- The paper introduces a comprehensive synthesis that bridges deep learning architectures with scientific discovery challenges, emphasizing iterative workflows and rigorous validation.

- It systematically categorizes core models and tasks—including supervised, sequential, graph, and generative methods—with detailed taxonomies and benchmarks.

- It advocates best practices like data augmentation, transfer learning, and interpretability to overcome data scarcity and methodological diversity in science.

A Survey of Deep Learning for Scientific Discovery

Overview and Motivation

The paper "A Survey of Deep Learning for Scientific Discovery" (2003.11755) presents a comprehensive synthesis of deep learning methodologies as deployed in scientific research. The authors systematically bridge the rapidly evolving deep learning landscape—spanning architectures, tasks, and training paradigms—with the pragmatic constraints and epistemic goals of scientific inquiry. A central thesis is that, while recent neural architectures have yielded qualitative improvements across machine learning domains, their adoption in the sciences is constrained not merely by computational resources but by the challenge of navigating the methodological diversity and adapting these technologies to data-constrained, interpretability-focused environments.

Deep Learning Workflow in the Scientific Context

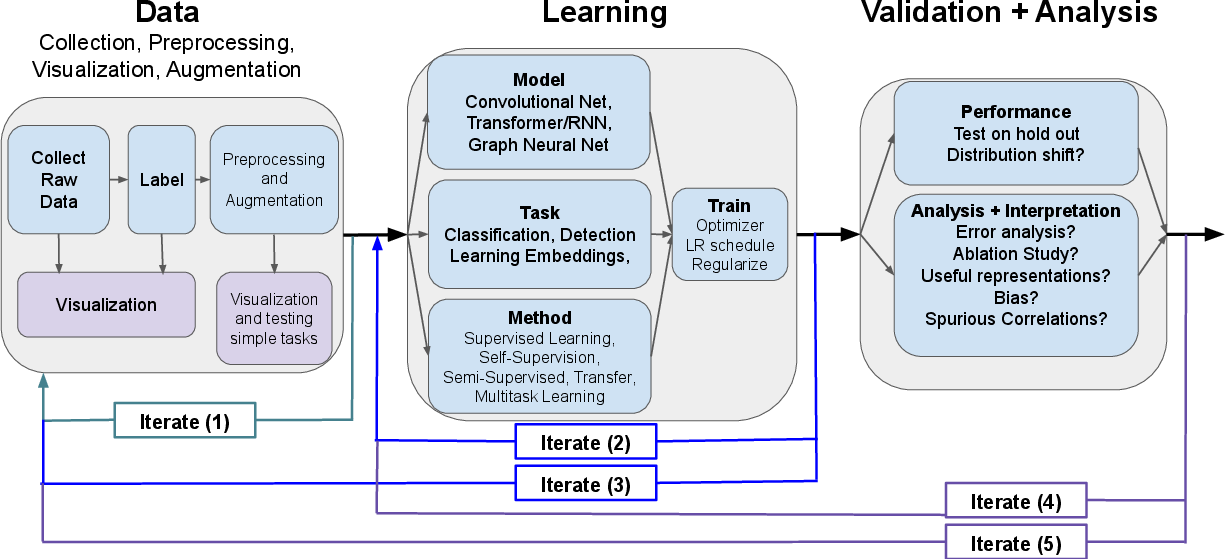

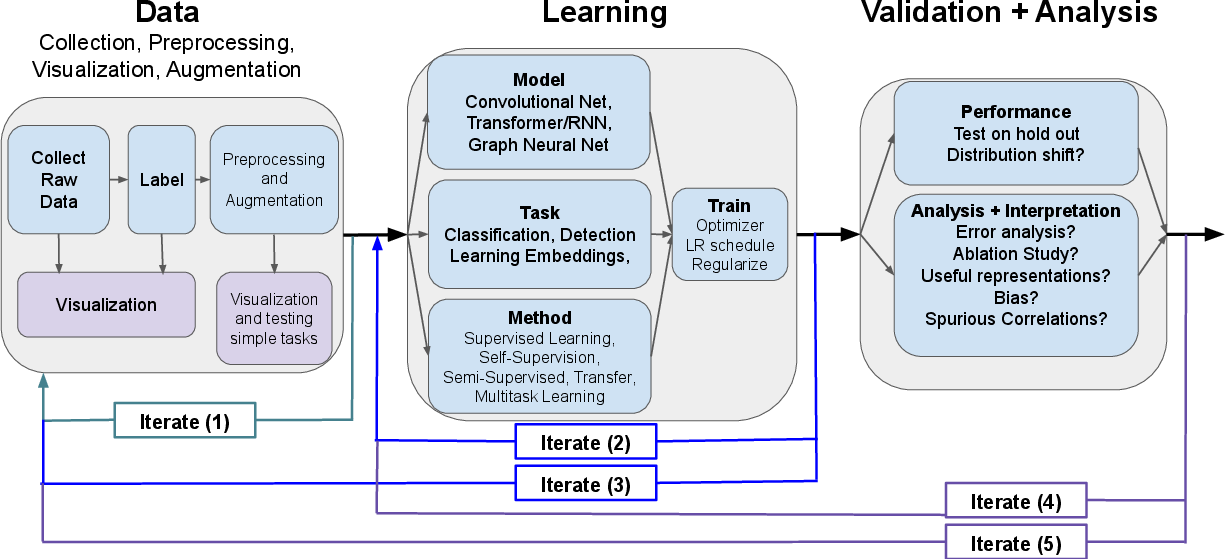

