Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code

Abstract: We introduce Codex, a GPT LLM fine-tuned on publicly available code from GitHub, and study its Python code-writing capabilities. A distinct production version of Codex powers GitHub Copilot. On HumanEval, a new evaluation set we release to measure functional correctness for synthesizing programs from docstrings, our model solves 28.8% of the problems, while GPT-3 solves 0% and GPT-J solves 11.4%. Furthermore, we find that repeated sampling from the model is a surprisingly effective strategy for producing working solutions to difficult prompts. Using this method, we solve 70.2% of our problems with 100 samples per problem. Careful investigation of our model reveals its limitations, including difficulty with docstrings describing long chains of operations and with binding operations to variables. Finally, we discuss the potential broader impacts of deploying powerful code generation technologies, covering safety, security, and economics.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

What this paper is about (in simple terms)

This paper introduces Codex, a computer program based on GPT-style AI that’s trained to write code, mainly in Python. The authors built a new test called HumanEval to check if Codex can write small, correct functions from short descriptions (called docstrings). They show that Codex can solve a good number of problems—especially if you let it try multiple times—and they carefully discuss where it works well, where it struggles, and what the risks are.

What questions the researchers asked

They set out to answer a few big, easy-to-understand questions:

- If we train a LLM specifically on lots of public code, will it get good at writing code?

- How can we fairly test whether the code it writes actually works?

- Do bigger models do better, and does letting the model try multiple times help?

- Can we pick a good answer without running tests every time?

- Can fine-tuning (extra training on carefully chosen coding tasks) make it better?

- What are the limits and risks of using code-writing AI?

How they tested their ideas (methods explained simply)

Think of Codex as a very advanced “auto-complete” for code:

- It looks at a short English description of what a function should do (the docstring).

- Then it tries to write the function that matches that description.

Here’s how the researchers checked its abilities:

