- The paper introduces a state-indicator framework to predict both single and sequential events, bypassing traditional hazard-based approaches.

- It employs discrete-time Markov models and ARIMA forecasts to effectively incorporate time-dependent covariates for improved prediction accuracy.

- Empirical results in phenology demonstrate reduced RMSE and MAE as more in-season covariate data is observed, enhancing predictive precision.

Predicting Sequences of Progressive Events Times with Time-dependent Covariates

Introduction and Motivation

This paper develops a principled statistical framework for predicting sequences of progressive event times in the presence of external, time-dependent covariates. The key innovation is to model the process via state indicators rather than through the hazard function directly, as is typical in classical event-history and survival analysis. This approach allows for enhanced incorporation of all available information in the covariate process—especially relevant where covariates exhibit strong temporal structure, such as dominant seasonality in phenological applications.

By abstracting away from hazard-based models and leveraging a discrete-time, state-indicator representation, the method enables straightforward construction of prediction rules and likelihood functions. Moreover, it avoids stringent and often unrealistic distributional assumptions for the time-to-event random variables. This methodology is developed both for single and sequential (multiple) progressive events.

Model Construction: Single and Multiple Events

Single Event Case

The foundation is a discrete-time Markov chain model, where the state variable Yi,t for subject i indicates whether an event has occurred by time t. The probability law for Yi,t, conditioned on time-dependent covariates Xi,t, is

P(Yi,t=1∣Yi,t−1=0,Xi,t)=g−1(β⊤Xi,t)

where g is a link function (e.g., logit or probit), and β is a parameter vector. Temporal dependence is accounted for by restricting the dependence to a window of lagged covariates. The likelihood is constructed by combining the product of "no event" histories and the event occurrence, facilitating both maximum likelihood and Bayesian parameter estimation. The extension to right-censored data adopts the standard non-informative censoring formulation, modifying the likelihood accordingly.

Multiple Event Sequences

For S progressive, ordered events per subject, the model extends to a finite-state space, where at any time t, the state variable Yi,t denotes which of the S+1 possible event states has occurred. Transition probabilities between states are modeled explicitly, with careful consideration that the (non-Markovian) process now requires conditioning on previous event times, state, and past covariates. The regression parameterization is enforced using polynomial or linear functions in the covariates and lagged event times (embedded to ensure fixed-dimensional parameter space across varying states).

The likelihood for parameter estimation in the sequential event model is substantially more complex due to crossing dependencies, and additional assumptions are required to maintain computational tractability.

Prediction Methodology

Prediction targets the timing of future event occurrences, conditional on observed (or forecasted) covariate trajectories. If the realized future covariates are unknown, their predictive distributions are incorporated using Monte Carlo integration. Both plug-in (using maximum likelihood estimates for parameters) and fully Bayesian prediction (integrating over the posterior distribution of parameters) strategies are presented.

Importantly, in the context of time-dependent covariates, predictive accuracy is strongly modulated by the quality of the covariate forecasting model. The paper leverages separate ARIMA models for forecasting temperature in agricultural datasets but notes this as a major source of predictive uncertainty.

Empirical Study: Phenological Event Prediction

The method is empirically assessed on a compelling real-world problem: predicting the bloom dates of pear trees using daily temperature series aggregated into cumulative growing degree-days (AGDD), with the thermal base parameter Tbase also estimated from the data.

A rolling leave-one-year-out cross-validation is applied from 1937 to 1964. At each prediction step, the ARIMA(3,0,1) model is used to generate 1000 stochastic temperature scenarios, which feed into the event prediction model to yield predictive distributions over bloom date.

Strong empirical results include:

- RMSE of predicted bloom date: 5.65 days (with full temperature uncertainty).

- MAE: 4.36 days.

- Empirical 95% prediction interval coverage: 99% (noting some overdispersion due to the ARIMA model’s treatment of residual structure).

- Reducing temperature forecast variance (for diagnostic purposes) yields tighter prediction intervals and improved calibration.

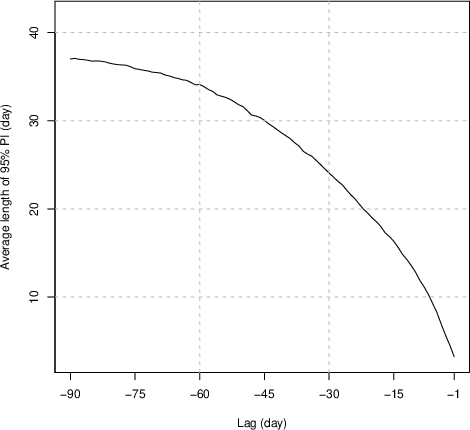

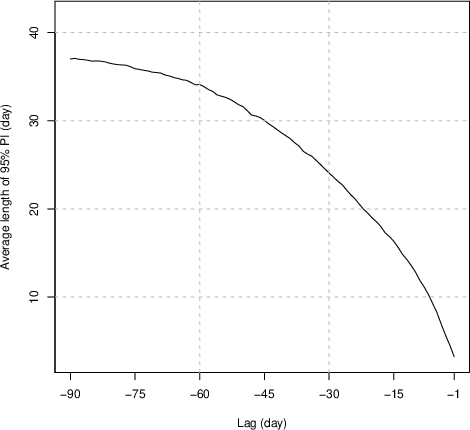

Critically, the MAE and prediction interval length decrease systematically as more in-season temperature data are observed, demonstrating the method’s sensitivity to covariate information accumulation.

Figure 1: Change of the MAE with the change of lag. The point prediction becomes more accurate when time approaches the bloom date.

Figure 2: Change of the average length of 95\% PIs with the change of lag. The predictive uncertainty decreases when time approaches the bloom date.

When the future covariate trajectory is assumed known (as an upper performance bound), the method delivers an RMSE of 2.64 days and an MAE of 1.89 days, with mean PI length reduced to 9.21 days.

Numerical Estimation and Inference

Parameter estimation is conducted via likelihood maximization with a logistic link function; the presence of the non-smooth AGDD base (Tbase) is acknowledged as complicating theoretical analysis of MLE asymptotics. Nevertheless, extensive simulation studies support estimator consistency and effective coverage properties for bootstrap-derived confidence intervals, though minor bias is noted.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Prospects

This modeling framework demonstrates substantial utility for sequential event prediction in domains where covariates are high-frequency, nonstationary, and critically informative to the timing process. Its application to agricultural phenology is direct, but the paradigm extends to biomedical, reliability, and other event-history contexts characterized by progressive, irreversible events governed by external time-varying processes.

Several theoretical and practical limitations are highlighted:

- The model assumes state-indicator process time-homogeneity (parameters do not vary with time); relaxing this could yield greater flexibility, particularly under nonstationary covariate regimes.

- Disallowing simultaneous event occurrences at coarse time resolutions is restrictive and motivates further model generalizations.

- Predictive performance is entangled with the fidelity of covariate forecasting; improvements in this upstream modeling will yield direct gains in uncertainty quantification for event timing.

Conclusion

This work establishes a robust, generalizable method for predicting progressive event sequences with high-dimensional, time-dependent covariates, bypassing the need for explicit hazard modeling. Empirical analyses confirm high predictive accuracy, especially as the event of interest approaches and covariate realization uncertainty diminishes. Extensions to enhance time-inhomogeneity, accommodate concurrent events, and integrate flexible covariate forecasting represent promising avenues for continued research.