The survey formalizes the canonical deep learning workflow into three iterative phases: data acquisition/curation, model selection/training, and validation/analysis. In scientific contexts, these phases are highly intertwined, often requiring multiple iterations as insight from validation triggers redesigns in earlier stages—a paradigm illustrated in the presented workflow schematic.

Figure 1: Schematic of the iterative data–learning–validation workflow, emphasizing feedback loops central to scientific adaptation of deep learning pipelines.

This abstraction allows mapping diverse use cases—predictive modeling, mechanistic understanding, and data transformation—onto robust, extensible development practices while emphasizing the necessity for rigorous validation and error analysis, especially in the presence of dataset shift and implicit biases.

Core Deep Learning Models and Task Taxonomy

The survey provides technical summaries of fundamental architectures (MLPs, CNNs, RNNs, Transformers, GNNs) and their alignment with standard computer vision, sequential, and graph-structured tasks, highlighting the following insights:

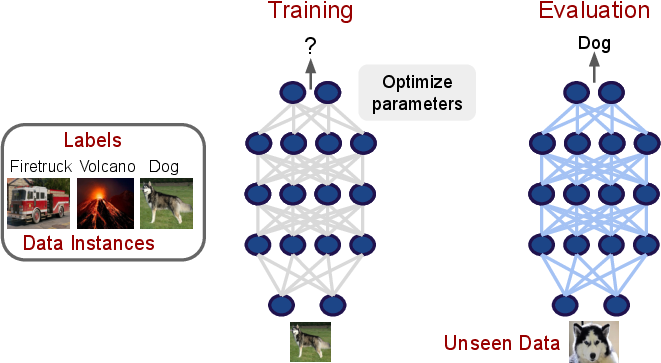

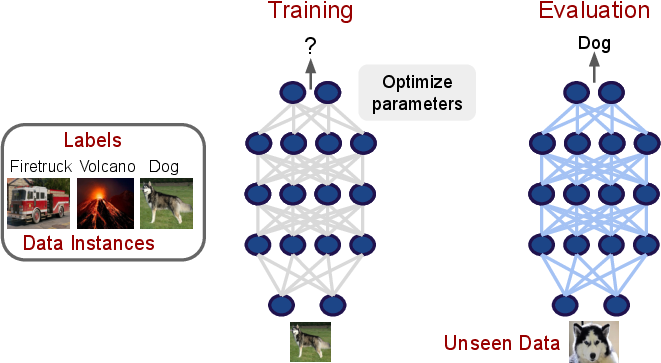

- Supervised Learning as a Fundamental Paradigm: Despite the proliferation of advanced methods, supervised learning and its derivatives (transfer learning, multitask learning, domain adaptation) remain the backbone of scientific DL applications. The survey dissects the training loop and its implications for model selection and evaluation.