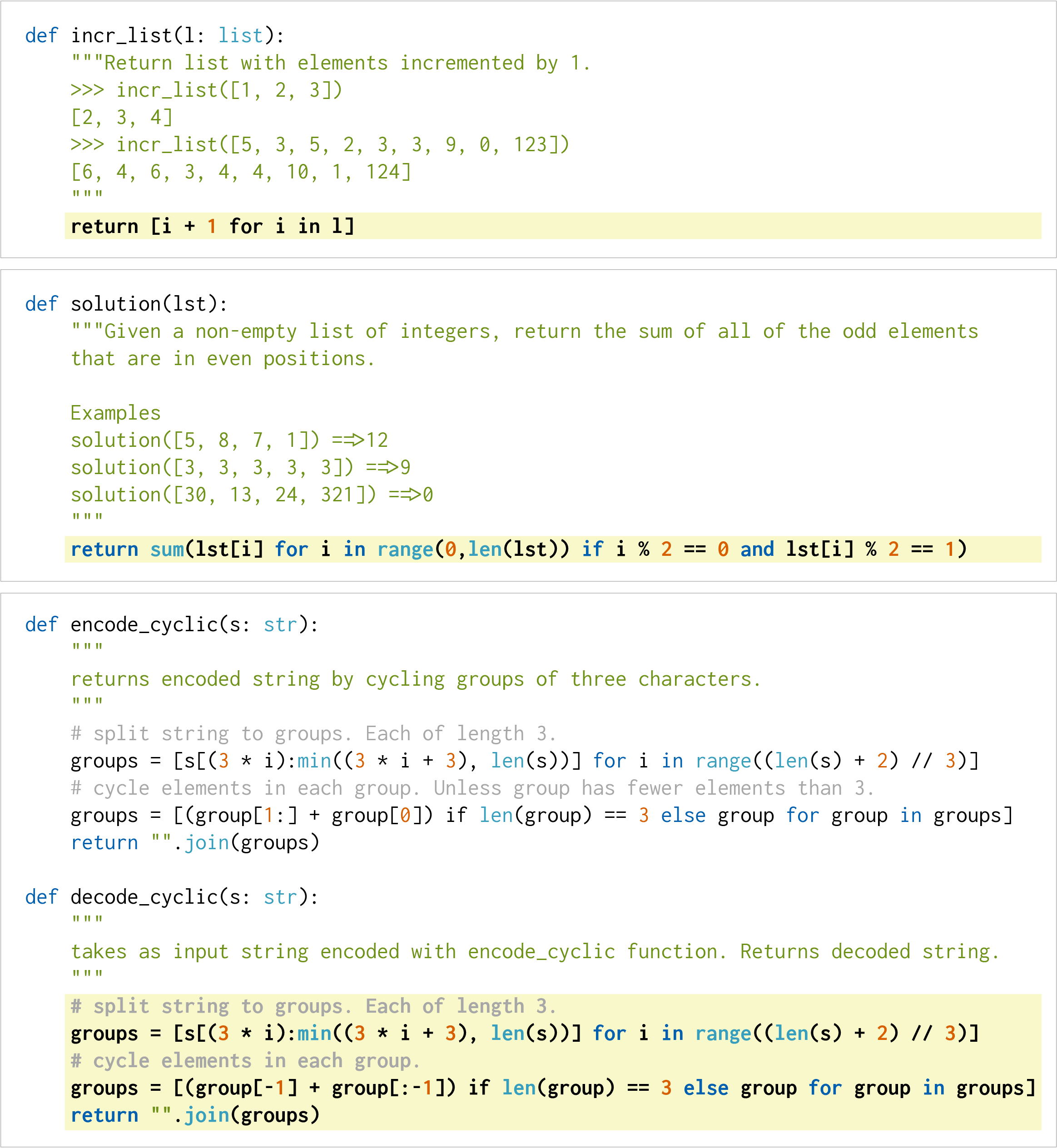

- HumanEval: They created a set of 164 small, original programming problems. Each problem has:

- A function name and description (docstring)

- Hidden tests (unit tests) that check whether the function truly works

- Unit tests: Like a checklist. If the function passes all tests, it’s considered correct.

- Safe sandbox: They ran the AI’s code in a safe “sandbox” so bad code couldn’t harm the computer.

