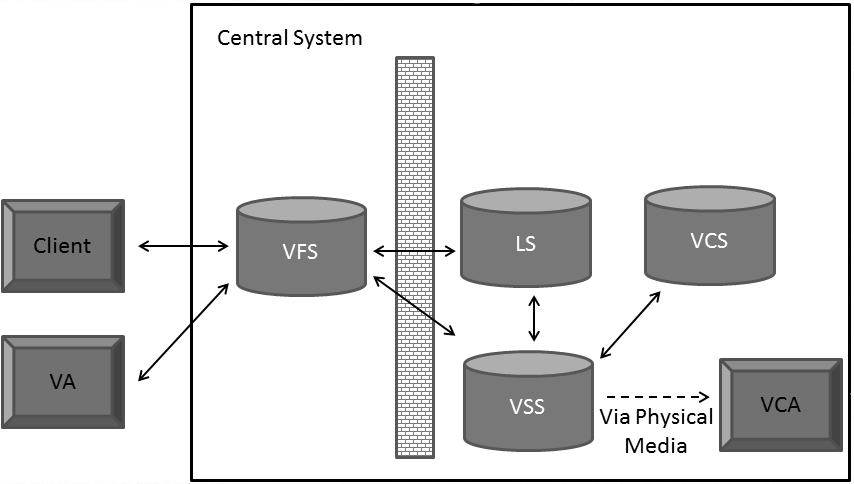

The architecture comprises several core components like the Voting Application (client), Verification Application (VA), Vote Forwarding Server (VFS), and Vote Storage Server (VSS), among others. These components interact to authenticate voters, manage ballots, and ensure secure communication between systems.

Figure 1: System Components illustrating the interconnected infrastructure of the Estonian internet voting system.

Verification and Security Measures

The system includes a verification application that permits voters to confirm their vote's storage via a separate device, enhancing security by using dual-device verification. While the system is theoretically susceptible to coercion, practical measures, including limited-time verification and lack of end-to-end universal verifiability, mitigate these risks. Auditing employs extensive log comparison to verify congruence between stored and processed votes, although these logs are vulnerable to tampering by sophisticated adversaries.

Criticisms and Reception

The Estonian e-voting system has faced academic scrutiny over potential vulnerabilities, including risks associated with card readers and reliance on logging for security assurances. Studies have criticized procedural lapses and the lack of transparency. However, the Estonian National Electoral Committee maintains confidence in its safeguards against these vulnerabilities, citing procedural integrity and voter satisfaction.

Despite criticisms, public confidence in the system is high, with significant voter adoption across multiple election cycles. Reports from international observation missions confirm this acceptance, albeit alongside noted concerns.

Quantitative data highlights the system's performance over a decade. Internet voting participation has steadily increased, demonstrating scalability and dependent reliability. For instance, usage surged from 1.9% in initial local elections to over 30% in subsequent Riigikogu and European Parliament elections. This growth underlines the system's robustness in handling increasing voter loads while exhibiting negligible operational faults.

Conclusion

Estonia's internet voting system represents a notable case study in the global context of e-voting. Although not devoid of theoretical criticisms, its practical execution over several election cycles has shown resilience and efficacy. The system's future likely involves evolving technological safeguards to address latent vulnerabilities and ensure sustained public trust and engagement. Despite challenges, Estonia's experience offers critical insights for other nations exploring similar digital voting strategies.