Figure 2: The classic supervised learning paradigm, with emphasis on generalization to unseen instances—a core requirement for scientific discovery.

- Task Diversity: The taxonomy of visual tasks (classification, detection, semantic and instance segmentation, registration, super-resolution, pose estimation) is contextualized with model selection heuristics and references to standard benchmarks and open implementations.

Figure 3: Comparative overview of classification, detection, and segmentation tasks, recognizing the increased annotation requirement and spatial granularity for advanced tasks such as instance segmentation.

Figure 4: Schematic of pose estimation relevant for behavioral quantification in neuroscience and biology.

- Sequence and Graph Models: The articulation of architectures for sequential data (LSTM-based RNNs, sequence-to-sequence models, Transformers) and graphs (GNNs) is tightly coupled with discussion of language modeling, machine translation, and molecule/property prediction, making explicit the transferability of techniques across natural and scientific datasets.

Figure 5: Encoder-decoder sequence-to-sequence framework for machine translation, foundational for biological sequence modeling.

Figure 6: LSTM cell structure, denoting state propagation critical for variable-length sequential dependencies.

Figure 7: Visualization of Transformer attention blocks, highlighting direct context modeling for global dependency capture.

Reducing Data Dependence: Transfer, Self-Supervision, and Semi-Supervised Methods

A pivotal section addresses the data bottleneck often encountered in scientific applications:

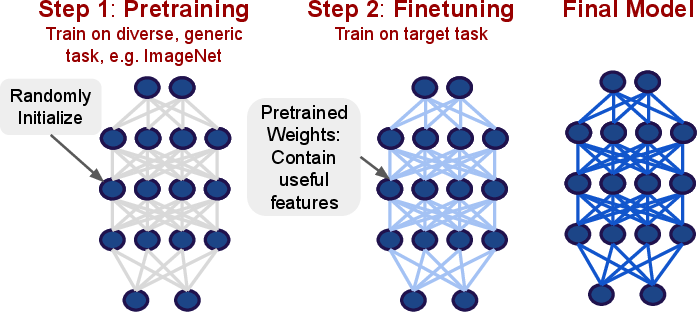

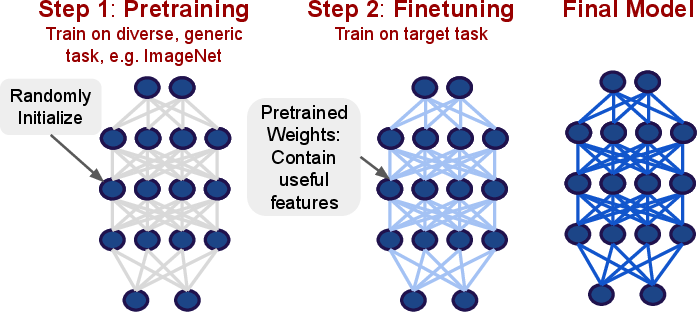

- Transfer Learning: Pretraining on diverse tasks (e.g., ImageNet, large text corpora) followed by fine-tuning on domain-specific data is established as the de facto protocol.

Figure 8: Two-phase transfer learning: pretraining on source domain, followed by fine-tuning for task and dataset adaptation.