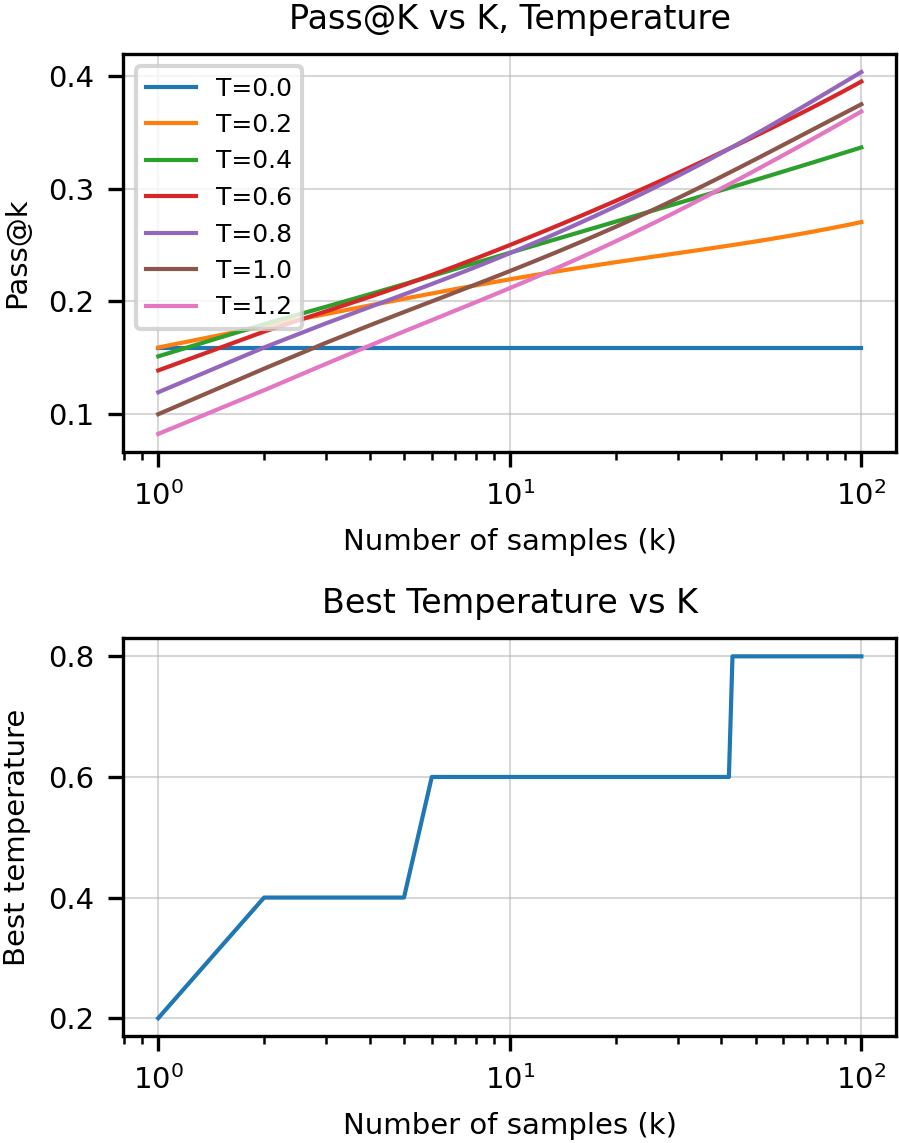

- Multiple tries (“pass@k”): Instead of just one shot, they sometimes let Codex try several times (like throwing multiple darts). If any try passes the tests, it counts as a success. “pass@1” means one try; “pass@100” means up to 100 tries.

- Sampling temperature: This controls how “adventurous” the AI’s suggestions are. Low temperature = safer, more predictable answers; high temperature = more variety and creativity. Higher temperatures helped when taking many tries because it produced more diverse solutions.

- Picking a single best suggestion: In real tools, you often show one suggestion. They tried a simple trick—choose the answer with the highest average “confidence” (mean log-probability). This worked better than picking randomly.

- Extra training (Codex-S): They also fine-tuned Codex on thousands of carefully collected function problems (from programming contests and from real projects’ tests) to make it even better at this specific task.

- Comparisons: They compared Codex against other models (like GPT-J and GPT-Neo) and a commercial code tool (Tabnine).

- Beyond coding-from-docstrings: They also trained a model (Codex-D) that writes docstrings from code, to explore safety and explainability.

- Other datasets: They tested on a tougher dataset (APPS) to see how it handles more complex, full-program problems.

Key terms in everyday language:

- LLM: A system that predicts what text (or code) comes next—like a smart auto-complete.

- Unit tests: Automatic checks that confirm the program does what it’s supposed to.

- Sandbox: A safe, locked environment for running untrusted code.

- pass@k: “Success if any of k tries works.”

- Log-probability: The model’s internal measure of how likely it thinks its answer is—used here as a rough “confidence” score.

What they found (main results)

Here are the most important results and why they matter:

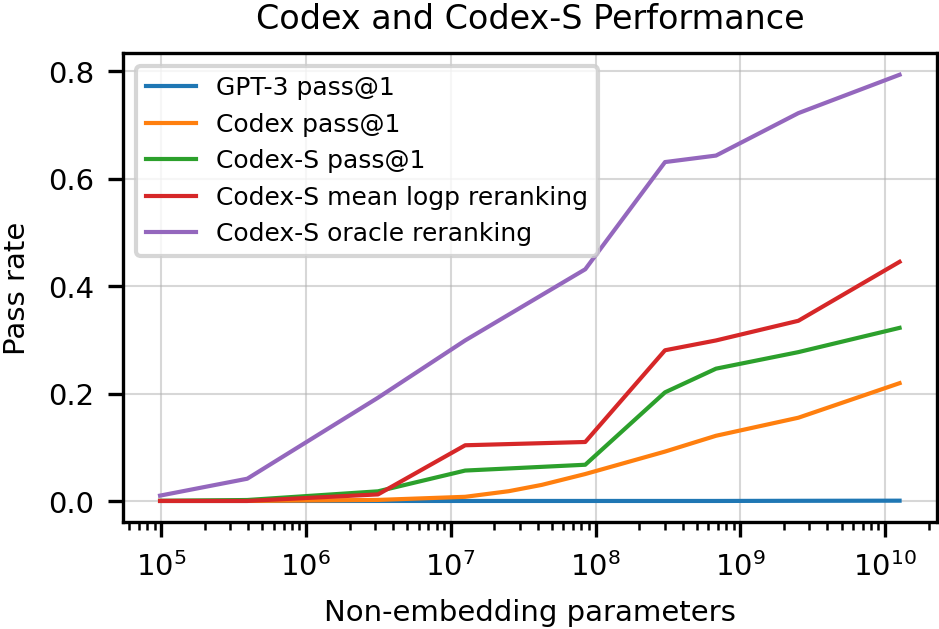

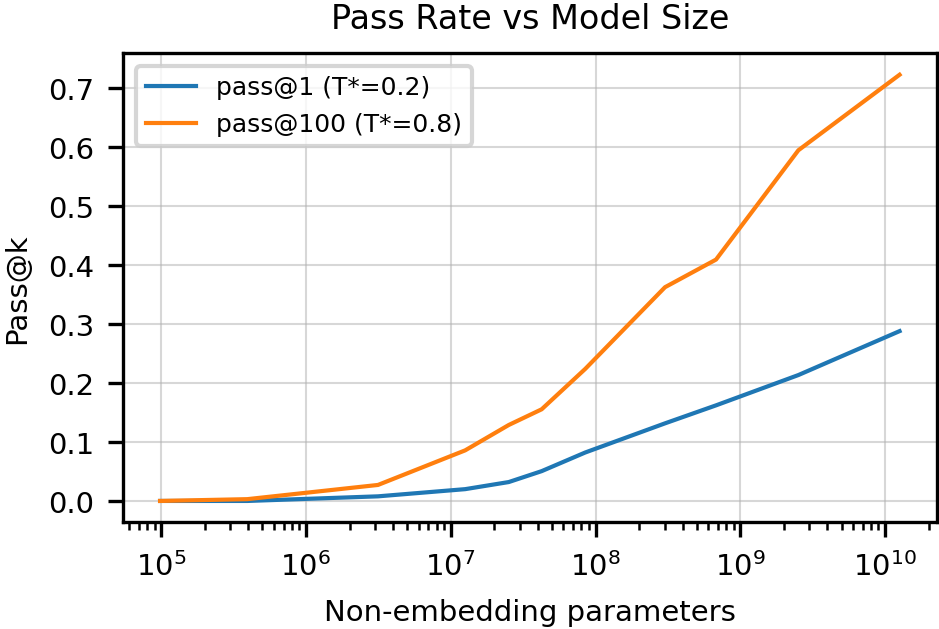

- Codex beats general LLMs at coding: On HumanEval, a 12-billion-parameter Codex solved about 28.8% of problems on the first try (pass@1). Similar-size general models solved almost none.

- Trying multiple times helps a lot: With 100 tries per problem, Codex solved about 70%+ of the set (77.5% for the fine-tuned version, Codex-S).

- Fine-tuning on the exact task helps: Codex-S (trained on many standalone function problems) did even better: 37.7% on first try and up to 77.5% with multiple tries.