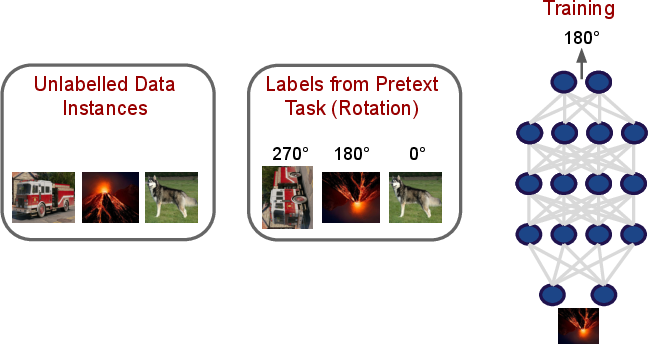

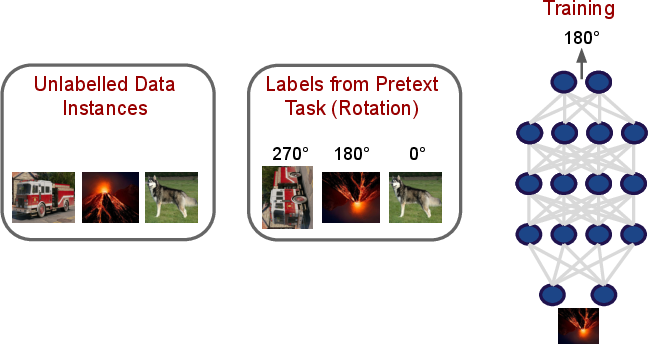

- Self-Supervised and Semi-Supervised Learning: The survey details paradigms where supervision arises from inherent structure in unlabeled data (e.g., rotation prediction, language modeling), and hybrid frameworks combining labeled and unlabeled examples, expanding applicability in limited-annotation regimes.

Figure 9: Self-supervised training leveraging pretext tasks, with learned representations transferable to downstream scientific tasks.

- Data Augmentation: Synthetic expansion via augmentations (e.g., mixup, Cutout, RandAugment) is advocated as essential in the overfitting-prone, low-sample, high-dimensional regime.

Figure 10: The mixup augmentation synthesizes new instances as convex combinations of existing samples and labels.

Model Interpretability and Scientific Insight

A defining requirement in scientific discovery is not only to predict but to understand. The survey offers a dual taxonomy:

- Feature Attribution/Explainability: Saliency maps, gradient-based approaches (e.g., SmoothGrad), and perturbation/ablation studies yield per-sample explanations of model decision-making.

Figure 11: SmoothGrad visualization, improving robustness over noise-prone raw gradients for image-level feature attribution.

- Representation Analysis: Beyond per-example inspection, analysis of learned representations (via feature visualization, clustering, and SVCCA) exposes embedding spaces correlating with underlying scientific structure.

Figure 12: Direct optimization of input to maximally activate internal neurons, elucidating hierarchical feature extractors.

Figure 13: Clustering of Transformer representations reveals latent linguistic (and, by analogy, scientific) structures.

Advanced Methods: Generative Models and RL

The survey also annotates advanced models—generative models (GANs, VAEs, flows) for data simulation and manifold learning, and reinforcement learning for sequential decision-making—highlighting their specialized utility and implementation complexity.

Figure 14: High-fidelity human face synthesis with StyleGAN2, representative of state-of-the-art generative modeling capability.

Implementation and Best Practices

The survey distills a series of pragmatic recommendations:

- Prioritize data exploration and simple baselines.

- Leverage standard, modular codebases and pretrained models.

- Adopt systematic validation with independent test sets to diagnose overfitting and dataset bias.

- Analyze attribution and representation to safeguard against spurious correlations and latent biases.

Conclusion

This survey establishes a pragmatic and technically rigorous foundation for deploying deep learning in scientific research. While core supervised paradigms, robust architectures, and pretraining protocols are increasingly accessible to practitioners, the challenges of domain shift, interpretability, and data scarcity remain open. The continued synthesis of methods for efficient data usage, attribution analysis, and domain adaptation will shape the trajectory of deep learning’s impact on scientific discovery. The interleaving of methodological detail, scientific application, and community-developed resources positions this work as a foundational reference for accelerating translational advances across scientific domains.