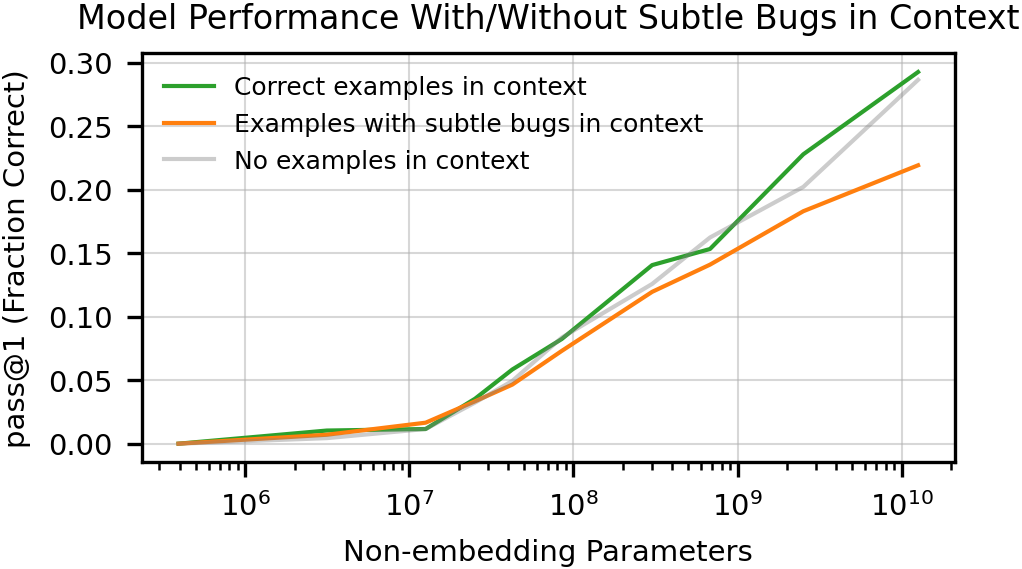

- Bigger models, better results: Performance generally improved as Codex got larger, following smooth scaling patterns.

- Picking one suggestion wisely helps: Choosing the suggestion with the highest average confidence beat random choice, which is helpful for tools that show a single completion.

- “BLEU” scores don’t reliably measure correctness: A text-similarity score like BLEU often didn’t match whether the code actually worked. Passing tests is what really matters.

- On tougher tasks (APPS), Codex needed many tries, and even then sometimes wrote solutions that worked but were too slow. Using public examples in the prompt and filtering candidates through basic checks helped.

Limits and weaknesses (what Codex struggles with)

The paper is clear that Codex isn’t perfect:

- Needs lots of training code: It learned from a huge amount of code—far more than most humans ever see.

- Long, complicated instructions: When the docstring described a long chain of steps, performance dropped sharply as the list grew.

- Mixing up variables and steps: Sometimes it applied the right operation to the wrong variable or forgot a step.

- Security and safety: Generated code can be wrong or insecure, so you must still review it. They built a sandbox to reduce risk while testing.

- Misalignment and over-reliance: The model may produce code that looks right but isn’t what you intended. Novices might trust it too much. As models get more capable, this risk can grow.

Why this matters

- Helpful coding assistant: Codex can speed up coding by suggesting functions, helping with boilerplate, and aiding learning.

- Better evaluation: The HumanEval benchmark and the pass@k metric show a fairer way to test code-writing AI: run the code and see if it passes tests.

- Direction for improvement: Fine-tuning on task-specific data greatly boosts performance. Picking one answer using confidence scores also helps.

- Caution is required: Even powerful AI can make subtle mistakes. Human oversight, good tests, and security practices remain essential.

- Broader impact: Tools like Codex can change how people learn and write code, but they also raise questions about safety, fairness, and potential misuse. The authors call for careful deployment and further research on reducing risks like misalignment and over-reliance.

Bottom line

Codex shows that training AI on lots of real code can produce a strong coding assistant that solves many programming tasks, especially if you let it try multiple times or fine-tune it on the exact types of problems you care about. But it isn’t a magic fix: its code must be tested and reviewed, it can be misled by complex instructions, and it can produce insecure or incorrect solutions. Used carefully, it can be a powerful aid; used blindly, it can cause problems.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.